Courtesy: Getty Images

"If observance of Truth was a bed of roses, if Truth cost one nothing and was all happiness and ease, there would be no beauty about it."

– Mahatma Gandhi, Harijan, September 26, 1936.

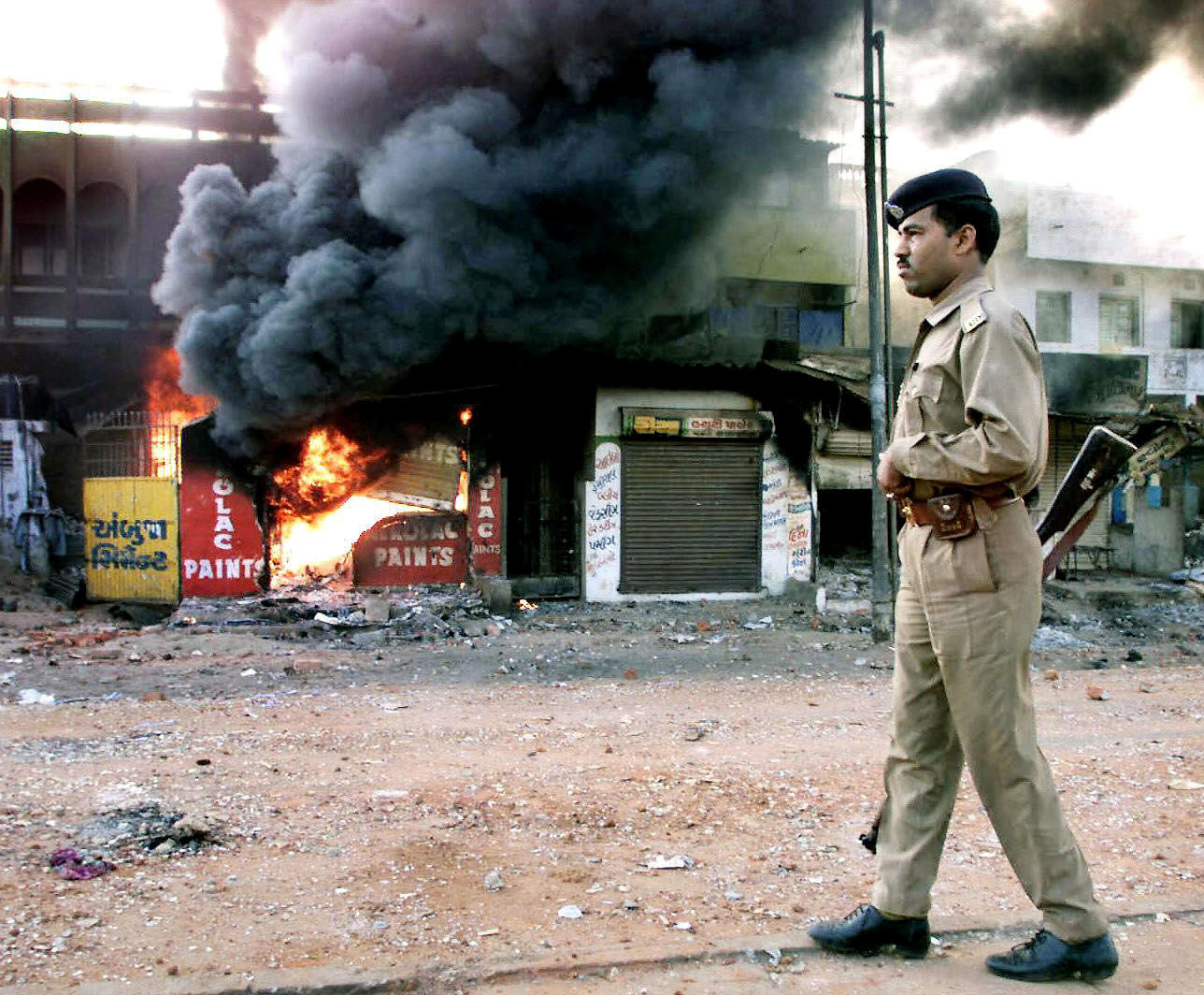

In the weeks following the Godhra arson it became increasingly evident that the Gujarat genocide had been crafted in minute detail, meticulous orchestration and planning that resulted in the widespread bestiality witnessed during the carnage. Militias numbering several thousand persons, trained to disseminate rumour, barter on hate and fuel frenzy, erupted into countless streets across the state. Their venom spread through major cities like Ahmedabad, Vadodara and Bhavnagar, and swept through several districts, Kheda, Panchmahal, Dahod, Mehsana, Anand and elsewhere in Gujarat.

