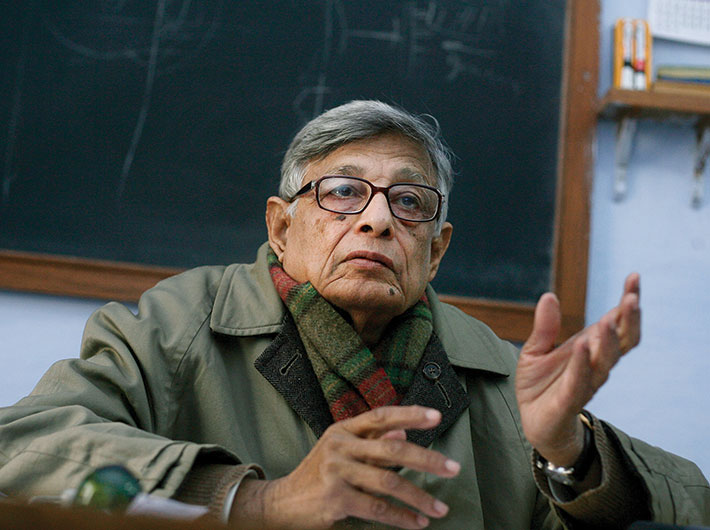

Courtesy: Arun Kumar / governancenow.com

Professor Mushirul Hasan, members of Sahmat, organisers and management of India International Centre, ladies and gentlemen, it is a very great privilege to have been asked to initiate the series commemorating one of the greatest sons of India. at the same time I am more than a little nervous that Professor Mushirul Hasan is presiding over the function because this is debatable whether I am great or not but I mix up my dates awfully, so I will try to be very careful about them hopefully.

I should begin by making an assertion which is seldom made that the Indian National movement is the greatest creation so far of the Indian people. This may or may not be debated by the Indian national movement is a phenomenon in our history, unique, can hardly be questioned. These days it is becoming very common to run down the concept of nation. The Cambridge school had told us that in India, family and caste are the basic units and not anything else, all other things are illusionary.

Benedict Anderson in his Imagined Communities thought that nation was just an imagined community created by print media. And Perry Anderson in his recent book, his elder brother, Indian ideology 2012, which in a review I thought should have been called Indian Illusions, says that the Indian National Movement was not necessary at all, a statement that even Cambridge scholars had not made, that the act of 1935 and Japanese military successes were sufficient. It is therefore important first to see what the national movement was about and then to see in the present occasion why Jawaharlal Nehru’s intervention and leadership was so crucially important.

Now what the Cambridge School and the Andersons forget is that one of the major factors behind the creations of nations all over the world, in most cases conversions of countries into nations has been the phenomenon of colonial and imperialist exploitation. India was long regarded as a country, there is no dispute about that, but that it was a nation before the 19th century will be doubted. As Ram Mohan Roy had said, Indians are not patriotic; their basic affiliations are to their caste, 1828.

So what happened and why and how did this turnaround come? One of the major reasons for this was the work, as Pandit Nehru realised and indeed celebrated, the work of early nationalist, economist Dadabhai Naoroji, the grand old man of India, Ramesh Chandra Dutt, Subramaniam Iyer, Deoskar, Justice Ranade and others. They told us, they explored what the Indian poor could never have done for themselves, how Britain was living tribute on India and how hatred was causing de-industrialisation. Whatever the subalterns may say, these discoveries could not have come out of subaltern efforts. By 1905, as Professor Bipin Chandra in his classic work, the Rise and growth of Indian Economic Nationalism, points out the total picture of England’s exploitation of India in the writings of these moderates was complete.

Even today one might mention that if you take Sivasubramaniam’s National Income of India statistics, the major effort so far, then the per capita income of India between 1900 and 1947 rose by dramatic percentage 0.2% or less, 0.2% per annum. If between 1946-47 and 1990-91 under free India, the growth was not very spectacular, yet it was sensational compared to what happened under British rule in 47 years. It now amounted to 1.1%, five times the per capita growth attained under British Raj and complete conditions of free trade which now all the good newspapers in India want us to go over to.

What happened in the next stage that one would call roughly, after 1905 particularly after the partition of Bengal and notably after the arrival of Mahatma Gandhi in 1915, he left south Africa in 1914, was that the message increasingly got across to the Indian poor and one of the channels through which it got across was Gandhi and his followers. In Hind Swaraj in 1909, Gandhi argued that religion has nothing to do with a nation, that Indian and India, therefore people of all religions should live in amity and he summarized the picture that the nationalists had drawn of British exploitation of India, an adequate and capable summary.

