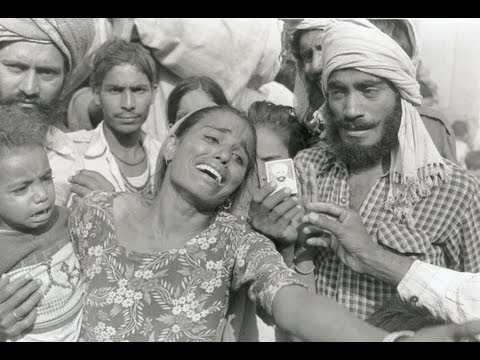

1984: Anti Sikh Riots

In the last several decades, various regions of India have suffered from outbreaks of massive mass violence. The impunity enjoyed by the perpetrators of such wide-scale organised crime has raised important questions about state accountability in the world’s largest democracy.

Major players and perpetrators of internal conflict, particularly communal conflict, anti-Dalit pogroms and violence against sections of the tribal population have all, equally speaking, enjoyed impunity. This impunity pervades different organs of the state: first, in preventing the outbreaks of such violence (the singular failure in checking mobilisation of non-state actors who espouse violence to openly arm their squads, and in arresting perpetrators of hate speech and incitement to violence are some examples); second, in registering and investigating these crimes fairly and following due process of law; third, in prosecuting the perpetrators and punishing the guilty; and fourth, in acknowledgement of the mental and physical trauma and harm in terms of measuring acknowledgement and reparation of the crimes.

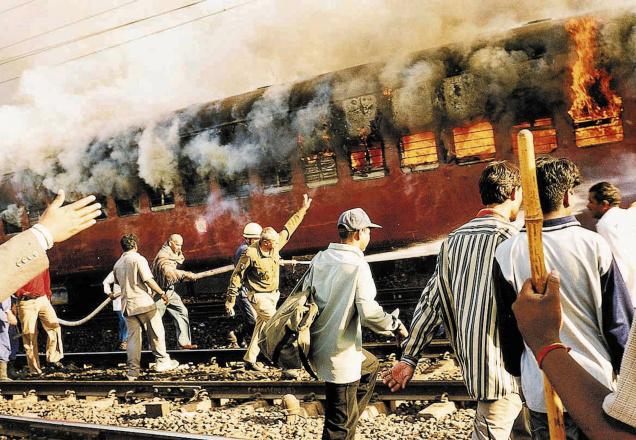

Gujarat 2002 and the uphill task that the justice struggle has taken for victims of the carnage (see CC, November 2003) is the last among a long line of sorry tales that speak of undelivered justice. The chief minister of the state, Narendra Modi, (re-elected after the pogrom, on December 15, 2002) and six cabinet ministers have been directly indicted for their involvement in mass crimes by testimonies (sometimes but not always translated into FIRs) of eyewitnesses and survivors and Crimes Against Humanity, the two-volume report of the Concerned Citizens Tribunal—Gujarat 2002. The international general secretary of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad, Dr. Praveen Togadia, has also been named. Senior members of the state police service and civil service were also directly named and indicted for overt or covert violation of the IAS/IPS service rules, Indian criminal law and the Indian Constitution. The levels of impunity related to the Gujarat carnage are staggering if we revisit those named and identified by victims as perpetrators. In all, 88 persons from the police and bureaucracy stand indicted, including then chief secretary Subha Rao, home secretary Ashok Narayan and DGP, K Chakrovarty. From the political class, 730 persons have been named and identified as perpetrators of mass crimes by this report. Many of them are members of the ruling political party and its affiliate organisations.

The justice process for victims of the post-demolition violence that rocked Bombay in 1992-93 has also similarly floundered with utter contempt being shown for issues of accountability and impunity by political actors of varying political colour and dispensation. Similarly, be it Bhiwandi-Bombay-Jalgaon in the late sixties or many other bouts of communal conflict that followed, impunity has been the norm and accountability utterly absent.

From the decade of the sixties, when the first rounds of communal violence began to erupt post-Partition and Independence, individuals and organisations identified and named by official judicial commissions of inquiry investigating the crimes have enjoyed utter impunity, be they political leaders or men in uniform. In turn, this disregard for accountability by the world’s largest democracy has resulted in the crimes themselves being regarded with greater and greater impunity by the State and by society in general. By the decade of the eighties and nineties, these crimes, shaped by this impunity, had assumed the character of full-fledged pogroms, be it Delhi 1984, Meerut-Maliana 1987 or Bhagalpur 1989. Gujarat 2002 was the full-blown version of state sponsorship and perpetration of a carnage that had clear elements of genocide.

