A subtle, steady and perceptible erosion has, and is, taking place at all levels and within all constitutional institutions, including the judiciary

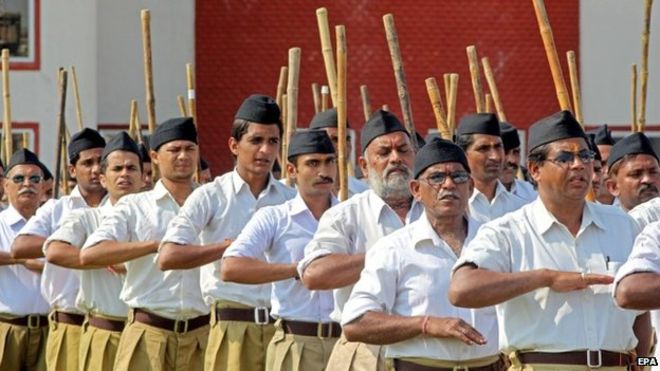

The Constitution is under attack not externally, but from within. The Indian State is under the administration of those who have no regard for the values enshrined in the Constitution. Every institution under the Constitution is being subverted and maligned. The executive today is a saffronised executive with no respect for the secular ideals found in the Constitution. The Prime Minister and his ministerial colleagues, who have taken oath to protect the Constitution have no compunction in periodically reaffirming their allegiance to the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) with an oath which says: “I must solemnly take this oath, that I become a member of the RSS in order to achieve all–round greatness of Bharatvarsha by fostering the growth of my sacred Hindu religion, Hindu society and Hindu culture”… This is the prayer that every member, pracharak of the Sangh utters with reverence:

“Affectionate Motherland,

I eternally bow to you,

O Land of Hindus,

You have reared me in comfort..,

O God Almighty,

We the integral part of

Hindu Rashtra,

Salute you in reverence,

For your cause have we girded up our

loins,

Give us your blessing

For its accomplishments.”

The domination of the RSS over the Indian executive is complete, with all the important portfolios retained by them, and small crumbs of no significance distributed amongst the BJP’s allies whose sole, albeit unholy, objective is to simply hang on to power. Constitutionally, the President is the executive head. However, with the appointment of APJ Abdul Kalam they have succeeded in installing a very pliable President who has neither political acumen nor constitutional knowledge.

The next is the assault on Parliament. With a Shiv Sena man as Speaker in the Lok Sabha and a sangh parivar man as vice-president chairing the Rajya Sabha, the takeover is almost complete. Thus, the two wings of the government — the executive and the legislature — are under the leadership of those who have no faith in the Constitution.

What about the judiciary? It is difficult to imagine that the government is not doing anything to saffronise the judiciary. When attempts at saffronisation of the bureaucracy have been so blatant, attempts to infiltrate the judiciary with men and women who are ideologically opposed to the Indian Constitution will not lag far behind.

At the lower level, the judiciary is dependent on the government whichever be the party in power. At the higher level, ie, at the level of the High Court and Supreme Court judges there is greater independence. But there is no transparency in the selection of judges. In any event, unfortunately, a commitment to Constitutional values neither is nor has governed the criteria for selection of judges. As Justice VR Krishna Iyer says: “The social justice perspective, a people–oriented credential, secular socialist essentials are frequently alien to the selection process of the brothers on the bench.”

For all we know, some of the the appointments to the bench could be primary members of the RSS who were appointed as judges later on. It is no wonder then that a former chief justice of a state high court has now become governor in a BJP–ruled state, the only apparent reason for his appointment being his close association with the VHP. This is in line with the perceptible policy of the government to appoint RSS pracharaks as governors in the states, yet another institution under the Constitution that is being manipulated and eroded.

When the Babri Masjid was about to be demolished, the only persons who could have stopped the demolition were the then Prime Minister Narsimha Rao and Justice Venkatachaliah, the judge who headed the Supreme Court bench before whom the matter was pending. Rao connived in the crime. Justice Venkatachaliah was naïve enough to accept an undertaking from Kalyan Singh, then chief minister of UP, which he never intended to keep.

After the masjid was demolished in full public view, resulting in the death of thousands of innocent people and large scale destruction of property in the riots that followed all over the country, there was hardly any feeling of righteous indignation on the benches of the Supreme Court. A routine contempt of court notice was issued against Kalyan Singh. In response, Kalyan Singh paraded the corridors of the Supreme Court and his token punishment lasted only until the court rose for the day.

