Like the average Hindu, the average Hindu policemen also believes that Muslims, generally, are cruel and violent by nature

It is not very difficult to identify reasons behind the discriminatory beha-vior of the police. The conduct of an average policemen is guided by those predetermined beliefs and misconceptions which influence the mind of an average Hindu. Like the average Hindu, the average Hindu policemen also believes that Muslims, generally, are cruel and violent by nature.

In the course of my study, I spoke to a large number of policemen working with different ranks. I was amazed to find that most of them seriously believed that apart from being cruel and violent, Muslims were untrustworthy, anti-national and easily influenced by a fanatical leadership and could indulge in rioting at the slightest provocation. Generally the policemen were in agreement that Muslims initiated riots. When I confronted many of them with the question as to why Muslims should start a riot as they suffered more, they replied with arguments that an average Hindu would use.

It is but natural that after being convinced of the mischievous role of the Muslims in riots most policemen do not have any doubts regarding the ways and means to check them. They sincerely believe that there is only one way to control a riot and that is to crush the mischief-mongering Muslims. Whenever an instruction is received from the state government or senior police officials to deal with the rioters firmly and ruthlessly, these instructions are interpreted in a prejudiced and biased way. Firmness and ruthlessness towards rioters is interpreted as firmness and ruthlessness towards Muslims. The various forms of firmness have distinct meanings: arrest means arrest of Muslims; search means searches of Muslim houses; and police firing means firing on Muslims.

Even in those riots where Muslims suffered from the very inception of rioting or where the killings of Muslims was totally one-sided, the policemen gave a very interesting picture of their way of thinking. It is not only during riots that they would believe that the riot was caused by the mischief of Muslims. While talking to some of the policemen posted in Bhagalpur (1989) and Bombay (1992-93), I was amazed to find that the perception of Muslims being violent and cruel was so deeply in-built in their psyche that even after admitting the disproportionate destruction of Muslim life and property, they had many “reasons” to deny the suggestion that “naturally non-violent and pious Hindus” were in any way responsible for the damage to the Muslims.

It is a common sight in the towns of northern India that the reinforcements sent from outside during communal tensions, make their lodging arrangements in temples, dharmshalas and parks in Hindu localities or the space available in Hindu homes and shops

It is this psychology of the policemen which guides their reactions during communal strife. While combating riots, they start searching for friends among Hindus and foes among Muslims. It is a common sight in the towns of northern India that the reinforcements sent from outside during communal tensions, make their lodging arrangements in temples, dharmshalas and parks in Hindu localities or the space available in Hindu homes and shops. When the shops are closed during curfew, food, tea and snacks are supplied to them by Hindu homes. Members of the majority community, who in normal times may keep a distance from the police just like the members of the minority communities, suddenly see policemen as friends during communal tensions.

It is their natural expectation of a ‘friendly’ police that it will not use force against them. Whenever, the police uses force against Hindus, their reaction is that of an amazed and cheated group. The FIR lodged by Sri Ajit Dutta, D.I.G. during the riots of Bhagalpur (1989), very candidly underlines this mentality. It’s perusal reveals the interesting incidents of a law-breaking mob of Hindus, congregating on the road during curfew hours, expressing its dismay and anger when Mr. Dutta threatened them with police firing.

I am reminded of a similar personal experience at Allahabad (1980) when in Gadiwan Tola, I warned a Hindu mob bent upon rioting, that we would open fire if they did not disperse. I found that the crowd did not take it seriously at first and thought it was a joke. Subsequently, when they heard me ordering the head constable to open fire from his carbine, there was a clear look of disbelief and surprise in their eyes.

How far this deeply entrenched perception of Muslims being solely responsible for the riots and strict behavior towards them being the only way to quell a riot, affects the reactions of a policeman, may be illustrated with the example of Hashimpura where the savagery and horrifying non-professionalism of the police behavior is a matter of national shame.

The riots in Meerut (1987) were unprecedented in the toll of human life and for the long period of continued and unabated violence. The magnitude of the riot which started on May 17, 1987 can be gauged from the fact that to deal with it, the services of about 50 gazzetted police officers and magistrates, along with more than 70 companies of P.A.C., para-military forces and army were pressed in. The policemen deployed here harboured all the above mentioned beliefs and prejudices. When their tremendous round-the-clock vigil could not control the violence, some of them resorted to an act which could have not been imagined.

Being fully convinced that riots in a civilised society could be ended only by teaching the Muslims a lesson, one section of the P.A.C. picked up more than two dozen Muslims from a locality known as Hashimpura on the 22nd of May, where house-to-house searches were going on and killed them at two places in Ghaziabad, after transporting them there in one of their trucks.

I was Superintendent Police, Ghaziabad, at that time. After receiving the information, I got two cases registered against the P.A.C. The cases were handed over to the Uttar Pradesh C.I.D. After eight years of investigations, a charge sheet has been filed against the erring personnel of the P.A.C., only recently (1995).

