What the remarkable success of the Grand Alliance in Bihar shows is that all secular forces have to be able to work together to defeat fascism in India

Excerpt from the second edition of the book published by Three Essays Collective

Fascism: Essays on Europe and India was published a little over a year before the fateful Lok Sabha elections of May 2014 which brought the BJP and its allies to power following an intense media campaign and blitzkrieg of election rallies, all dominated by the seemingly formidable and largely media-driven figure of Narendra Modi. Although the BJP polled only 31 per cent of the votes, the lowest ever of any party winning the Indian general elections, and its allies a further 7.5% per cent at best, the opposition to the BJP was badly fragmented. The 60%+ anti-BJP vote was thus widely dispersed and ineffective. The result of the Bihar assembly elections shows that this state of fragmentation is not an inevitable feature of parliamentary politics in India and can be tackled in the face of a fascist threat.

What has emerged in the eighteen months that the BJP has been in power is an increasingly overt assertion of the power of the RSS, whose proclaimed vision for India is to make it a Hindu state with or without the trappings of democracy. This is the first government of independent India where the RSS is openly in charge. Having gained power, it now seeks to expand its own power and entrench itself even further. In the long term the most dangerous aspect of this seizure of power will be the wholesale takeover of educational institutions, the rewriting of school and university textbooks, and the attempt to purge the Indian past of its non-Hindu, cosmopolitan strands.

The essays in this book that deal with India suggest that communal mobilisation is the ‘organic strategy’ of the RSS. This view has been vindicated by the way the present government’s parent (the RSS) and their sprawling network of Hindu organisations have been encouraged by the BJP’s victory and had the freedom to mount hate campaigns[1] that have led to a spate of lynchings and contributed decisively to the sort of political ‘climate’ where outfits operating in the shadow of the RSS can openly assassinate anti-superstition campaigners like Narendra Dabholkar.

Venom-spewing figures from the ruling party who have been conspicuous in these hate campaigns have had a field day in the past year and a half, since neither Modi nor other BJP leaders seem to care that hate speech is a crime and the hate campaigners in their ranks are openly stoking the flames of communal violence.

What has emerged in the eighteen months that the BJP has been in power is an increasingly overt assertion of the power of the RSS, whose proclaimed vision for India is to make it a Hindu state with or without the trappings of democracy. This is the first government of independent India where the RSS is openly in charge

The structured duplicity that characterises Modi’s regime reflects both the division of labour within the Sangh parivar between ‘state’ and ‘movement’, government and mass base, Modi and the RSS, but also repeated reminders to Modi about who he owes his position to and who ultimately calls the shots. The primacy of the RSS (as ‘movement’) has meant the emergence of a pattern of low-intensity communal warfare that may well spread to new parts of the country in a drive to communalise India. It is possible that before Modi’s term expires the RSS will have succeeded in transforming the Northeast into a new cauldron of communal violence unless the resistance to this is created from now.

Communal conflagrations are carefully organised episodes of violence and every round of ethnic cleansing drives Muslims and Christians into relief camps where they fester with no hope of ever returning to their villages. This pattern, driven by the RSS and its vision of an India where the minorities become second-class citizens, is creating legacies of hatred at the ground level that pile up like the blood-soaked debris of India’s failing democracy.

It is Modi’s silence about the recent spate of violence that has attracted most attention both from the ‘liberal’ media and from the government’s critics within the intelligentsia. India has just seen a remarkable groundswell of protest among writers, film makers, historians and scientists, and the government’s response, characteristically, has been to attack and vilify the protesters, denouncing them as ‘leftists’, ‘Communists’, agents of the Congress party and even agents of an ‘international conspiracy’ hatched to defame the country!

As if this infantilism was not enough, in a characteristic trope of fascist politics the aggressor emerges as the victim, Modi himself is said to be the object of ‘intolerance’, and every discourse about the growing climate of authoritarianism and hate politics in the country is converted into a sign of the illiberal nature of the opposition. ‘Liberal’ in the BJP’s lexicon seems to mean a willingness to submit to (be ‘tolerant’ of) a deeply authoritarian political culture, one that polices how we think, what we read or how we express ourselves and our eating habits as much it does the clothes women wear, one’s freedom of worship (or the freedom to reject all worship) and, crucially, sexual partnerships.

Meanwhile, in rally after rally across the state of Bihar [during the Assembly elections], Modi himself is scarcely ‘silent’, he fuels communal phobias with references to the ‘Darbhanga module’ (subtext: Bihar’s Muslims are terrorists, potentially) and to the incumbent chief minister of the state (who has now won a third term) having designs to deprive Dalits, Mahadalits and OBCs of reservations meant for them in favour of Muslims.