Newspaper reports as well as Communalism Combat’s special issue, "Genocide – Gujarat 2002" (March-April 2002), traced numerous efforts by individuals in the highest echelons of the state government and bureaucracy to prevent the functioning of the law and order machinery and administration. Officers who did their jobs sincerely were punished. Those who danced to the tunes of Narendra Modi’s Machiavellian flute all flourished.

Amidst this bloody landscape, a silent operation was afoot, conducted by some of the finest in the police force. The Nanavati-Shah Commission opened a window of opportunity for the honest officer to play his card. From mid-2002 onwards a handful of police officers have placed a wealth of scandalous material before the commission to document, in detail, the execution of the gory genocide.

On July 6, 2002, the then additional director general of police (ADGP)-intelligence, RB Sreekumar filed his first affidavit before the commission. The affidavit was deemed a privileged document until the commission released it two years later. (After the BJP and its allies were ousted from power at the Centre, the Modi government in Gujarat moved stealthily to expand the enquiry commission’s terms of reference to include investigation into the role of the chief minister and senior officers in the post-Godhra violence. The obvious intention was to pre-empt the newly formed UPA government at the Centre from appointing another commission of enquiry covering all aspects of the genocide.)

Thereafter, RB Sreekumar filed three more affidavits before the Nanavati-Shah Commission, on October 6, 2004, on April 9, 2005 and on October 27, 2005. His submissions before the commission reveal a startling pattern of state complicity and duplicity in the events related to the Gujarat genocide of 2002 and the government’s continuing efforts to subvert the process of law and justice. But his insistence on the truth in the face of such persistent and powerful adversity proved costly. In early 2005, barely a few months after he had filed his second affidavit before the commission in October 2004, Sreekumar was superseded for promotion to the post of director general of police (DGP), a post he richly deserved.

In his third affidavit dated April 9, 2005 filed before the commission, Sreekumar narrates the state government’s efforts to browbeat him into obscuring the truth. A tape recording and transcripts of a conversation that took place between Sreekumar and the undersecretary of the home department, Dinesh Kapadia, on August 21, 2004, form an annexure to this affidavit. With Sreekumar’s deposition before the commission due on August 31, 2004, Kapadia tried to persuade Sreekumar to depose in favour of the state government. Three days later, on August 24, 2004, GC Murmu, secretary (law & order), home department, and Arvind Pandya, government pleader before the Nanavati-Shah Commission, did their best to further browbeat Sreekumar regarding his deposition. This conversation was also taped and the tape recording and transcripts were submitted to the commission. These are crucial documents that record the pressure being exerted on Sreekumar by Murmu and other officials, including a lawyer appearing for the state government, to conceal the truth from the Nanavati-Shah Commission.

These were not the only attempts made to restrain an honest police officer. To his third affidavit, Sreekumar also annexes a copy of a personal register maintained by him between April 16 and September 19, 2002. Cross-signed by OP Mathur, the then inspector general of police (IGP) (administration & security), the 207-page register contains a telling narrative of repeated efforts by the chief minister and top bureaucrats to coerce an upright officer who was proving to be a serious thorn in the flesh for the state government.

On April 19, 2005, Sreekumar also moved the Central Administrative Tribunal (CAT) challenging his supersession for the post of DGP. In September 2005 (after he had filed three affidavits exposing the state’s complicity in the post-Godhra violence) the Gujarat government ordered a departmental enquiry against Sreekumar on the basis of a charge sheet issued by the state, which, in effect, questions the facts he has placed before the Nanavati-Shah Commission. After several hurdles the CAT finally delivered an order in Sreekumar’s favour on the day he retired from service i.e. February 28, 2007. The order is yet to be implemented. The state government has challenged the CAT order through an appeal filed in the Gujarat High Court. Sreekumar’s challenge to the charge sheet is a matter still pending before the tribunal.