On the periphery of these bouts of internal conflict are conflicts like Punjab, Kashmir and many states of the north-eastern region of India that have also been characterised as separatist movements. In these situations, the Indian State has often taken stringent counter-measures to quell the violence using violence. State actors have been documented as having perpetrated human rights abuses, committing excesses under the guise of restoring peace. Few, if at all, have been penalised to date.

The irony of the fact is that India, hailed for being the world’s largest democracy, has both seriously faltered on the issue of impunity for mass crimes while adopting a close door policy on human rights discourse and international scrutiny in these areas. Like the USA, the world’s most developed democracy; India refuses to ratify the need for an International Criminal Court (ICC). Though India has signed the International Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment on October 14, 1997, it has failed to ratify it.

India is, however, signatory to a number of UN declarations and instruments, including the UN Charter of 1945, the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide, the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, acceded to on July 10, 1979. Signing these treaties under international law and practice necessarily means criminalising (legislating or bringing under the purview of Indian law) the crimes enlisted under these declarations and treaties. This, too, India has not done.

Punjab

The Working Group (of the United Nations) on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances, established in 1980, reported large numbers of enforced disappearances, attributing primary responsibility to the Punjab police. The Working Group also held that officers of the Punjab police acted with virtual impunity, disobeyed judicial orders, even ignored writs of habeas corpus and intimidated family members of disappeared persons so as to make them refrain from making complaints. The Group’s 1996/97 report also mentioned the disappearance of Jaswant Singh Khalra after he filed the petition regarding illegal cremations in the High Court, alleging that many of the cremated had been arrested by the Punjab police.1

The government of India turned down an application by the Working Group to visit the country so as to discuss the matters with the competent authorities and to meet the representatives of the families of the disappeared. The representatives of the Indian government told the working group that “given the fact that the allegations of disappearances have drastically fallen in the last three years, coupled with the government of India’s commitment to investigate the old cases”, the suggestion of the Working Group regarding a visit to India is “inappropriate and unnecessary.” The government also stated that the matter of illegal cremations was now before the Supreme Court, which had instituted an inquiry by the Central Bureau of Investigation. The report concluded with the observation that under Articles 14 and 7 of the UN Declaration on the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance adopted by the General Assembly on December 18 1992, the government of India was under obligation to “prevent, terminate and punish all acts of enforced disappearance.”2

The 1997 report by the Special Rapporteur on Torture, Nigel S. Rodley, renewed his “outstanding request for an invitation to visit the country…” whose refusal was a matter of concern.3 This report focussed on widespread and systematic use of torture by the Punjab police. It said:

“By a letter of 28 April 1997, the Special Rapporteur informed the Government that he had received reports indicating that the use of torture by police in Punjab was widespread. The methods of torture reported included beatings with fists, boots, lathis (long bamboo canes), pattas (leather straps with wooden handles), leather belts with metal buckles or rifle butts; being suspended by the wrists or ankles and beaten; kachcha fansi (suspension of the whole body from the wrists, which are tied behind the back); having the hands trodden upon or hammered; application of electric shocks; burning of the skin, sometimes with a hot iron rod; removing nails with pliers; cheera (forcing the hips apart, sometimes to 180 degrees and often repeatedly, for 30 minutes or more); and the roller method (a log of wood or ghotna – a heavy pestle is rolled over the thighs or calves with one or more police officers standing upon it); and insertion of chilli peppers into the rectum.”4

In the same period, the Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions appointed by the Commission on Human Rights in August 1982, reported widespread practices of arbitrary executions carried out by the security forces. The 1997 annual report concluded that “despite the existence of legal provisions for the prosecution of human rights violators” there was de facto impunity in India. The Rapporteur also reiterated his interest in visiting the country, which he had already expressed in three earlier letters.5

The decade of political violence in Punjab has left behind a large number of victims who are still seeking justice. These people are trapped in a web of fear, rumour and myth. They need to be released from the psychology of victim-hood.