The second thing which Gandhi did on which his experience of south Africa counted so much and above all his own personality was to link the national movement to the agitations for the rectifications of the grievances of the poor. Not mere pamphlets, not mere articles in journals and books but actual agitation. To that extent, in that sense, the Champaran Satyagraha of 1917, the subsequent Kheda Satyagraha of Gujarat peasants and the textile workers strike of 1918 were outstanding events. Now one need not recount the spread of the national movement immediately after these agitations, notably the April Satyagraha against Rowlatt Act of 1919. And then the Khilafat and non-cooperation movement of 1920-22. These were unprecedented in the number of masses brought into the movement.

Here however a point of crisis was reached and I think this is a point of crisis which must be understood, why it was reached. Gandhiji had brought about a revolution. There is an Urdu verse which I have often quoted, so I ask the forgiveness of people who have heard me quote it before. Akbar Allahabadi’s verse, Buddhu miyan bhi hazrat e Gandhi ke saath hain, e musht e khakh hain magar aandhi ke saath hain. Buddhu Miyan didn’t come before, he countered but what for? If we now turn to Hind Swaraj, we see a problem there. Gandhi is against British rule. He knows how India is being exploited by England. Dadabhai Naoroji and Ramesh Dutt have told him, Gokhale his mentor had told him. But when you come to the solution, what is the solution there. not even social reform. Not even a denunciation of the caste system, of untouchability, not even a declaration of women’s rights in Hind Swaraj, a minimal state, all left to self-help.

Characteristically I forget the date but when he came to AMU for the first time, the lecture he gave was on such an uninviting topic as self-help. Indians were to overthrow British rule and after their liberation live by self-help, minimal state. He thought that was the kind of state which the rajas and baadshahs has ruled with the support of pundits and maulvis. To many of us this would look like an awful idea but he thought that this was the ideal that India should look to. In other words Gandhiji was all the time appealing to people for self-correction, to landlords to be good custodians, establish schools and hospitals for their peasants. Similarly capitalists were to be good custodians, the state will have nothing to do with all these things, perhaps a minimum of law and order. And since he believed in non-violence, a minimum of the army. Could this make an appeal to… he had moved the middle classes like never before on Rowlatt Acts, he had moved a larger mass on the issue of Khilafat and Punjab wrongs but all the time you see hesitation in Gandhiji in demanding independence. Curiously he was very much a constitutionalist like the moderates.

In 1919 December even after Amritsar, he was counselling that we should rework the reforms without carping criticism, the 1919 government of India Act reforms.

By 1905, as Professor Bipin Chandra in his classic work, the Rise and growth of Indian Economic Nationalism, points out the total picture of England’s exploitation of India in the writings of these moderates was complete

The breakdown of the Khilafat movement, its withdrawal in early 1922 brought the crisis up. Atleast CR Das said he wanted an Indian state for the 98%. But Gandhi did not want a state at all in effect. He wanted a minimal state. And so behind the issue of individual non-cooperation or limited cooperation in which the Swarajists and Gandhians fought was this issue lurking behind what kind of India.

The second difficulty with Gandhiji was what Nehru called his metaphysics, his lack of rational approach, his declarations in the nature of arbitrary diktat rather than reasoned arguments. Throughout Hind Swaraj there is no celebration of reason and rationalism, there is only celebration of religion.

This to my mind is the reason why Jawaharlal Nehru had that particular mental crisis of which is major biographer, Sarvapalli Gopal, speaks. Although he does not relate them to these two issues but rather to his personal relations with Motilal Nehru, the Swarajist leader, his own father and Gandhiji on the other hand. They were at opposing sides and Jawaharlal Nehru supported Gandhiji against his own father. Motilal Nehru said bitterly to Jawaharlal that you want to live without working as a non-co-operator all the time expecting me to demand higher and higher fees so that I should support you.

So obviously these issues were there but behind these individual problems were this particular problem which perhaps one can only see by way of hindsight. At that time they were probably not clear. And so Nehru went to Europe. And again, I am not saying anything radical, that is what Gopal has said, this brought about a total change in his outlook. He came into association with people resisting colonialism throughout the world. The Brussels congress was particularly important. He went to soviet Russia and had his first glimpse of socialism which he undoubtedly studied critically but which still made a great appeal to him because he heard things in Russia about the equality and resistance to class exploitation which he had not heard elsewhere. In both Glimpses of World History and his autobiography he makes statements that to him, Lenin and Gandhi were the greatest leaders of the poor in his century.

