First published on: January 1, 2005

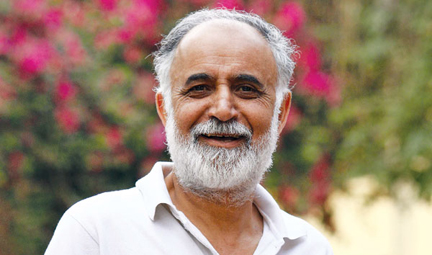

MK Raina is a well-known theatre director, actor and filmmaker, and a founder member of SAHMAT. In this account, recounted to Teesta Setalvad in 2005, he describes his rediscovery and re-engagement with his home in the Kashmir Valley and his determination to forego the fear and the anger so as to reclaim and preserve a precious multi-cultural heritage.

I have just returned to my home in Noida after watching a play at the National School of Drama’s national festival. It was a Kashmiri entry; a production of Waiting for Godot directed by one of my students and judged one of the six best plays at the festival. The play’s director, Arshad Mushtaq is from the Valley and the entire caste is from rural Kashmir. They come from a place called Gandarbal outside Srinagar, and most of them are Kashmir peasants.

This account is a glimpse of the whole story – Of what is happening there, bit by bit. It is also the story of my re-engagement with my birthplace, my home. My parents lived there right up to the tumultuous 1990s when events overtook the people and the place. I left Kashmir as a student to study in Delhi, at the NSD. I stayed on as a theatre person and director, making documentary films and working in theatre. My parents and some of my extended family still lived in Srinagar at the time.

It was in the summer of 1990 that my return to Kashmir began, painfully. My brother-in-law suddenly called to say that my mother had suffered a serious haemorrhage. I flew to Srinagar immediately and went straight to the hospital. Though I had been following the developments in Kashmir, it was during my drive to the hospital that the reality of what the Valley had become hit me. Things were bad, there was shooting and counter-shooting on the roads, even just outside the hospital.

For days the three of us siblings were stuck in the government hospital where my mother’s condition remained serious, she had sunk into a coma. No proper medical attention was possible as doctors were deserting the hospital due to the atmosphere of violence and intimidation. We were desperate to take her to Delhi but the one local doctor attending to her said that she was in too precarious a condition, she could not be moved for at least three weeks.

The next few days were an endless string of anxious hours of waiting. My brother, my sister and I took turns in attending to our mother, watching for the relaxation of curfews to rush home and return. We had no time for more than a few hurried words to ensure that the basics were being looked after, that my father at home was all right. There were no beds for us at the hospital. We stayed by her side, lying on the cement slab by her bed just to stretch our backs. Two weeks passed that way.

My father, poor man, was at home all through this period. And then, as sudden as the haemorrhage itself, my mother passed away in the hospital just as we, my brother, sister and I were making plans to take her to Delhi. I returned to hospital one evening, aur dar bhi lagta tha, it was frightening once the sun was down, expecting to sit with her when my brother said to me, "It’s all over. She has gone."

The next few hours were traumatic. There was no ambulance available. The few people around in the hospital and fellow patients were very good to us, very sympathetic. But the skeletal staff at the hospital was worried; the army had taken over. And we were told that we just could not take our mother home. I only remember this outburst of feeling, "Arre hamare shahar mein gaadi kaise nikalne nahin denge?!" (How can we not be allowed to take out a vehicle in our own city?)

That night was desperate. It was Friday, January 25, 1990. The army had taken over. All roads had been sealed. Shoot-at-sight orders were issued the next day. Then the Peerbhoys got some cars and helped us; we could never repay that debt. We didn’t even know which route the driver took, but he managed to get us home. We had to sit in the pitch-dark in our house that night with our mother’s body.

Come morning, we had to deal with the last rites. I do not know what had gripped me that day but I was determined to get a dignified cremation for my mother. This meant walking down deserted streets, lined with CRPF forces, eerie in their silence. I simply had to approach the authorities to request a cremation for my mother. As I walked down alone, scraps of memories from my activist past struck me, helped me. A friend and comrade, Bobby had once described how she’d survived in Poland… one of her graphic descriptions which probably saved my life that day. She told me that often when she’d needed to go out during curfew she always held her hands up above her head as she walked. I remembered what she had said and did just that. Just kept on walking with my hands up to appeal to someone to let us take my mother’s body for cremation.