What was the government of India’s response? Mrs. Arundhati Ghose, then India’s Permanent Representative at the United Nations Office in Geneva, told the Human Rights Commission that it should adopt a cooperative rather an adversarial and “spotlighting” approach. Ms. Ghose said that instead of undertaking direct investigations, the Commission should work only in consultation with the government. She declared: India had a broad range of guarantees built within its constitutional system to safeguard human rights, and did not require foreign intervention: India’s respect for human rights was rooted in its ancient philosophy and culture and, even in the modern context, predated its accession to the United Nations. The tough stand taken by Ms. Ghose received praise in the Indian press, some of them greeting her as the “Iron Lady” for her capacity to “look the western bullies in the eye.”6

The disdain of the Indian State for public and international accountability has been, in a sense, matched by the ineffectiveness of international players despite treaties, conventions and other mechanisms enacted to hold states accountable. In the process, lives such as that of Jaswant Singh Khalra and several other human rights activists and lawyers, who have disappeared while trying to expose the truth, were also lost.

Today, the survivors and the families of the disappeared in Punjab have been, since 1997, engaged in a life-exhausting and fruitless pursuit of accountability and justice in this matter before the NHRC. The critical issue of the mass cremations of the disappeared in the Amritsar district of Punjab (2098 cremations) is pending before the NHRC for adjudication on the critical issue of what constitutes (quantity and quality) reparation. Interestingly, the discourse takes place while even due acknowledgement of the crimes is challenged.

What has so far remained a futile struggle for acknowledgement, justice and accountability has been tirelessly documented in a recent publication, Reduced to Ashes.7 It is a story that reveals the contradictions between the constitutional law, as a conceptual framework, and the rule of law as the emanation of power, a pragmatic enterprise run by the Political Establishment whose realities are as banally brutal as noble are its constitutional professions.

In the interim report of the Committee for Coordination on Disappearances in Punjab (CCDP) published in July 1999, and its summary later published by SAFHR as a paper in 2002, the author, Ram Narayan Kumar, discusses the suicidal bereavement of Ajayab Singh, a fifty-five year old sarpanch of a village in Amritsar district who took poison and died inside the Golden Temple on July 7, 1997, after writing an “epistle in black ink” to explain his reasons. His eldest son, Kulwinder Singh, a public servant associated with village administration, had disappeared after having been taken into police custody at a check-post across Amritsar’s railway station on December 20, 1991. The life-exhausting and fruitless pursuit of accountability and justice, which lasted more than five-and-a-half years, finally broke Ajayab Singh’s spirits. His thirty-five year old married son with three young children, disappeared into the jaws of the Punjab police, and Ajayab Singh could not do anything to establish that his son’s life had not been a chimera. The State’s power of denial obliterated this life retrospectively. The constitutional guarantees of human rights and the rule of law seemed to have no meaning. Ajayab Singh’s epistle in black ink said, “self-annihilation is my only way out of a life that leaves no scope for justice.” Ajayab Singh’s is not an isolated example. The CCDP’s survey of 838 incident-reports of enforced disappearances, conducted in the period of one-and-a-half years from November 1997 to May 1999 and published in their July 1999 Interim Report, shows that 222 relatives of the victims died under trauma. In 500 of 838 incidents, the surviving relatives report morbid psychological effects, including clinical insanity. It is in this situation that they have been waging an accountability and impunity struggle before the National Human Rights Commission. Significantly, in this recently published treatise that painstakingly documents the “inner landscapes” of expectations of the victim survivor families, in spite of their experiences of State atrocities, they are not riveted to notions of revenge. They only seek acknowledgement, reparation of wrong to the extent that is legally feasible and the end of impunity.

Reduced to Ashes: The Insurgency and Human Rights in Punjab is the final report of the Committee for Coordination on Disappearances in Punjab (CCDP), which focusses on human rights abuses that occurred in the period from 1984 to 1994. It is an attempt to tell the truth about political killings, enforced disappearances, torture, arbitrary arrests and prolonged unlawful detentions that became the stock-in-trade of the anti-insurgency operations in Punjab. It reveals the complex denial by the state agencies and their defenders and the institutional participation in the scheme of impunity. It does not take sides on the political guilt or innocence of the victims, eschews rhetoric and, significantly, stays clear of the quicksand of political solutions. The report, however, lays bare the parallelism of the rhetoric of rights and the reality of extreme human rights abuses that bedevils the Indian democratic paradigm.

