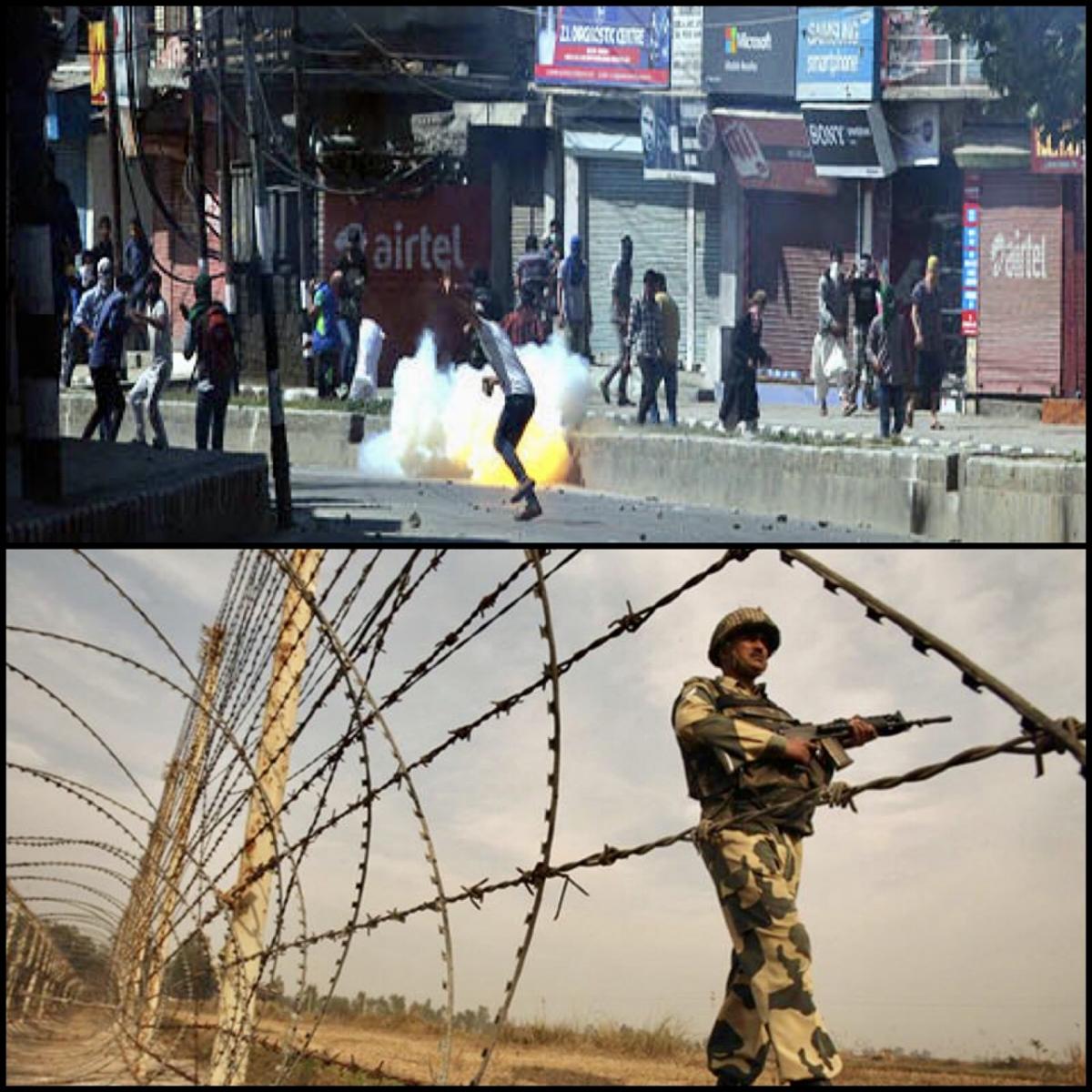

Image Courtesy: Greater Kashmir

Its been a year, harsh, hard and long since the killing of 22-year-old Hizbul Mujahideen Commander Burhan Wani on July 8, 2016 which sparked a massive uprising in Kashmir. The protestors, angry and disillusioned with the way India and its mechanisms have responded, are once again demanding the right to self-determination. At this crucial juncture for Kashmir, we interview Irfan Mehraj, a human rights worker who has witnessed the year-long protests unfold, first hand. Irfan Mehraj is a researcher at Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society.The interview was conducted by Rishabh Bajoria. [Internet services were 'officially' suspended on July 6-7. Any attempts to re-connect to Kashmit, today, July 8, have proven to be difficult: Sabrangindia)

Q. How would you look back at this one year in the context of Kashmir and the conflict within and without, particularly in the context of human rights?