My father was worried, he said, "It doesn’t matter. Let’s wait. We can have the funeral rites the day after…" But I was determined and very emotional about the cremation. The second person from the security forces I encountered hurled filthy abuse at me. I just kept on moving, with my hands up. All I felt was, "My mother needs and deserves a funeral and I will do anything to get that for her."

I remember one Jat, a Haryanvi officer who demanded to know whether I had any orders to move, to come out. I appealed to him, "Ma ki nidhi ke liye nikla hoon, agni lagaani hai Ma ko…" (We have to complete the last rites of our mother)… It made no difference. By this time I had reached a police station and a BSF commandant came out and asked me what the matter was.

I made the same appeal to him. As I was speaking to him I realised that we did not even know where to get the kafan (shroud) from. The commandant and another BSF officer helped us with the arrangements and got us to the Ganesh temple between the first and second bridge in Srinagar city. The temple doors were open, so we could go in and bathe my mother. My brother and I, along with two cousins and one Muslim friend who had insisted on coming with us. It was after this ritual was over that I actually looked around and saw the city. It was a chilling sight. Srinagar had been completely sealed off. It was a city I had never seen. "Yeh mera shahar nahin tha, jis galiyon mein hamne masti bawal kiya tha" (It was not the city of my birth where we had frolicked and made mischief).

It was through this eerie Srinagar that our procession wound its way after leaving the temple, trying to reach the cremation ground. In a city sealed off there are no ordinary people about, only uniformed army men at every step and around every corner. Every 40 feet or so, we had to lift the shroud and show our mother’s face to those who patrolled the streets. As we passed, there were loud sounds, a bomb was thrown and we heard an explosion at a spot somewhere behind us. What was happening to Kashmir?

Finally we made our way to the ground where my mother was then cremated. It was a Muslim who cremated her, that is the beauty of Kashmir… By the time we had arrived there I had no emotions left, I was numb.

Then, we did not know how to get back home. Normally, one never takes the arthi (ashes) home but that day we had to. The earthen pot containing our mother’s ashes was our passport to return home safely. I spotted the police headquarters at Batmalu. I stopped the truck we were driving and said, "Help us get home." After that it was one wireless message after another, stopping at checkpoint after checkpoint before we got home. There, my 70 odd-year-old father, my sister and two nephews were waiting anxiously. We were stuck at home for days after that. Even my mama and mausi (maternal uncle, aunt) learnt of my mother’s death only seven-eight days later.

I could never accept the fact that there was nothing for me in Kashmir. Even today I don’t have a home there. So what? Srinagar city was home! I was a Srinagar city bum, why couldn’t I go back to my city?

After this tragedy, we were faced with another dilemma. My father did not want to leave in such tragic circumstances, but he could not stay alone either. He talked to his neighbours at length, persons from the mohalla (neighbourhood), because we had been living there from my great grandfather’s time. There was a lot of pain in those conversations. Our dearest friends, our closest ones were helpless in the face of what was happening. Safety or comfort could not be assured. That is when my father left for Jammu. He never could go back.

From Jammu he came to our home in Noida. He was a fiercely independent man, as fit as a fiddle, he walked six kilometres every day. He used to be a National Conference party worker. He had his home, his dentist’s practice, his friends around the neighbourhood. My parents were very self-sufficient.

But once my father left Kashmir, he started suffering from hypertension. One day he told me, "I am too old." When he passed away some years later, my son Anto (Anant) remarked, "Baba did not go now. Baba had already gone." That is when I realised my son had grown up. He knew my father had never been the same after he left the Valley. Ever since 1990 our clan has been scattered. Some are in Jammu, some in East UP, others in Rajasthan, some in Pune. Our property is all gone. We had to sell it for a pittance a couple of years ago. Our children our grown now.