In sharp contrast, the innocuous tone and tenor of an affidavit filed by Arunadhati Roy was sufficient to invoke a severe punishment from the Supreme Court. Later on, another judge, Justice JS Verma of the Supreme Court, in what is now known as the Ayodhya verdict, observed that the demolition of the Babri Masjid was the act of certain mischievous “miscreants who cannot be identified” when the whole world knew who were the perpetrators of this crime.

It is a sad reflection on the Indian judiciary that when on occasions it has been called upon to deal with ‘secularism’ as enshrined in our Constitution, it has dithered, it has displayed unbecoming traits leaning in favour of the majority as against the minority community.

Soon after the demolition of the Babri Masjid, someone installed a ramshackle Ram Mandir on the site of the demolished mosque and sought protection for the same from the court. It was patently an illegal structure put up by “miscreants” who were plainly trespassers in law. Yet, Justice Tilhari, who in his wisdom found that Lord Rama has a place in the Indian Constitution, gave protection to the structure and allowed worship and darshan for the Hindus (Vishwa Hindu Adhivakta Sangh vs. Union of India — Judgement delivered on 1-1-1993).

A special leave petition filed against this judgement was summarily dismissed by the Supreme Court. The government enacted an ordinance on January 7, 1993, the sole object of which was to permanently establish and legitmise the make shift Ram Mandir. When this ordinance (which later became an Act) was challenged in the Supreme Court, the majority judges (Judgement of Verma J.) upheld this very provision in the law (Section 7), which sought to maintain the status quo as on January 7, 1993, on the specious plea that in the demolition of the Babri Masjid, it was the Hindus who suffered their rights of worship which they were exercising from December, 1949 until December 6, 1992.

Further, Justice Verma observed that the “freeze enacted in Section 7(2) only enabled them to exercise “a lesser right of worship for the Hindu devotees” and as such the law “appears to be reasonable and just.” The learned judges conveniently forgot that in December 1949, the idols were forcibly installed within the premises of the Babri Masjid, after which action, they were sustained there through several interim orders. The minority judges on that bench of the Supreme Court rightly observed, “that the Act is skewed to favour one religion against another” (Bharucha J.).

Thus the issue of Ramjanma-bhoomi was kept alive by an order of the Supreme Court! It is the judiciary that kept this issue alive since 1949, by passing a series of orders which only favoured the Hindu community over the other. This trend set by the judiciary was to be exploited later by the communal elements in political parties, and to be hijacked and monopolised as their exclusive agenda by the sangh parivar, since about 1980.

It is a sad reflection on the Indian judiciary that when on occasions it has been called upon to deal with “secularism” as enshrined in our Constitution, it has dithered, it has displayed unbecoming traits leaning in favour of the majority as against minority community, reminding us unwittingly of what Justice Oliver Wendell Homes once said: behind every judgement lies an “inarticulate major premise.” However, their subjective conscience should not have allowed them to commit a breach of their own oath on the Constitution.

The only exception was the judgement in the case of SR Bommai (1994) wherein it has been said: “Article 25 inhibits the government to patronise a particular religion as State religion overtly or covertly. A political party is therefore positively enjoined to maintain neutrality in religious beliefs and prohibit practices derogatory to the Constitution and the laws… A political party that seeks to secure power through a religious policy or caste orientation policy, disintegrates the people on grounds of religion and caste” …

In this case the court took into account the manifesto of the BJP which stated that the “BJP firmly believes that construction of Sri Ram Mandir at Janmasthan is a symbol of the vindication of our cultural heritage and national self respect… And (that) party is committed to build Sri Ram Mandir at Janmasthan by relocating superimposed Babri structure …”.

The court also took into account that the leaders of the BJP had consistently made speeches to the same effect and that some of the chief ministers and ministers belonged to RSS and that the ministers had exhorted people to participate in the kar seva that led to the demolition. The court observed that all these materials were sufficient to hold that the state governments (which were dismissed following the demolition of the Babri Masjid) were not run in accordance with the provisions of the Constitution.

Yet this judgement was not even referred to by the Supreme Court when the election of the Shiv Sena leader Manohar Joshi (former chief minister of Maharashtra, and the present Speaker of the Lok Sabha) was upheld. In an election rally Joshi had sought votes stating that the first Hindu state will be established in Maharashtra with the Sena–BJP victory. The latter judgement gives the distinct impression that canvassing on the basis of Hindutva was permissible since “Hindutva is only a way of life.” What about Christianity? Is it not a way of life? Is Islam not a way of life? Thus, Hindutva got judicial reprieve and thereby the government at the Centre and in Gujarat today gets legitimacy.