The State’s (Indian) response towards people’s movement/ protests, many of whom aspire to the right to self-determination is getting increasingly violent. In the past year (from July 8, 2016), 170 civilians have lost their lives in the course of firing (by Indian security forces). People’s expressions of solidarity towards these expressions by the militants are being criminalised by the State. This does not leave people space to peacefully voice their grievances (with the State). The situation in Kashmir is getting more violent. The State is hand in glove with this because the State’s policy has been to crush rebellions with brute force. The State has been behaving this way in Kashmir for many years, but since 2016 it has become more brutal. Maybe the one difference was that Burhan Wani evoked such response from Kashmiris, that lakhs of people came out for his funeral. The State did not, or could not, pre-empt that this kind of response to Burhan’s death.

Q. What was it about Burhan Wani that his death caused such an outpouring of emotion?

There are multiple reasons. One of the reasons for his adored following was his obvious charm, visible through his presence on social media. He was very young, only 22 when he died. He had joined the militancy when he was only 16, but he had shown a maturity which I believe is often missing, especially in the rungs of the leadership of the present militancy. A lot of Kashmiris were attracted to it, because they saw him as a man who was challenging the Indian State with a narrative that was as clear as the ground reality within the Valley. He was therefore not only well known, but respected and loved by the people. He was successfully raising awareness about the movement. His success is evidenced by the number of people who attended his funeral, the number going into lakhs. His funeral was conducted 40 times in Tral alone. Imagine the rest of the valley! Also the collective expression for azadi or the right to self-determination in Kashmir had not seen much activity between 2001-2010. But since 2008 with the emergence of widespread people’s protests, it is this demand that has returned to the forefront.

I was travelling in a Sumo (the often used form of public transport in Kashmir) just this morning (Friday July 7) and the conversation among the passengers was how in the 1990s (widely considered the peak of Kashmiri militancy), the battle lines were not so clear. People were unclear about how to react when there is an encounter (extra judicial killing). Today it is like an all out, open war. Militants are engaging with the Indian State in an open battle, and ordinary people are coming out in support for them (militants). So, some of the Indian State’s façade, at least, over the Kashmiris being happy with the State is being wiped away because of the people’s response to the death of militants like Burhan Wani and Bashir Lashkari (LeT Commander). At least 20 people (ordinary civilians) have died because they were at the sites where they were killed, something which would not occur earlier.

Q. (cutting him off) Could you briefly explain to an Indian audience what a militant means to a Kashmiri?We increasingly see that ordinary, unarmed civilians are actively going to encounter sites to help militants escape. Is this a new phenomenon in Kashmir? If so, then what explains this?

The atrocities by the Indian State have been so rampant that the fear psychosis within the Kashmiri people has gone. That’s the main reason why people, especially in rural belts, come in droves to encounter sites and pelt stones at the Indian security forces to help militants escape. People are now ready to die with bullets at these ‘encounter sites’ rather than suffer silently.

One of the reasons such support is being shown to militants is because militants are now out in the open. In the early 1990s, conversations about militants were “hush-hush”. Now Kashmiri militants are out on social media and are constantly interacting with the people through audio/ video statements. Their faces are in the public space, and people know them. In the 1990s, while the numbers (of militants) was huge, they would live in hiding. People did not even know who the militant was. Now, if anybody becomes a militant, his whole village, and even the neighbouring village knows about it. For instance, before his killing, Burhan was an active militant for 6 long years. For the entire time, people were protecting him/ giving him shelter. This shows that Burhan’s presence among the people was completely accepted. Obviously, these are our own people. These are people who are coming from our ranks.

Another difference (between the current stage of militancy and 1990s) is that in the 1990s, the militancy was started purely as a political movement. It was not driven at the time by the large-scale human rights violations conducted by the Indian State against Kashmiris. Younger militants joining now are motivated by the brutalities of the State. For instance, people have joined militancy right after Burhan Wani was killed feeling that they cannot let the atrocities of the Indian State go without some response. The militants today are of the same1990s generation, like me. We have all seen the atrocities of Indian securities first hand. When you witness so much daily violence on such a large scale, the predominant, lasting feeling/conclusion is that there is no atmosphere for dialogue in Kashmir, even as far as the State Government is concerned. No breakthrough for politics in Kashmir.

Look at the Hurriyat — most of the time they are behind bars. These people (youth who join militancy) feel a deep sense of insecurity that the abuses against them are going unnoticed. Hence, they take up guns and announce to the world that Kashmir is experiencing a war-and that Kashmiris want an end to the Indian occupation, and you will have to listen to us. Since the 2016 uprising, there has been an exponential increase in the number of local militants. That tells you the kind of appeal Burhan Wani had among Kashmiris, and what influence his death had on a generation of Kashmiris.