For me this period in 1990 worked as a catalyst. I could never accept the fact that there was nothing for me in Kashmir. Even today I don’t have a home there. So what? Srinagar city was home! I was a Srinagar city bum, why couldn’t I go back to my city? Soon I had the opportunity. In 1992, when I was working with Siddharth Kak on the North India section of the cultural television serial, Surabhi, we needed to shoot in Kashmir. I was the obvious choice for the unit since I knew every street in Srinagar. When our unit landed at the airport we were received by state security forces, there for our protection. The minute we arrived and security personnel joined us, I realised that we had made a mistake. I knew then that this was not the way I should have returned to my city. I went back to Delhi the very next day.

Then, about six years ago, I began the real journey back. Chances opened up through a PTI television series on Kashmir planned from a cultural perspective and without any propaganda. We depicted Kashmiris any and everywhere, inside and out of Kashmir.

When I first went back, I didn’t know where I would stay. There was Arshad (whose play is just being staged at NSD) whom I had met earlier. I had asked him to pick me up at the airport, not knowing whether he would come. He did. I still remember his smile when he greeted me! For 15 minutes, I couldn’t move… For 15 minutes my bag went round and round the conveyor belt. In those 15 minutes I made up my mind. I told myself, no security this time. I also remembered a little hotel with a kebab joint, Ruby Hotel on Lambert Lane. As I came out and Arshad greeted me I said we would stay at Ruby Hotel. "That’s it!" he said.

I also went to the Dastagir Sab shrine near downtown Srinagar. In days past, my mother used to give me Rs. 11 whenever I passed that shrine and she would say, "Ya Peer Dastagir, Allah theek karenge" (All will be well by the grace of Saint Dastagir and the Almighty Allah). I went there, offered Rs. 11, received sheere, you know, the round hard bits of sugar? I got five-six of those and then told Arshad that now we should start meeting people. We met writers, poets, hoteliers, businessmen and many others. I was lucky we were moving around fearlessly.

Then some years later I began a project filming heritage sights in Kashmir. The day my father died I had a nightmare that frightened me… All the beautiful shrines of the Valley, all my childhood images would one day just disappear. I didn’t want the Shah Hanadan shrine, its beautiful architecture, to just disappear. My mausi lived opposite Shah Hanadan. Whenever we visited her we would bow our heads low in respect to the shrine. As children we were told a story. That Shah Hanadan and our other beautiful structures were all made from one forest of wood each. Imagine if they all disappeared! I had this fear that they might go. Charar-e-Sharief had been gutted in 1995. In 1996, on one visit, I remember calling my wife Anju and telling her that I wanted to record these heritage sites so at least our children, the younger ones who had never seen Kashmir, could soak in this heritage. She was very supportive. As I began shooting, temples, mosques, dargahs, my own fear dissolved. The only condition my family insisted on was that I should phone them every evening.

While I was shooting, the evenings would depress me because then the shroud fell on Srinagar. Everything stopped moving. Curfew was on. The Residency on Lambert Lane used to be the hub of activity. There was a coffee-house there. It served a lousy cup of coffee but it was the cultural hub of Srinagar, the spot where all the great intellectuals of Kashmir, from the world of literature, song, theatre and poetry, met. Now not a soul could be seen as evening fell. One evening, some time in 1997-1998, I found myself in tears for there were no faces at the coffee-house to remember.

In Delhi, NSD and theatre was my life. Around this time, someone suggested that I do a play on Chhattisgarh. Why Chhattisgarh, I remember demanding. I said I wanted to do a play on Kashmir. This began another journey back to the Valley.

During my earlier stays in the Valley, shooting for films and documentaries, I had re-established contact with many old colleagues. One of them, Shafi saab had through INTACH already conceived of CHECK (Centre for Kashmiri heritage and environment). We decided on an official collaboration through an NSD workshop in Srinagar. We, Shafi Pandit and I met senior bureaucrats to solicit space for 30 people to live and have a residential theatre workshop. Finally, we were given space at the agricultural university, Sher-e-Kashmir. The registrar was wonderful; he had seen me on television and showed me a beautiful bungalow, with a forest as backdrop. An empty hostel would provide the rooms. It was just the place I wanted.

I advertised for participants in the local papers. I received no responses on the first day. One evening, two days later, a student from Baramullah came. Within seven days, I had students from Sopore, and Gandarbal as well. This was what they needed. Young people needed this space for expression. A residential workshop of this kind gave them a welcome release from the lives they led, or had been forced to lead.