When he comes back there is a sudden shift in the national movement, not at all realized by Nehru himself. Everyone thought that the Madras Congress Resolution for total independence in 1927 was an aberration. But why did it get passed at Nehru’s and Subhas Bose’s insistence. It got passed because there was a sickness in the national movement about the lack of radicalism in congress demands. Behind that, behind the moderation of the leadership was the anxiety that the congress should say something which should make or appeal to the mass of the population.

And I think here Nehru’s greatest contributions come. He wrote, as you know, two major works in this period, the period of civil disobedience and its aftermath, civil disobedience lasted from 1930 in the first phase to 1931 and he was in prison and then he again went back to prison. And Jawaharlal Nehru wrote Glimpses of World History for his daughter which was published in, if I am not mistaken, 1934 and then subsequently the autobiography published three years later. In both these works which were written in prison, Nehru makes certain points which are extremely important and which demarcate him from Mahatma Gandhi’s positions very sharply.

The first point is his celebration of reason. In Glimpses of World History what is remarkable is that although religions are described, they take a very secondary place. he is not prepared to accept at that time that religion contributed anything positive to humanity because that ends reason. And incidentally another colleague of his whom you would not think of asking such an embarrassing question, Abul Kalam Azad in 1907 asked the same question, Has religion done anything good to humanity? His major complaint against religion was it deadens reason and it makes the human being servile to the illusion of an afterlife. Both in his glimpses of world history and autobiography, he proclaimed his indifference even to Hinduism and Hindu practices and also to the concept of God and regarded this as an unnecessary concept.

In Glimpses of World History he picked a very important statement of the Jesuit fathers about Akbar. The statement was, Thus we see in this prince Akbar the common fault of an atheist who refuses to make reason subservient to faith. Now that Nehru should pick this out in order to commend Akbar and that he should add, if this is a definition of an atheist, the more we have of them, the better. Similar statements occur in autobiography.

I have often wondered at the curious shiftiness of the Indian people. Then when Nehru said all that, they celebrated him, they idolized him. What has changed in these two generations that the reverse is the case today. In any case here he was in total conflict with Gandhiji whom he regarded as his master. He said in autobiography that Gandhiji’s dangerous affiliation to metaphysics and to his declarations of policies and statements without reason makes it very difficult for the national movement. He describes Gandhiji’s immediate followers as people who had been reduced to mental pulp, thoughtless fellows.

That brings me to another wonderful thing, that Nehru should say all this and Gandhi should still declare him his heir. One feels that one is talking of some other country. The second important thing that Nehru brought in was what he thought was socialism but indeed he did distinguish also between a welfare state and a socialist state.

The second important thing was the difference on the role of the state. Pandit Nehru was I think in communist language sectarian when he declared that the communists were wrong in thinking that the national movement can be directed towards a proletarian and pro-peasant movement. The very idea of nation he said is bourgeois, a statement that even Stalin didn’t make. He said, the national question is a peasant question. not necessarily a correct judgment but still a better judgement perhaps that Nehru’s bourgeois nation. And since Indian National Congress is a national organization, it is a movement to build a nation, it must be a bourgeois party. the concept that the congress or national movement can be a multiclass movement had not even developed within the communist movement at that time. that was largely left to the Dutt-Bradley thesis of 1936 but that is another question. I say that because Nehru was very familiar with communist opinions and he in fact says that on many matters what the communists have said have proved correct and they have been very insightful. This does not mean however that he agreed with them on other matters. However the main issue was that the congress should present in Nehru’s mind a picture of what India would be when it is independent. A picture that would be totally different from Hind Swaraj which would not appeal to the Indian people. They didn’t want a minimal state, they wanted a supportive, they wanted a democratic, they wanted a welfare state at the least. And here there was a major issue between the two. This lasted till the last days of Gandhiji.

The second thing which Gandhi did on which his experience of South Africa counted so much and above all his own personality was to link the national movement to the agitations for the rectifications of the grievances of the poor.

In 1945 Gandhiji wrote to Nehru, I have said that I will stand by the system of government envisaged in Hind Swaraj, the village of my dreams is still in my mind. Nehru replies in astonishment that he should think of a state in India in such a way and believe in what he said almost 36 years ago in Hind Swaraj. Gandhiji, in fact, in practice set up Mashruwala to write against rationing and promoted this article in Harijan and also in his statements that there should be no rationing which would have meant in practice the death of a large number of poor people just because he hated state intervention in these matters. So there was a total difference of opinion.