Quoting statistics of heavy casualties among Muslims due to police firing, Sreekumar appealed to Modi to see reason and to acknowledge that it was Hindus who were on the offensive. The chief minister instructed him not to concentrate on the sangh parivar since they were not doing anything illegal

Analysis of the register

It is the duty of a competent officer in the intelligence department to collect data from various sources of which he then maintains a record. Sreekumar was issued what he interpreted as unconstitutional directives from the top man in the state. He not only resisted these verbal orders, which he clearly saw as illegal, he did more. He maintained a record of these orders for the future. Not directed by his superiors, this personal register is a contemporaneous document maintained by an officer who grasped the wider motives at work and decided to provide a detailed record of those moments.

Sreekumar’s register consisted of three columns. The first recorded the date and the time when each instruction was given, the second recorded the nature and source of the instructions that were issued and the third recorded the nature of action taken. The contents of this register provide invaluable information about the workings of the Modi regime.

Sreekumar makes his first entry on April 16, 2002. He notes that the chief minister, Narendra Modi called a meeting attended by his principal secretary, PK Mishra, the then DGP, K. Chakravarti, and Sreekumar himself. Modi claimed that some Congress leaders were responsible for the continuing communal incidents in Ahmedabad. As head of the State Intelligence Bureau (SIB), Sreekumar said that he did not have any information to this effect. Nevertheless, Modi asked him to immediately start tapping state Congress president, Shankarsinh Waghela’s telephone lines. The chief minister’s principal secretary also tried to persuade Sreekumar in this regard. Sreekumar replied that it was neither legal nor ethical to do this since they had received no information about Waghela’s involvement in any crime. A terse comment contained in the third column of Sreekumar’s register states: "The chief minister’s instruction, being illegal and immoral, not complied with."

At two separate meetings held on April 22, 2002 some officers, including Sreekumar and a few others, brought up the question of the Muslim community’s severe disenchantment with the police for its failure to register FIRs and conduct proper investigations into incidents of communal violence. At the first meeting, which was convened by the chief secretary, G. Subbarao, and where Ashok Narayan, additional chief secretary (home), and the Ahmedabad municipal commissioner were also present, Sreekumar brought up the issue of the Muslim community’s lack of faith in the state administration vis-à-vis arrests of perpetrators and recommended that action be taken. The chief secretary said such action (against Hindu perpetrators) was not immediately possible as it went against government policy. At the second meeting too, the chief secretary evaded the issue of arrests. Sreekumar’s register reads: "This response of the chief secretary was reflective of government policy of evading, delaying or soft-pedalling the issue of arrests of accused persons belonging to Hindu organisations."

On April 30, 2002, ADGP RB Sreekumar received another illegal instruction from the chief minister routed via DGP K. Chakravarti. The DGP informed Sreekumar that the chief minister had instructed him to book Congress leaders for their alleged involvement in instigating Muslims to boycott and obstruct the ongoing Class XII examinations and that he (the DGP) had told the chief minister that action could only be taken on the basis of specific complaints. The next day, on May 1, the DGP told Sreekumar that the chief secretary was being persuaded to create a policy that would allow the ‘elimination’ of ‘Muslim extremists’ disturbing communal peace in Ahmedabad. Sreekumar records his reply that this would be cold-blooded and premeditated murder with which the DGP concurred. The emergent picture exposes Modi’s plans to script yet another saga of unlawful state driven violence and the chief secretary and additional chief secretary’s willingness to go along with this. The DGP emerges as a man caught in the throes of a battle with his conscience, prompted by a little help from RB Sreekumar.

On May 2, 2002, former DGP, Punjab, KPS Gill took charge as special security adviser to Narendra Modi. Two days later i.e. on May 4, he called a meeting of senior officers for an informal briefing. DGP K. Chakravarti, the commissioner of police (CP), Ahmedabad city, PC Pande, the ADGP (law & order), Maniram, the joint commissioner of police (JCP), Ahmedabad, MK Tandon, the deputy inspector general of police (DIGP)-CRPF, Sharma, and ADGP Sreekumar were all present.