The workshop was completely self-sufficient and Gandhian in principle. It was cook, clean and work. It was a very tiny place but set in lovely surroundings. A garden in an apple orchard scattered with chinar trees. The workshop lasted four full weeks. We performed theatre, saw several films on video and invited Kashmiri intellectuals for discussions at specific workshops.

That experience remains the foundation of what I am still trying to do in Kashmir. It was a small beginning. You know, to climb on to a horse and ride you first need the four-legged structure to get onto the horse in the first place? For that you have to build that structure. We are trying to do that so that we can begin climbing on to the horse.

I was 18 when I left Kashmir. When I returned in 1990 when my mother died, I was married with two children. There was much to learn about the years in between. I can only say that now, with this first workshop, the bottle has been uncorked.

I am not a hero. We do not need heroes. We need ordinary people who act as catalysts to re-start the normal everyday processes of living, healing and forgiving. My deepest regret about Kashmir and the state of affairs there is the utter failure of Indian civil society when there was a crisis at hand. I am active in the anti-communal movement and often felt frustrated and alienated when there was little or no attempt by radical activists to relate to the ongoing crisis in Kashmir.

A cultural awakening is a must for a genuine resurgence of health and vigour in Kashmir. You know the education of the Kashmiris has been ruined? They have forgone their rich heritage by dumping the Kashmiri language and have adopted a very inferior kind of Urdu. It was and is my endeavour to bring the Kashmiri component of culture to these children of the Valley. Along with the cream of Kashmiri intellectuals, we spoke of the richness of Kashmiri culture to the young. Rehman Rahi, the renowned Kashmiri poet, spoke to them on what Kashmir was before Islam; he spoke of the Buddhist influence on Kashmir, the influence of Shaivite Hinduism on the Valley. The Kashmiri Pandit scholar, Ganjoo saab, who knows the old Kashmiri script, spoke of the evolution of the language. We had Abhinav Gupta, a scholar of Sanskrit, giving his commentary on Natya Shastra. The whole impetus was to communicate to the young what you are, what have Kashmiris made of this land? They were told Kashmiri short stories, wonderful stories. If I can ever raise the resources I will make a film on one of these stories… they beat even Kafka in their craft and depth.

I am not a hero. We do not need heroes. We need ordinary people who act as catalysts to re-start the normal everyday processes of living, healing and forgiving

We developed performances and also put up an exhibition of our paperwork. At the end, we performed to an audience. Five years ago, after God alone knows how many years, there was a public performance at the Tagore Theatre. This whole cultural experiment with residential theatre workshops set the pace and with every workshop we found more people. Soon we were running short of space at the first location.

In the second year, we performed a play with new people. By the third workshop the university had run out of space, so we moved our workshop to an indoor stadium near the Passport Office (which incidentally was attacked in early 2005) and held our rehearsals there. This time, instead of directing the plays myself, I told Arshad and Hakim Javed to do so. We had a two-day festival at the end of the workshop. Today they are making their directorial debut at the NSD in Delhi!

There is much insularity within Jammu and Kashmir, be it in Ladakh, Jammu or the Valley. I believe this insularity needs to be addressed. One way to do this is through cultural resurgence. The work is like aachar lagaana (making pickles). You have to work at it for a long time before the end product results. Slowly you can earn trust. I know they are my own people. I have to win them back.

My daughter Aditi accompanied me on one of my trips back. She was studying the impact of violence on children. She insisted on moving around on her own, visiting schools, orphanages and interacting with local activists. On a visit to the Chashmeshahi Lake she witnessed the humiliation that Arshad and Javed had to suffer when they were stopped and searched by security forces. I used to insist that things were normal in my Kashmir. She turned and said to me, "How can you say things are normal? There is fear and terror." My own child opened my eyes to another dimension of the tragedy. Children.

The Rajiv Gandhi Foundation gave me a small grant to work with children whose lives had become a living hell. There was no education worth the name, either. As a result, we had a residential camp in Jammu in February last year. Srinagar kids were brought to Jammu camps. There were 40 kids from Srinagar and 15 from Jammu. Both groups had seen violence. They were like tense little birds; these were children who had seen trauma. They wanted to avoid contact. Many mothers volunteered at the residential camp. We spent 12 days at the camp together.