And here therefore comes the second intervention, the first intervention is a celebration of reason in the national movement, a celebration of rationalism, and the second important element and that was the welfare state. Unfortunately because of Nehru’s innate modesty he does not celebrate the Karachi resolution of 1931 in his autobiography. He says these things could be done by any capitalist state, they had not been done by any capitalist state till that time, later also post-second world war years, but not in 1935. This fundamental rights resolution after the discontinuance of the civil disobedience movement in 1931 as modified and in fact strengthened by the all-India congress committee in august 1931 lays down many fundamental things about India including the secular state about which I shall have soon something to say. It for the first time proclaimed the equality of men and women which Gandhiji had not until then and certainly not in Hind Swaraj ever recognized. Later on, yes, but even then he would not recognize equality, he would say women are superior to men, they should be generals because they are compassionate whereas men are cruel and idiots. He could say that and get away with it but the concept of equality, the modern concepts of equality had passed Gandhiji by.

This resolution says, no disability. You know this is what the picture would be of India when it is free, no disability attaches to any citizen by reasons of his or her religion, caste, creed or sex in regard to public employment, office of power or honour and in the exercise of any trade or calling, totally against Hind Swaraj. And labour protection, women protection, all that is there but then also land to the tiller which Gandhiji had until then opposed and was to oppose even later.

The system of land tenure and revenue and rent shall be reformed and an equitable adjustment made of the burden on agricultural land immediately giving relief to the smaller peasantry by substantial reduction of agricultural rent and revenue now paid by them etcetera etcetera.

Then come to Clause 15, the state shall own or control key industries and services, mineral resources, railways, waterways, shipping and other means of public transport. Public sector, control of industry anathema to Gandhiji.

Now the Karachi Resolution was made the basis of the election manifesto of the Congress in 1937 and it had astonishing success. It was again made the basis of the election manifesto in 1940 for 1946 elections. No one can say that these were hidden. Gandhiji had actually moved the resolution and he had added one particular para to strengthen it, Relief of agricultural indebtedness and control of usury, direct and indirect, are in his hand writing.

The state shall provide for military training of citizens, totally against Gandhiji’s philosophy. This is a picture that Nehru’s draft presented to the Indian people and even Gandhiji realized, I think, in his heart of hearts that the Swaraj type of state would make no appeal to the Indian peasant and labour.

The third matter that flows from it and that actually flows from both, the concept of supremacy of reason and the concept of a welfare state is the secular state. Nehru had the international notion of secularism and it is important to know what the worldwide view of secularism is and not the view of this Indian Supreme Court. The worldwide view of secularism is that the state is bound to take all efforts of welfare, human welfare, which are only in terms of the material and spiritual comforts of those people in this world. anything done because that would bring reward in afterlife is anathema to secularism. In fact, Holyoake who first used secularism was looking for a definition of a philosophy of morality in which afterlife won’t count, religion won’t count. It is no business of the state to ensure that Muslims should pray five times a day although that may lead them to heaven but this is no business of the state. Or that Hindus should perform pilgrimages is their personal matter, for their being born better in afterlife that is no business of the state.

This is Nehru’s position throughout. He is one of the few Indian leaders who used the word secular in 1930s and 40s. In fact, the word secular therefore did not appear in the Constitution at all, it was added in 1976 through an amendment to the preamble.

The ground has been infinitely muddied by that doubtful philosopher Sir Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan. In his book, Recovery of Faith, he says, when India is said to be a secular state, not France or England but India, it does not mean that we reject the reality of an unseen spirit. If the spirit is unseen, how do you know it is real. So the very formula is ridiculous. Or the relevance of religion to life which is totally against the philosophy of Holyoake, the French revolution and human secular values throughout the world.

We hold that not one religion should be given preferential status. And on the basis of this kind of nonsense, the Supreme Court went further and made a statement of absolute fantasy that all the great values in this world have come from sants and saints which gave us democracy, equality of women and men, socialist values and so forth. But this is the law of the land today. And when the constitution prohibits religious instruction, the Supreme Court allows instruction in religion in government institutions.