Why should the P.A.C. commit such a detestable act? I had the opportunity to talk to a large number of policemen deployed in Meerut in this period during my tenure as S.P., Ghaziabad (1985-88) as also during the course of the present study. I wanted to understand the motivating factors behind such a heinous offence. The analysis of the psychology of these men will help us appreciate the relationship between the police and members of the minority communities.

Firmness and ruthlessness towards rioters is interpreted as firmness and ruthlessness towards Muslims: arrest means arrest of Muslims; search means searches of Muslim houses; and police firing means firing on Muslims.

Most of the policemen posted in Meerut in 1989 thought that the riots were the result of Muslim mischief. They were also of the opinion that Meerut had become a mini-Pakistan because of the stubbornness of the Muslims and that it was necessary to teach them a lesson in order to establish permanent peace in Meerut. They were badly affected by rumours which suggested that Hindus in Meerut were totally vulnerable to Muslim attacks. Their belief that Muslims of Meerut deserve a suitable lesson resulted in Hashimpura.

Instances like Hashimpura worsen the inimical relationship between Muslims and the police. This relationship is clearly visible during communal tension. We find that many riots start with a Muslim attack on the police. Quite often the presence of the police in a surcharged atmosphere fills Muslims with anger. Reacting to the demolition of the Babri mosque in Ayodhya, angry mobs of Muslims in other cities, venting their feelings of resentment on the street initially chose the police as their targets rather than ordinary Hindus.

There are many examples of communal rioting in which the trouble started as a clash between the police and the Muslims and then turned into a Hindu-Muslim conflict. The Idgah incident of Moradabad (1980) is an important example of this trend.

The most interesting example of the hostile relationship between Muslims and the police can be found in the behavior of a police party entering a Muslim locality during communal tension. The briefing, preparation and weaponry of this party intending to enter a Muslim locality for arrests, or searches, or even normal patrolling is as if it is going to enter enemy territory. I have seen many such groups and always found them full of apprehension and fear.

Their behavior is not without reason. Alertness on their part is necessary as they may be attacked at any time. Who is responsible for these feelings of distrust and enmity? Perhaps the seeds are to be found in the terms ‘we’ and ‘they’ used by police officials for Hindus and Muslims during their conferences, organised to devise ways and means to deal with a communal situation.

Reporting of facts, investigation into and prosecution of participants in communal riots is another area where we find a clear communal bias in police behavior. The reporting of facts is done at various levels. Intelligence reports being prepared at the level of police stations and intelligence units to be sent to government and senior police formations are normally affected by this bias.

For example, I have found one interesting thing in the lists of communal agitators being maintained at various police levels in Uttar Pradesh. For most of the officials responsible for maintaining such lists, a communal agitator means a Muslim communal agitator. Even during those days when Hindu communal forces were active in the movement of Ram Janambhoomi movement, it was very difficult to find names of Hindu inciters in the list.

What damage this bias can inflict on police professionalism can be understood from the incident of the destruction of the Babri Mosque. It is evident from the charge-sheet filed by the C.B.I. that the demolition of the mosque was the result of a well-planned conspiracy. None of the intelligence agencies could report this fact before the 6th of December, 1992.

A very heinous examples of this bias in reporting facts is available at Bhagalpur (1989). One hundred and sixteen Muslims were killed in village Logain on the 27th of October 1989. This brutal massacre was enacted by the Hindus of Logain and the neighbouring villages. Logain village is 26 kilometres from the district headquarters of Bhagalpur, with the police station only 4 kms away at Jagdisgpur. The Muslims killed were buried in the fields and cauliflower was grown over their dead bodies.

Out of the 181 Muslim inhabitants of the village, 65 survivors and their attackers went to many places, including Bhagalpur town, and reported this ghastly incident. Details were published in local and national newspapers. Inspite of this, the district and police administration of Bhagalpur kept denying any such happening till the 8th of December 1989, when a police party led by Sri Ajit Dutta, D.I.G. ,dug some of the dead bodies out of the fields.

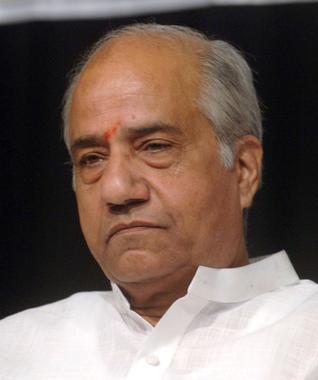

Vibhuti N. Rai

(Excerpted from the writer’s recently published book, ‘Combating Communal Conflicts —Perception of Police Neutrality During Hindu-Muslim Riots in India’)

Archived from Communalism Combat, March 1998, Year 5 No. 41, Cover Story,

.gif)