I had each child’s case history with me. There was anxiety and concern about the experiment. What would 12 days out of their homes mean? There would be Hindus and Muslims staying together? Would this cause more pain than healing?

We proved the sceptics wrong. Nothing untoward happened. If any child was upset, he or she went to one of the ‘aunties’ who were organisers as well. These aunties were also mothers. The children stayed awake late into the night, sharing experiences, whispering fears. Kids moved into one another’s rooms. They held hands, slowly. The division crumbled… As the camp came to an end they all howled for an hour because they had to leave.

Suddenly they had all become part of a larger family. Last year the same children attended the camp again and some new children also joined. These included migrant children. Camp mothers of migrant Pandit children came to Srinagar. We had to keep a daroga, a watchman, since we were near the lake, but it was a tremendous experience.

There are just so many stories. One woman, Usha took us to her home or what had once been her home. Initially, she didn’t want to go to her home near Pahalgam, she couldn’t handle it. When we visited the temple complex at Pahalgam, however, she began to get restless. As we approached her home, "Mera ghar peeche rah jayega," that’s my home, she said. Then, when she finally did go, she found her home intact, her mohalla intact. She met persons from the neighbourhood. Though she was torn when we left, I saw a different face now. Usha’s face held less fear. More confidence.

The year before last, I took Sanjay, a Pandit from a village, back with me. He works in film and television as a freelancer in Delhi. When we reached Srinagar, he was frightened, paranoid. Red in the face, he sensed a policewoman staring at him. She turned out to be an old classmate who came up to him, "Tu Sanjay hai na?" (You are Sanjay, right?) They were meeting after 12 or 14 years. She insisted that Sanjay go to her house and meet her husband and children.

He was very tense on the streets of Srinagar. Arshad and I, and the others took Sanjay to Lal Chowk and other familiar haunts. We felt that we all had something precious that we needed to fight to reclaim and preserve. As we took him around Srinagar, we reached the Cheel Bhawani temple, 20 km away, which we were also filming. As we neared the temple, he became more and more tense. The symbol of his faith in his homeland was bringing back all kinds of memories. I told Arshad to take special care of him. Inside the temple premises it was as if a chain inside him had snapped. He started sobbing like a baby. Arshad hugged him and took him to the bench. They sat there talking and talking and talking… I just thought, "Yeh Bharat milan ho raha hai" (This is meeting, Indian-style).

And then do you know what we did? We asked him if he wanted to do a puja and he said yes. We then went outside to the man selling earthen lamps. In Kashmir, he too is a Muslim. Despite years of violence, this Muslim was there and he had kept the tradition alive. His name was Ghulam Mohammed, a poor peasant. We asked him how many diyas he had; he had 80 or 81. We bought every single one of them, lit them all. Then we performed the aarti for Sanjay as bhajans were sung in the Cheel Bhawani temple, Sanjay, Arshad, Javed and I. Then we ate the prashad (offering), tears flowing down our cheeks. This was Sanjay’s therapy. Sanjay continues to go back to Kashmir today. He is now going back to shoot a story of an ex terrorist who used to be his classmate…

Who can understand this reality? Ek Kashmiri Pandit ki puja hi nahin ho sakti jab tak mitti ke bartan – joh Mussalman banata hai —woh na ho. (A Kashmiri Pandit’s prayer ceremony is impossible if the earthen vessels – made by a Muslim – aren’t there.) My father used to say Janm se marne tak Mussalman ka saath hai, from birth to death, Muslims are with us. We have to re-build a future on this rich tradition of multi-culturalism.

I now have 150 friends in Kashmir from the world of theatre. Twenty are in Delhi performing right now. For me, I know that my Kashmir is there.

Initially, when I started going back I was, for them, a strange nut. But after my experience in 1990, I was sure of two things. Fear feeds more fear and anger fuels more anger. But if you hold out your hand then the fear and anger dissolve and the healing begins. By God’s grace that has happened with me.

(As narrated to Teesta Setalvad).

Archived from Communalism Combat, January 2005 Year 11 No.104, Cover Story 2

.jpg)