While PC Pande, the then CP, Ahmedabad (and currently DGP, Gujarat), tried to paint a positive picture about the situation, ADGP Maniram provided his frank assessment that the police force in Gujarat, and particularly in Ahmedabad city, was extremely demoralised and the situation demanded that there should be a change of (police) leadership at every level, from the CP, Ahmedabad, downward. Maniram also stated that police officers had become subservient to political leaders and in matters of law and order, crime, investigation, etc, they carried out the instructions of political masters because these individuals, local BJP legislators or sangh parivar leaders, had a lot of clout. Political leaders arranged police postings and ensured continuance in choice executive posts. Maniram pleaded for the restoration of sanity and professionalism in the police force.

Sreekumar endorsed Maniram’s assessment and informed Gill that for the past five or six years the BJP government had been pursuing a policy of (1) saffronisation/communalisation, (2) de-professionalisation and (3) subversion of the system. He explained the subtle methodology adopted by the BJP government to persuade, cajole and even intimidate police personnel at the ground level. Sreekumar gave Gill a copy of his report on the prevailing situation in Ahmedabad. He also told Gill of the Muslims’ loss of faith in the criminal justice system and suggested remedial measures. Gill, however, did not respond to these suggestions. In his register Sreekumar notes: "It is felt that Shri Gill has come with a brief from Shri LK Advani, union home minister. So he will carry out the agenda of Shri Narendra Modi, the chief minister."

On the afternoon of May 7, 2002, the chief minister, Narendra Modi summoned Sreekumar for a meeting where he asked the ADGP for his assessment of the continuing violence in Ahmedabad. Sreekumar promptly referred to his note on the prevailing communal situation whereupon Modi said that he had read the note but believed Sreekumar had drawn the wrong conclusions. The chief minister argued that the violence in Gujarat did not necessitate such elaborate analysis – it was a natural uncontrollable reaction to the incident in Godhra. He then asked Sreekumar to concentrate on Muslim militants. Sreekumar pointed out that it was not Muslims who were on the offensive. Moreover, he urged the chief minister to reach out and build confidence within the minority community. Modi was visibly annoyed at Sreekumar’s suggestions.

Quoting statistics of heavy casualties among Muslims due to police firing, Sreekumar appealed to Modi to see reason and to acknowledge that it was Hindus who were on the offensive. The chief minister instructed him not to concentrate on the sangh parivar since they were not doing anything illegal. Sreekumar replied that it was his duty to report accurately on every situation and "provide actionable, preventive, real time intelligence having a bearing on the order, unity and integrity of India".

The very next day, on May 8, 2002, the DGP informed Sreekumar that at a meeting with Gill the latter had told the DGP that (1) The police should not try to reform politicians (which meant that the BJP and the sangh parivar could continue to suppress, terrorise and attack Muslims even as the police took no action) (2) There was no need to take action against the vernacular press (who were publishing communally incendiary writing that fanned violence against the minorities) (3) The police should begin to play an active role in getting rid of the inmates of relief camps. Sreekumar told the DGP that the police should not be party to the forcible eviction of Muslim inmates of relief camps and the DGP agreed with him.

On June 7, 2002, the chief minister’s principal secretary, PK Mishra asked Sreekumar to find out which minister from the Modi cabinet had met a citizens’ enquiry tribunal (looking into the Godhra and post-Godhra violence) of which retired supreme court judge, VR Krishna Iyer, was a panel member. Mishra told Sreekumar that minister of state for revenue, Haren Pandya, was suspected to be the man concerned. He also gave Sreekumar the number of a mobile phone (No. 98240 30629) and asked him to trace details of this meeting through telephone records. On June 12, 2002, Mishra reiterated that Haren Pandya was believed to be the minister concerned. In his register, Sreekumar states that he had stressed that the matter was a sensitive one and outside the SIB’s charter of duties. Call details of the above mobile phone were however handed over to Mishra through IGP OP Mathur.