Wearing his election hat, the prime minister of the country has no compunction pitting one community against another on the basis of pure falsehood. This is the same political figure who, in his official avatar, is on his best behaviour as he interacts with world leaders like Obama (recall that he had mocked Obama unconscionably while campaigning in April 2009) and with royalty in Britain!

At another level, the past year has seen a gradual disenchantment with Modi and his government in business circles (key funders of Modi’s campaign), fuelled both by the BJP’s defeat on the Land Acquisition front and by the growing sense of a paralysis at the level of government. The leadership cult that was the BJP’s main strategy in the Lok Sabha elections has thrown up a style of governance (post election) characterised by massive centralisation of power in the hands of their ‘leader’ coupled with a serious lack of expertise at the level of the PMO; hence paralysis.

But resistance within the bureaucracy may well be a second factor. The economy was a major area of the campaign Modi had mounted in the months preceding the general election and this is where the sense of disquiet among his elite supporters has been most visible. At the end of July a major business daily could write: ‘India has…shown its steepest decline in a decade over the last year in AT Kearney's FDI confidence index, dropping out of the top 10 for the first time since 2002’ (Business Standard 29 July, 2015). Manufacturing remains sluggish, there has been no major inflow of foreign investment into manufacturing in spite of innumerable ‘summits’ and international trips.

For the present regime propaganda matters vastly more than policy, growth figures are reworked to sustain the illusion that India is actually doing well economically when the world economy is in recession and exports are falling, credit-rating agencies are lambasted if their warnings about growing ‘intolerance’ seem damaging to the country’s image (‘anti-national’), and domestic businesses realise that there is a charmed circle of industrialists who gain vastly more thanks to their closeness to the prime minister than most of them are ever likely to.[2]

More disturbingly, Modi’s government, driven by an extreme version of its one-sided commitment to capital (‘neo-liberalism’), is quietly engaged in dismantling even the minimal welfare provisions introduced by the two previous governments, witness the attempt currently underway to sabotage the functioning of MNREGA by withholding funds scheduled for wage payments under the scheme; or the slashing of the country’s public health budget from its appallingly low levels to an even more shocking one percent of GDP, which risks plunging India into major health disasters, even as pulses, a major protein source for the poor and middle class, become unaffordable for the mass of the population.

One aspect not taken up in these essays is the way what Wilhelm Reich called ‘organised mysticism’ is used to mobilise mass support for political figures like Modi. Reich used the term to refer to religious ideologies and their patriarchal-authoritarian hold over the masses. These themes are of pivotal importance to the nature of the emerging fascism in India, not least because of the light they throw on the repression and control of sexuality. Moreover, the spate of killings of rationalists starting with Dabholkar shows how deeply invested in these ideologies the right-wing in India remains.

The structured duplicity that characterises Modi’s regime reflects both the division of labour within the Sangh parivar between ‘state’ and ‘movement’, government and mass base, Modi and the RSS, but also repeated reminders to Modi about who he owes his position to and who ultimately calls the shots.

‘Godmen’ like Ramdev and Asaram Bapu are publicly associated with support for the BJP. Indeed, in Modi’s case a major role was played by the Hindu leader Asaram endorsing Modi’s political ambitions. In 2006 the then chief minister of Gujarat repeatedly invoked the ‘blessings’ (ashirvad) of this religious scamster whose ashram would soon become embroiled in scandals involving rape, murder and black magic, and who would himself be arrested a few years later on charges of sexually assaulting a minor.

It is hard to imagine any other major democracy in the world electing a prime minister with these past connections! Yet elected he has been, thanks to the role of the sangh parivar in building a ‘mass base’ through decades of molecular work (a labour of fascism) and deploying that base decisively for electoral purposes. As the preface and introductory essays in this book have shown, fascism only succeeds as a mass movement. ‘Ideology’ plays a major role in that process but ideology here has to be understood as a material force grounded in what Reich saw as the ‘psychic structures’ moulded from childhood by family, ‘tradition’ and the repression of sexuality in the young.[3] These are not aspects of fascism developed in the essays above but they deserve much more attention, especially in India.