Interestingly, the inquiry being conducted by the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) under the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court, in the disappearances and illegal cremations in Punjab, has also floundered deeply. Every attempt to bring justice to the victims, reform the institutions in order to achieve transparency, structural equality and democracy, has been frustrated by powerful persons linked with the previous administration that perpetrated the horrible abuses in the mistaken belief of defending the integrity of the state. Their demand for amnesty has found support in the highest quarters of the Indian government. On August 19, 2001, the union home minister spoke at a function organised by the Hind Samachar group of newspapers at Jalandhar, to announce that the government was “contemplating steps to provide legal protection and relief to the personnel of the security forces facing prosecution for alleged excesses during anti-insurgency operations” in Punjab, Kashmir and the north-eastern provinces of India. According to a report in The Asian Age, the union home minister indicated “some form of general amnesty” and suggested that “forces deployed to combat terrorism anywhere in the country must be given special rights and powers”.

KPS Gill, former director-general of Punjab police, welcomed the move and, according to a story in The Indian Express, repeated his charge that the cases against police officers “were based on concocted evidence by the investigating agencies acting under undue and extra-constitutional pressures”. The home minister’s announcement was hailed also by the Communist Party of India (CPI) and the Congress party, which promised to “withdraw all the cases against the innocent cops” if voted to power. The subsequent state assembly elections in Punjab returned the Congress to power, and its government in the state is led by Amrinder Singh, the scion of Patiala royalty who converted the issue of amnesty to police officials into an election pledge. It is in this context and the declared positions on impunity by both the state and the union government that the NHRC will, in the case of the illegal cremations pending before it, have to weigh the evidence of human rights crimes offered in the CCDP report. Only then will it be able to proceed in the matter of abductions leading to illegal cremations by the Punjab police in Amritsar district.

The decade of political violence in Punjab has left behind a large number of victims who are still seeking justice. These people are trapped in a web of fear, rumour and myth. They need to be released from the psychology of victim-hood. The data contained in this report shows troubling levels of impunity within the state and central administration. For example, the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), India’s premier investigative agency, failed to seriously and properly investigate the matter of illegal cremations as entrusted to it by the Supreme Court in 1995. At the conclusion of their investigation, the CBI submitted three lists of identified, partially identified and unidentified cremations conducted by the police. These lists reveal several discrepancies. The CBI failed to identify persons it could easily have identified from complaints filed by victim families, interviews with them, police records and press reports; it duplicated records and listed persons who had been cremated by their families, not by the police; and it failed to properly investigate the cremations of additional persons reported as having died in the same encounters and also the cremations of others listed under the same police reports. Thus, it did not go beyond the police records to examine the actual extent of illegal cremations in Amritsar district.

The report also shows how the police regularly and openly flouted legal procedures for arrest and search. The police failed to respond to families’ requests for information regarding the abducted persons; they extorted money from victim families and they travelled outside their jurisdiction to capture people. The volume documents the prevalence of custodial torture and traces the patterns of its use against family members, the police’s destruction, expropriation or damage of property belonging to victim families and the complicity of the judiciary in ensuring impunity for custodial torture and death.

Not surprisingly, the defenders of impunity in Punjab have been vocal against the human rights litigation that seeks accountability and restitution of hideous abuses of power. On June 8, 2001, KPS Gill published an article in The Hindustan Times titled “Man in Uniform Demands Justice”. The article argued that “those who risked their lives in the defence of the State” are being subjected to “a humiliating process of prosecution in a multiplicity of cases that were intentionally and maliciously lodged… as a strategy of vendetta by the front organisations of the defeated terrorist movement”. Gill asked: “How long will men continue to fight and to die for India if no one in the country speaks for the men in uniform? Can the power of the State survive the erosion of the confidence and authority of those who protect it?”

This rhetoric of morale and the national security is evidence of attempts to thwart the process of accountability. In his foreword to a book titled Human Rights and the Indian Armed Forces, Gill criticised the “systematic adoption of human rights litigation as a weapon against agencies of the State by criminals and by violent groups who themselves reject democracy and seek the overthrow of lawful and elected government”. According to him: “An overwhelming proportion of public interest human rights litigation is today being initiated by front organisations of criminal conglomerates and of virulent underground terrorist movements in a systematic strategy to harass and paralyse security forces and the police.”8

Kashmir

The conflict in Kashmir has left thousands dead. Human rights abuses have continued unabated. The Kashmir conflict not only continues to raise the spectre of war between India and Pakistan, but it also continues to produce serious human rights violations against Kashmiri civilians and those living in Jammu and Ladakh regions: summary executions, rape and torture. Both the Indian military and armed groups commit human rights abuses. There is a systematic pattern of human rights abuses and a regime of impunity that the Indian government has used to eliminate what it views as a security threat by any means necessary.