On June 25, 2002 the chief minister convened a meeting of senior officers to enforce the law according to their (Modi’s) reading of the situation. Sreekumar writes: "It is… unethical and illegal advice because the police department has to work as per law and not according to the political atmosphere prevailing in the state. He (Modi) also asked police not to be influenced by the Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) brand of secularism. The indirect thrust of the chief minister was that police officers should become committed to the policies of the ruling party so that law enforcement can be done smoothly."

Battle lines were further drawn on June 28, 2002 when at a meeting convened by the chief secretary, G. Subbarao, to discuss the chief minister’s proposed gaurav yatra (march of pride) in September, Sreekumar proposed that in light of the prevailing tension the annual Jagannath rath yatra in July 2002 should be cancelled. The CP, Ahmedabad, endorsed this view while a few others suggested a change in the parade route. The chief secretary then informed the group that there was no question of such a cancellation or even a change of route. After the meeting, the chief secretary took Sreekumar aside to tell him that anyone trying to disrupt the rath yatra should ‘be eliminated’, adding that this was ‘the well-considered decision of the chief minister’. Sreekumar told Subbarao that such an action would be totally illegal and unethical. The chief secretary maintained that it could be justified in terms of ‘situational logic’. Sreekumar replied that the police had to function in accordance with the law. The chief secretary then promptly watered down his request and asked Sreekumar to keep an eye on the plans of anti-social elements.

On July 1, 2002 Narendra Modi himself convened a meeting to review the law and order situation in view of the proposed gaurav yatra in September and the annual Jagannath rath yatra scheduled to take place that month. At this meeting Sreekumar provided intelligence inputs of ‘high voltage threats’ from pan-Islamic elements who would use such occasions and elicit support from those damaged and scarred by the recent violence. He advised that the rath yatra should be cancelled. His personal register notes: "The chief minister said that the rath yatra will not, repeat, will not, be cancelled." Eight days later, describing a follow-up meeting organised by the chief secretary on July 9, 2002 where precautionary measures were discussed, Sreekumar’s register entry states that "The chief secretary informed (the meeting) that anybody trying to disturb the rath yatra should be shot dead."

On August 6, 2002 DGP Chakravarti informed Sreekumar that the additional chief secretary (home), Ashok Narayan was not too happy with the data on communal incidents that the ADGP’s office had provided to the home department. In his register, Sreekumar writes: "I responded that my office has been providing correct information and the ADGP (int.)’s office cannot do any manipulation of data for safeguarding the political interests of the Narendra Modi government."

Sreekumar’s register notes that on August 5, 2002 the additional chief secretary had expressed his annoyance and displeasure at the SIB’s presentation of data on the communal situation. Narayan noted that it did not conform to LK Advani’s reply in parliament on the Gujarat question! He felt that every incident that occurred was being labelled a communal one, thus presenting a misleading picture of the law and order situation in Gujarat, especially to the Chief Election Commission (CEC). (This was the period when the Gujarat government was trying to push ahead with early assembly elections claiming that ‘normalcy’ had returned to the state and the CEC was due to visit Gujarat for an independent assessment.) Sreekumar asked Narayan to define the yardstick for assessment of affected areas but received no satisfactory response. The same afternoon, the home secretary, K. Nityanandam instructed the ADGP’s office that they should not send any data on communal incidents whereupon Sreekumar informed him that the data could not be manipulated to serve the interests of the Modi government. By this time it was evident that with elections around the corner the higher bureaucracy was apprehensive about any information that could embarrass the government.

On August 8, 2002, Ashok Narayan informed Sreekumar and others present that the next day (i.e. August 9) the election commission, consisting of chief election commissioner (CEC), James Lyngdoh, and two other members, would be holding a meeting which Sreekumar should also attend. The additional chief secretary also told Sreekumar that he "should not make any comments or presentation which would go against the formal presentation prepared by (home secretary) Shri K. Nityanandam". Sreekumar replied that he would "present the truth and my assessment based on facts".

On August 5, 2002 the additional chief secretary had expressed his annoyance and displeasure at the SIB’s presentation of data on the communal situation. Narayan noted that it did not conform to LK Advani’s reply in parliament on the Gujarat question!