A final word: there has been a lot of talk about the Congress Party reinventing itself to be able to recover its loss of ground. The same of course should be said of the Left parties which are now close to extinction as national parties. But parties can only reinvent themselves to the extent that they engage in a learning process. In the case of Congress today, it lacks any serious grassroots presence that can counter the mobilising thrust of the RSS. But it also has to confront the hard reality that much of the blame for the return of the BJP and for the current state of India’s democracy lies with earlier Congress regimes. As Kershaw said about the Nazis, fascism always taps ‘the rich vein of raw anger…opened up by the perceived failure of democracy amid mounting crisis’.[4]

In India this is obvious at three levels. The terrible culture of impunity that has allowed the BJP to get away with the Gujarat massacres is a direct legacy of the Congress leadership’s refusal to prosecute those within its ranks responsible for the horrific anti-Sikh violence of 1984. Failure to carry through prosecutions where they were due legitimised the use of mass violence as a means of political consolidation, a strategy that was fully exploited by the Sangh parivar. It is this that has created the bind that every time Gujarat 2002 is brought up the perpetrators are able to counter that with ‘1984’.

Again, successive Congress administrations showed a singular incapacity in dealing with hate speech and fascist mobilisations (they allowed the Shiv Sena to flourish in Maharashtra, allowed the demolition of Babri masjid, allowed the Bombay pogroms of 1992/3, and so on). Most spectacularly, UPA1 simply failed to make any effort to bring Modi to book on grounds of command responsibility for the violence of 2002.

Second, the culture of venality that grew up in UPA 2 in particular was a key factor in throwing the Indian middle class into the hands of the BJP. Even if much of the rage and rhetoric against corruption was artificially constructed by the absurd computational exercises of the CAG, the perception that Congress had allowed ministers and allies to get away with massive scams in coal and telecoms fuelled a surge of revulsion that played straight into the hands of the radical Right. Corruption, of course, is more deeply embedded in the bureaucracy than it is in the political class, but it remains the most powerful weapon parties can use to engineer each other’s downfall.

And finally, at the most basic level of all, the failure of the secular parties (the Communist parties included) to make any serious headway in confronting the backlogs of deprivation in the country (widespread malnutrition and landlessness, mounting unemployment and lack of access to public health being the chief among these), inequalities that are also largely related to caste but not confined to it, has provided fertile ground for the right-wing to exploit the accumulated underlying sense of deprivation and injustice.

This is of course equally true of the Left parties where they were in power at the state level, notably in West Bengal, and failed to build popular capacities. This backlog of failure is why ‘development’ has become such a powerful abstraction, one so effectively exploited by Modi, even if in practice he has a dilettantish fascination with new technologies and no conception of economic management beyond exhortations to capital (most often, foreign capital) to invest.

Having said this, it would be a mistake to write off the Congress either as a party without a future or as one irredeemably compromised by its failure to uphold secularism. What the remarkable success of the Grand Alliance in Bihar shows is that all secular forces have to be able to work together to defeat fascism in India. This includes the Left parties, which stayed outside that alliance and which, as noted, have never been closer to extinction as national parties than they are today.

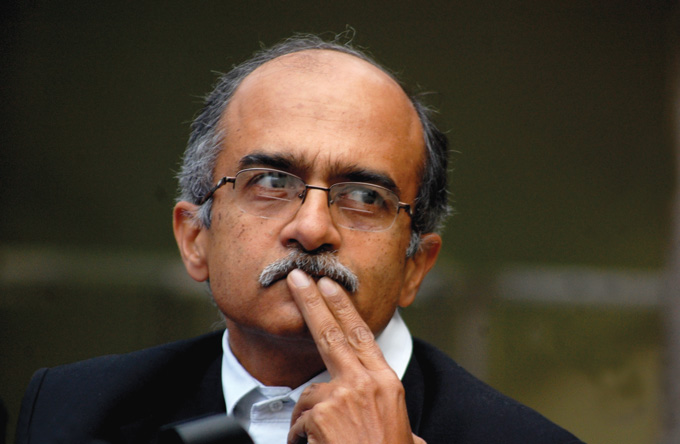

Jairus Banaji

8 November 2015

[1] The main ones have been ‘love jihad’, ghar wapsi (forced conversions), the beef ban, and scaremongering about Hindus being demographically drowned out by the minorities. UP and Karnataka have been bastions of much of this hate campaigning.

[2] An extraordinary public display of this partiality was the way the SBI chief was pressured into announcing a loan of $1 billion (the biggest ever for any private business) for one of the least viable projects thought up by any Indian industrial magnate, Gautam Adani’s Australian coal-mining project (in the Galilee Basin in Queensland) which none of the major international banks were willing to touch. It is inconceivable that the announcement would have been made without pressure from Modi. [4] Kershaw, Hitler, p. 332.