A humanitarian crisis of sorts exists in Kashmir. Kashmiri civil society seeking to address urgent issues and Kashmiri groups that have eschewed violence but continue to politically campaign for independence, have found an ever-narrowing space to work within. Their situation has rarely been covered by international media, and 13 million Kashmiris are isolated from the world as their society continues to be torn apart by the ravages of the conflict.9

Physicians for Human Rights, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International and other international human rights groups began reporting on human rights in Kashmir in the late eighties. A number of reports were published expressing deep concern at human rights abuses committed on all sides, particularly a systematic pattern of human rights abuses and impunity by the Indian government.

But the Indian government has banned international human rights groups like Amnesty International from visiting. Even the ICRC (International Committee of the Red Cross) was banned for a number of years and was only permitted limited access to officially listed prisons and Joint Interrogation centres to ensure the fair and humane treatment of the thousands of imprisoned Kashmiris. ICRC operations in Kashmir are severely curtailed by a very restrictive Memorandum of Understanding with the Indian government which does not permit unfettered access, unannounced visits to detention centres, or access to the “unofficial” prisons and detention centres.

Courtesy: Dar Yasin, AP

Given that international human rights groups have not been permitted to visit Kashmir, the primary responsibility of human rights documentation, research and advocacy has fallen on local Kashmiri actors. It has been a lonely and dangerous endeavour for those who have taken up this important work. For the most part, Kashmiri society was not adequately prepared to contend with the crisis of human rights issues which has dominated life in Kashmir since the early nineties. Proper human rights work has not been adequately addressed and understood by Kashmiri political groups involved in an independence struggle. At the beginning of the nineties, many Indian human rights organisations visited Kashmir and documented the human rights situation through their reports. Groups from South India, such as the Andhra Pradesh Civil Liberty Council (APCLC), also documented the human rights situation in Kashmir, but these reports were dismissed by the government of India as misleading and intended to “demoralise” the army.

Within Kashmir, the Kashmir Bar Association and the Jammu Bar Association also did some documentation but this did not meet professional standards. One organisation that documented the human rights violations in Kashmir over the past decade was the Institute of Kashmir Studies (IKS). Founded in 1992, the IKS brought out 40 publications and studies on human rights within Jammu and Kashmir. However, since many IKS office-bearers were affiliated with a right-wing political party, independent observers have questioned the reports of the IKS as it was accused of politicising human rights issues. After the detention of its chairman in November 2002 under the Public Safety Act, the president of Jamaat-e-Islami took over the responsibility of IKS. Soon after the detention of its chairman, the president of Jamaat suspended the activities of IKS. Thus, political forces interfered in the human rights work of the IKS, while the credibility of the well-researched IKS reports were impacted by perceived involvement of the very same.

Today, the Public Commission on Human Rights (PCHR), an independent organisation of the Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society (CCS), is documenting the human rights situation on a monthly basis. Besides an Informative Missive called the Kashmiri Women’s Initiative for Peace and Disarmament (KWIPD), a constituent of CCS, through its quarterly magazine “Voices Unheard”, documents and disseminates information on violations against women and children.

Thousands of people have been the victims of enforced disappearances by the government. Another CCS member, the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP), has brought together hundreds of Kashmiri families whose members have been the victims of Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances (EID) by the Indian government. The APDP is a collective campaigning organisation that seeks truth and justice on this severe human rights issue in Kashmir. Recently, in April 2003, APDP organised a world wide hunger strike coordinated in different cities across the world, pressing for an end to disappearances, prosecution of perpetrators, and appointment of a commission to probe into all enforced disappearances. Despite wide participation, this protest went unreported in the mainstream Indian media.

Many eminent human rights defenders have lost their lives while espousing the cause of human rights in Jammu and Kashmir. After the assassination of human rights activists HN Wanchoo, Dr. Ashai and Dr. Guroo, things became especially difficult for human rights defenders. Many who had joined the human rights efforts in the early nineties disassociated themselves from the campaign feeling intimidation from the Indian State and militant groups. In many ways, the local human rights movement was neutralised after the assassination of Jaleel Andrabi on March 23, 1996, with the alleged involvement of Indian counter-insurgency squads. It was at that time that Washington based Asia Watch (of Human Rights Watch), a world wide human rights organisation, described Kashmir as the most dangerous place in the world for human rights defenders.