Now clearly it was Nehru’s position and not the position of others who believed in a kind of religiously tolerant state that strengthened the national movement and gave it an argument against the Muslim league and other splinter parties. Nehru, in fact, argued in his autobiography that whereas Muslim separatism can be identified as such because they are in a minority, Hindu communalism masquerades as Indian nationalism. I doubt if they even masqueraded. I doubt very much that they even masqueraded. RSS has no record of any agitation against the British government.

Here if you permit me I shall bring to your notice a joke from Pakistan. In Dawn recently or about six months ago and that article was published in the journal of Pakistani Historical Society, so I came to know of it and published without any challenging note and that was that there is a psychological problem in Pakistan. The problem in Pakistan is that the whole national movement of Pakistan was not dead against a ruling power but against fellow subjects. We had nothing, no quarrel with the British who governed the areas that are Pakistan, our only quarrel was with Hindus. The same applies also to RSS and Hindu Mahasabha, they had no quarrel with the British, they had only quarrel with their Muslim fellow subjects. So before we laugh at the joke in Pakistan, we should consider that we have just elected a government whose entire national credentials are anti-Muslim credentials.

Well, coming back to the importance of secularism, this a very great misfortune that a debate in 1940s did not occur and it did not occur because of the Quit India Movement when for three years all congress publications were closed, students had been put in jail and therefore Muslim League propaganda had an open field. So Nehru’s secularism never had the chance.

This brings me now to 40s and here I am afraid I must take issue with what Pandit Nehru did in the 40s. when the war broke out between two bits of colonial or aspiring colonial power groups, the congress took the position that the Nazis are the worst side and they should therefore be opposed but an agitation against the government should continue. The agitation was to be individual satyagraha so that the government is not embarrassed. When in 1941 and 1942 the pendulum swung on the other side, there was the Nazi attack on the Soviet Union and there was a very powerful Japanese offensive not only against Kuomintang China but then in Southeast Asia, occupation of Burma and so forth, Gandhiji’s position changes. For a man of moral authority this is an astonishing change. He believed, as many said, as Pandit Nehru himself said, and as Sarvapalli Gopal considers to be the case in his biography of Nehru, he believed that Russia and China would be defeated. He did not play much attention to the German defeat before Moscow. He believed in the Nazi propaganda that the Germans were about to cross the Volga near Stalingrad. Similarly he thought and he wrote in fact that Japan had no intentions against India. How did he know? That if therefore, now was the time to agitate when the allies were at their weakest, then the British could be made to yield but they had not yielded through Kripps Mission. And therefore Gandhiji began through his supporters even before anything was decided by the Congress to develop a movement towards civil disobedience. Nehru speaks in his Discovery of India 1945, of the continuous increase in excitement which Gandhiji’s statement made.

In 1947 both Gandhiji’s and Nehru’s dreams united as never before. Both wanted that communal slaughter should stop, both wanted that even if division came Muslims should live in India and Hindus and Sikhs should live in Pakistan. They both felt that their primary duty was to do their duty in India

Here what is not very relevant is still a joke from 1942. After his rejection of Kripps Mission, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru began touring, as was his wont, he was a man of action and he didn’t tour only for elections, he toured to build a party. he came to Aligarh. Characteristically his hosts forgot that being a human being he needs lunch. They took him from place to place and every time said lunch, but we were never told about your lunch. And so he got very annoyed and he said that I know a person called Professor Habib, you take me there. And so around 3.30 when we were playing, my elder brother and I, in the garden, we found Nehru arriving by Tonga, getting down, breaking into house, practically shouting Habib, Habib, make me an omelette and as we hid behind doors and as he consumed the omelette, my father told him, Panditji, why did you reject the Kripps Mission, we had atleast hope of being a dominion. And we watched Nehru looking scornfully at my father, saying, Habib, just remain professor, within five years this country will be free. And it took five and a half years, he was wrong by six months. I remember the incident and this tells you something of the man. I don’t know whether he did in fact want to reject the Kripps Mission proposals but he certainly was very loyal to that decision.

But was he loyal to his views subsequently. How could anyone then attack the British government and agitate against the British government, launch a civil disobedience which only would benefit the axis powers. And then not only that but making statements, running down the world, he says in a quotation from Pandit Nehru himself in his Discovery of India and he gives this quotation and I have again a grouse against Pandit Nehru that he should have selected this quotation, in which he says, we must learn, Gandhiji said on 8th August, we must learn to look calmly at a world which has blood thirsty eyes at this time.