At the time, the Gujarat bureaucracy had planned two presentations to be made before the CEC, one by the home secretary and another by the relief commissioner, CK Koshy. In an informal chat with his officers on August 9, 2002, chief secretary, G. Subbarao said that his men should present a picture of normalcy so that the CEC would have no reason to postpone the Gujarat elections. The CEC met the higher bureaucracy the same day. James Lyngdoh intervened at the start to say that he was not interested in presentations. The chief secretary carried on regardless, saying that "total normalcy was restored in the entire state and no tension was prevailing anywhere". Sounding both annoyed and incredulous, Lyngdoh observed that the commission had just visited affected areas where victims had made numerous complaints. He cited reports of a recently constructed wall barring right of passage to minority members in a particular locality of Ahmedabad. Undeterred, the chief secretary replied that rehabilitation was virtually complete and that most riot victims had returned home. A visibly angry Lyngdoh then asked the chief secretary how he had the ‘temerity to claim normalcy’ given the quantum and scale of the complaints. Lyngdoh insisted that the Gujarat government provide data along standard lines about the number of FIRs filed, the number of perpetrators arrested, the number of accused released on bail, the number of displaced persons, the compensation paid, and so on.

DGP K. Chakravarti then abruptly steered the discussion to the need for extra paramilitary forces during the forthcoming gaurav yatra. Sreekumar reiterated this point. Here, the CEC intervened to point out the contradiction between the chief secretary’s claims of normalcy and officers’ demands for additional forces. Lyngdoh then asked Sreekumar to elaborate on his claim for more forces. Sreekumar made his presentation (which included data on the number of deaths, property losses, the districts and villages affected and the overall plight of victims), arguing that tension still prevailed in 993 villages and 151 towns that had witnessed riots between February 27 and July 31, 2002. The affected area, he said, covered 284 police stations and 154 out of 182 assembly constituencies. On being asked to estimate the number of additional forces required, the DGP said that they would need at least 202 extra companies.

After all the other officers had left, the chief secretary summoned Sreekumar and shouted, "You have let us down badly! What was the need for you to project all those statistics about displaced people?" Sreekumar told him that he had presented the facts. Later, as Sreekumar was waiting for another meeting, additional chief secretary, Ashok Narayan came into the room along with the DGP and asked Sreekumar why he had made a statement contrary to the government’s ‘perception’. Narayan also asked Sreekumar whether as a disciplined officer he accepted the DGP’s authority. Sreekumar told him that the question was best answered by the DGP himself. Refraining from comment, the DGP (perhaps to avoid a confrontation) said that there was no point in pursuing the discussion. DGP Chakravarti later told Sreekumar that his assessment, particularly of manpower requirements, was accurate.

This was not all. On September 10, 2002, the National Commission for Minorities (NCM) faxed a message to the Gujarat home department requesting a verbatim copy of the chief minister’s speech made at Becharaji, a temple town in Mehsana district, on September 9, 2002. Modi’s hate speech formed part of the overall message of his gaurav yatra. Keen to block such information, the home department got the DGP to endorse that Sreekumar’s department, the ADGP (int.)’s office, was not required to provide such a report. Sreekumar, however, felt duty bound to comply with the request. Risking the wrath of his superiors, Sreekumar obtained a copy of the speech and forwarded this to the commission. Sreekumar’s action, his sending a copy of Modi’s speech to the NCM, was the proverbial last straw on the official camel’s back. He was immediately transferred from the post of ADGP (intelligence) and made ADGP (police reforms), a position empty of content.

Following protocol, Sreekumar then called on the chief secretary, G. Subbarao. The chief secretary told him that he should not have spoken up in contravention of state policy. Sreekumar responded that as a government functionary his oath was to the Constitution and "If the chief minister’s policies are in contravention of the letter, spirit and ethos of the Constitution of India, no government officer is bound to follow such policies." Visibly annoyed, the chief secretary brought the meeting to an abrupt end. RB Sreekumar’s personal register ends with this episode.

Archived from Communalism Combat, July 2007 Year 13 No.124, Genocide's Aftermath Part II, State Complicity 1