In the 1992–93 riots in Bombay, none could doubt that the worst culprit was Bal Thackeray who had repeatedly incited the mobs through his mouthpiece, Saamna. Since the the Congress government was not taking any action against the Sena leader, two concerned citizens moved the Bombay High Court with all the newspaper articles and adequate documentation seeking direction to sanction prosecution of Thackeray. The two judges who heard the petition simply turned down the plea on the basis that past wounds and atrocities should be swallowed and forgotten because of apparent peace in the city. Worse still, the division bench of the Bombay High Court held that the provocative exhortations by Thackeray to his cadres on January 9, 1993 were not against all Muslims “but only against anti-national Muslims.”

What is even more regrettable is that the SLP filed against the judgement in the Supreme Court was summarily rejected, giving sanction to, ‘kill, loot and forget!’ Much later, when Bal Thackeray was arrested, a lower Court in Mumbai released him on a technicality and the Bombay High Court has had no time in the last three years to hear a review petition against the said order.

While the bomb blasts cases have been going on, almost on a day–to–day basis for the past several years, the judiciary has simply been postponing the case against those accused for the Babri Masjid demolition (which include LK Advani & Co.) for the last nine years!

On December 12, 1992, Narasimha Rao, by a notification, banned the RSS, the VHP and the Bajrang Dal under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967. This ban had to be confirmed by a judicial tribunal under the Act. Justice PK Bahri, a retired judge of the Delhi High Court who sat on the tribunal confirmed the ban on the VHP but quashed the ban against the RSS and the Bajrang Dal. He however spoke of “the laudable objects pursued by VHP.” So the Ram Janmabhoomi movement became a laudable act by virtue of a judicial pronouncement.

The issue of Ramjanma–bhoomi was kept alive by an order of the Supreme Court! It is the judiciary that kept this issue alive since 1949, by passing a series of orders which only favoured the Hindu community over the other.

What the judge said about the RSS discloses his “major inarticulate premise.” According to him: “The word “Hindu” has been firmly imprinted in our national mind, was radiantly reflected in our freedom struggle against the British as well. The fight was essentially for certain ideals associated with the word Hindu, and not for mere political independence or economic rights.” No wonder then that he came to the conclusion that the accusation that the RSS is opposed to Muslims is wrong. The question is, how did the then Prime Minister select such a person to head a judicial tribunal?

When Graham Staines and his two innocent children were so tragically burnt to death on the night of January 22/23, 1999 by Dara Singh in association with members of the Bajrang Dal, the government promptly appointed Justice Wadhwa, a sitting judge of the Supreme Court to hold an inquiry, inter alia on “the role, if any, played by any…organization…or individual in connection with” the killings. Within days, before the commission could begin it’s work, LK Advani, as Union home minister had granted a character certificate to both the VHP and the BD, on the floor of the Lok Sabha. He said that he knew these organisations well and they were incapable of criminal acts. What happened thereafter is well known.

Despite the investigations and depositions of police officers and counsel before the commission that revealed the clear links between Dara Singh and the sangh parivar outfits, the learned judge was in a great hurry, despite the submissions made by the commission’s advocate, Gopala Subramaniam to nullify the link. Justice Wadhwa categorically held that Dara Singh alone was responsible and that no “authority or organisation was behind the gruesome killings.” Thus Advani stands vindicated.

Fortunately for India and the founding principles of the Indian State under the Indian Constitution, the judiciary has not been entirely influenced, ideologically. It remains, with all these major deviations, the most secular institution under the Constitution, as compared to the other two. It is still the judiciary and the judiciary alone can resuscitate constitutional values to their original intent. However, we need to be warned of the subtle, steady and perceptible erosion that has been, and is, taking place at all levels and within all constitutional and democratic institutions, including the judiciary. One of the main causes for anxiety is the lack of transparency in the matter of selection and appointment of judges. Coupled with this is the lure that is offered to judges who are about to retire-with commissions and tribunals all legislatively sanctified as reserved for retired judges as also seats in the Rajya Sabha.

Added to this list is now the governor’s post. Even when there are no constitutional or statutory commissions to head that retired judges can be appointed to, the Government can always, by its executive orders create one like the recent Constitutional Review Commission — the sole purpose of which was to make use of retired judges to create doubts about the Constitution, in the minds of the people.

Archived from Communalism Combat, September 2002, Anniversary Issue (9th), Year 9 No. 80, Your lordships, beware!