What was this world? Russians and Chinese defending their homeland or Nazis and Japanese generals strutting over the subject countries. the world has done us no harm, so why should we look calmly and scorn at the world. and why should Jawaharlal Nehru have quoted it, quoted it sympathetically. In his Discovery of India, he concedes that nationalism triumphed over internationalism in the Quit India Resolution. But why then Sir did you support it? Why then did Abul kalam Azad support it? It was a kind of blackmail that you would be then condemned as people who were not brave enough to face British rule but was this enough reason. Were you not being metaphysical like your critics. I think that that was a very great error. To my mind it was not only immoral to do that at that time, to do it for opportunistic reasons but it was also an ideologically very wrong step. And one of the results was that, in fact, congress was wiped out in Muslim localities. It had no Urdu paper, it had no support left. Its all newspapers or publications were banned, its offices closed, its ordinary workers put in prison.

This brings me to the apologia that is Discovery of India for Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru’s conduct. I feel with Gopal that Discovery of India in quality is very inferior to his two worldly books. That is Gopal’s judgement. But then more than fall in quality, the statements he makes, we are proud of the achievements of our race, the past achievements of our race. Race? Are you a Nazi? You had said that nation is a bourgeois idea. So India comes into focus, let other countries suffer, India is my particular, I have discovered India. the history is also despite its great insights, very dangerously tilted. I have already mentioned Sir Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan, that a knight obtaining knighthood from the British government, the most obviously foreign rulers should tell us that Indian philosophical thought languished because of foreign rulers from Greeks, Shakas, Kushanas, Muslims, not of course British but all these foreign rulers and that Nehru should accept it. He only changes it, yes, we were great thinkers in the past as if he had never heard of Shankaracharya in the 9th century, he had never heard of other thinkers, he had never heard of Abul Fazl. We had great thinkers in the past but it was not foreign rulers by acts of which we fell. We became imitative and so lost our creativity.

If you look at history, a country which does imitate never creates. Europe became, as in Glimpses of World History, he himself pointed out, because it imitated Chinese inventions and Arab science.

Now all that is past. There is an Indian nationalism which is totally rational. I have said again that there are great merits in the book and those merits of course remain. They still are a very good treatment of Muslim political movements. There is a very good treatment and an honest treatment even of the events that led to the Quit India Movement. Nevertheless, now we hear Nehru saying, “Religions have contributed a lot to the good of humanity.” The ideas of Glimpses of world History, the ideas of Autobiography are forgotten. Even religion is exalted.

So I did think that if Nehru solved the crisis of nationalism without knowing that he was solving it in late 1920s and early 1930s he became a victim of that crisis, Gandhiji’s irrationalism in 1940s and Discovery of India is an attempt to justify, partly to justify it.

I will end Mr. Chairman however with a final tribute.

In 1947 both Gandhiji’s and Nehru’s dreams united as never before. Both wanted that communal slaughter should stop, both wanted that even if division came Muslims should live in India and Hindus and Sikhs should live in Pakistan. They both felt that their primary duty was to do their duty in India. Frankly, very few top leaders of the Congress felt that. That could be seen in the Meerut session of the ICC where Patel made his speech, Sword to be replied with Sword. When Gandhiji went on his fast on 13th of January, 1948, that was the testing hour. What he was demanding was that refugees in Delhi who had occupied Muslims houses should vacate them. Not an easy thing. They had been thrown out in Punjab, massacred there, come here, taken houses. They were to vacate them and let back Muslim owners.

Second demand, that India should pay 55 crores to Pakistan whose government was by that non-payment, bankrupt. Most unpopular demand.

I believe that Sardar Patel and Rajendra Prasad went to Gandhiji to protest against his fast. That demarcated the leadership.

Now if you read any account of that time and we were of course, I was a school boy…no, I think I was a first year student in the AMU at that time, I read the Hindustan Times. I read that on the first day of the hunger strike, stones were thrown at Gandhi and ‘Gandhi murdabad’ were slogans shouted in lanes and bye lanes of Delhi. On the 15th, Nehru addresses a crowd of 10,000 in front of the Red Fort and to my mind that is the kind of leadership that he signified, it liberates.

So whenever one disagrees with Nehru or even with Gandhiji, one has to do it with the greatest respect and ask the question, Would I have done it, Would anyone else have done it? Well, thank you very much for your patience.

(Lecture Delivered by Professor Irfan Habib at the India International Centre on November 22, 2014 as part of the 125th Birth Anniversary Celebrations of Jawaharlal Nehru organised by SAHMAT, New Delhi)

.jpg)