Impunity is granted to the security forces under Section 6 of the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA) which reads as: no prosecution, suit or other legal proceedings shall be instituted except with the prior sanction of (the) centre, against any person in respect of anything done or purported to be done in exercise of the powers conferred by this Act. There are innumerable cases in which army officials have carried out liquidations and assassinations of non-combatant Kashmiris, but no action has been taken against them. This has occurred notwithstanding the Supreme Court’s directive that, while deciding the legal validity of the AFSPA, complaints against armed forces must be investigated.

Political impunity sustains itself on an institutionalised lie. When it comes to political assassinations, the perpetrators are convinced they have better served their country by torturing, killing, or making the enemy disappear, and all this convinces them that they are unaccountable and have license to do anything in the name of patriotism and the “territorial integrity of India.”

The whole system of human rights violations functions on the basis of impunity, of which legal impunity is one facet. Another facet is political impunity, which sustains itself on an institutionalised lie. When it comes to political assassinations, the perpetrators are convinced they have better served their country by torturing, killing, or making the enemy disappear, and all this convinces them that they are unaccountable and have license to do anything in the name of patriotism and the “territorial integrity of India.”

The very concept of impunity under international human rights and humanitarian law is encapsulated in the UN Principles on Protection and Promotion of Human Rights Through Action to Combat Impunity, 1997. This set of principles voices the victims’ right to the truth, to have knowledge of the atrocities, and to remember the crimes. They also enumerate in some detail the need and functioning of Public Commissions to examine such mass crimes and to protect witnesses and their testimonies. Most significantly, they articulate the right to justice for the victims. Principle 19; Safeguards Against the Use of Reconciliation or Forgiveness to Further Impunity, states that “There can be no just and lasting reconciliation without an effective response to the need for justice; an important element in reconciliation is forgiveness, a private act which implies that the victim knows the perpetrator of the violations and that the latter has been able to show repentance.” Principle 20; Duties of States with Regard to the Administration of Justice, succinctly sums up the concept of Impunity under International Human Rights and Humanitarian Law. “Impunity is a failure of States to meet their obligations to investigate violations, take appropriate measures in respect of the perpetrators, particularly in the area of justice, to ensure that they are prosecuted, tried and duly punished, to provide the victims with effective remedies and reparation for the injuries suffered, and to take steps to prevent any recurrence of such violations. ”

Tragically, the Indian State has near-institutionalised impunity when it comes to the committal of mass crimes.

Note: The struggle for justice for victims of the Gujarat 2002 carnage and the attendant impunity was widely covered by us in last month’s cover—Godhra Re-visited and The Long Road to Justice. Hence this month’s cover concentrates more on the two other regions that were subject matter of the conference.

(This report captures most of the issues raised at a recent conference held at the Harvard School of Public Health on Human Rights and Impunity – Towards Accountability in India. It relies heavily on the background papers presented by three regional activists – Ram Narayan Kumar on Punjab, Pervez Imroz on Kashmir and Teesta Setalvad on Gujarat. Justice JS Verma, former chairperson of the NHRC was the keynote speaker at this conference jointly sponsored by the Harvard School of Public Health (FXB Centre for Health and Human Rights), Harvard Committee on Human Rights, Harvard Law School, MIT Programme on Human Rights and Justice. The conference was organised after initiatives taken by Indian professionals living in Boston and Cambridge).

Footnotes

1 E/CN. 4/1996/38, Commission on Human Rights, Fifty-second session, Report of the Working Group on Enforced on Involuntary Disappearances, paras 236-240; E/CN. 4/1997/34, para 181—from Background Materials by Ram Narayan Kumar for the Conference

2 Ibid, paras. 31, 184, 249, 251

3 /CN. 4/1998/38, 24 December 1997, Observations

4 E/CN. 4/1998/38, 24 December 1997

5 E/CN. 4/1997/60, December 24 1966, Report by the Special Rapporteur, Bacre Waly Ndiaye, Para. 96; 228

6 www.webpage.com/hindu/960831/22/2520a.html – ; CCPR/C/76/Add.6 17 June 1996, para 4-14, 18-19, 50

7 Reduced to Ashes: The Insurgency and Human Rights in Punjab published by SAFHR in 2003

8 Air Commodore Ran Vir Kumar & Group Captain B. P. Sharma, Human Rights and the Indian Armed Forces: A Source Book, Sterling Publishers, New Delhi, 1998, pp. xiv – xv

9 Background Materials authored by Pervez Imroz, Srinagar for the conference

.png)