Q. On political dialogue, do you think the All Party Delegation that went to Kashmir in September 2016 had a positive impact?

No, I do not think the delegation had any kind of impact. The first problem with the delegation is that the only people they (delegation) talk to are those who have no problem with the present status quo. The delegations have to talk to Hurriyat, but Hurriyat will not talk to them unless they have a certain kind of, discussed and accepted, agenda. Whenever there are tensions in Kashmir, when there is an uprising and people are demanding azadi, these all party delegations are sent to Kashmir to try and douse Kashmiri anger. By now, Hurriyat has understood that there is no use talking to such delegations.

On the 2016 Uprising and its impact

In my view, the 2016 uprising has not ended. I don’t know why journalists and political pundits are saying that it has ended. The only evidence to suggest that the uprising has ended is that Hurriyat has stopped giving calendars (which it issued since the beginning of the uprising).

However, the daily occurrence of violence has grown. Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society released a statement that the first few months of 2017, between January and March, have been the most violent in the last decade. Even in the holy month of Ramzan, the number of casualties was very high. We have not seen a Ramzan like that ever before.

I believe the 2016 uprising shook the Indian State to its core, and their response to it has been increasingly brutal, going all out-even their operation is called “All Out”!Another example of the increase in the brutality of violence since the 1990s is that in the 1990s, violence was perpetrated against Kashmiris in the form of extra-judicial killings, enforced disappearances, rapes and so on. Now, violence is being committed within the realm of the law.So, now there are a lot of administrative detentions, at least 15, 000 people were arrested in the course of 5-6 months.

Then, the post December-January student protest erupted. We have not seen this kind of student protests in Kashmir since the early 1990s. This wave of student protests was unprecedented. The reason for this protest erupting is that in the 6 months of brutality, these are students who have seen their classmates injured, blinded by pellets. A lot of people were injured/ arrested in these protests. So, nothing has changed in Kashmir since Burhan Wani’s killing. Daily violence continues. A whopping number of encounters have taken place in the last 6-7 months. In this atmosphere, the State machinery is not responding to the people’s just demands for freedom which Kashmiris have been articulating for a long time. Instead, the State is criminalising the articulation of this demand, and robbing the people of the space for voicing their claims. Unless the State provides this space, I think that the movement will get more violent. People will not cower down to State pressure. The 2016 uprising has led to a further increase in awareness, which was already high, about the need for resistance.

Q. On state brutality, pellet guns were introduced in Kashmir in 2010, but they came into focus during the 2016 uprising when around 1200 people were blinded as a result of pellet injuries. Do you see this as an increase in State brutality? What is the general sense of Kashmiris towards pellet guns?

Pellet guns are brutal. Even in 2010, a significant number of people lost their eyesight owing to pellet injuries. In 2016, pellet guns became the face of State violence against Kashmiris. Pellet guns represent the complete disregard for and dehumanisationof Kashmiri bodies, unapologetically blinding them, maiming and torturing them. In Kashmir, pellet guns are seen as symbol for the State being able to dehumanise and maim you with impunity. Therefore, there is a lot of anger towards pellet guns.

Q. How do we then understand the Indian State’s characterisation of the pellet gun as a non-lethal weapon despite the pellet gun causing so many injuries above waist height?

I don’t see the Indian State revising this characterisation. This is because, as the Army General of India admitted, the Indian State is at war in Kashmir. Both sides know that this is war. There is just a façade over it at the official level by painting protestors as misguided elements who must be dealt with accordingly. I think the categorisation of the pellet gun as a non-lethal weapon is just to confuse the international community and its own people (Indians). I think the war in Kashmir is also directed at people in India, to bolster support for Right-Wing Hindutva politics. That’s why the response of the State to the violence against minorities in India (Muslims, Dalits) is not very different.

Q. You earlier mentioned the personal touch militants are now able to have with the people through social media. Do you think social media has had a massive impact on the nature of the resistance movement?

No, I would say its tertiary. The resistance movement in Kashmir is not run by social media. In fact, social media is a representation of the sentiments of Kashmiris on the ground. For instance, after Burhan Wani was killed, the State snapped internet very soon after. Despite that, there were large processions consisting lakhs of people. So, how did they come on the road? They did not need social media to mobilise. Mobilisation in Kashmir can happen quickly through word of mouth. However, social media has helped change the nature of the militancy in Kashmir by facilitating the presence of militants in Kashmiri homes and helping make militancy increasingly acceptable in the public space. At best, it is a server of information and communication. People don’t need social media to mobilise, they are already doing it. Since last year, social media in Kashmir has been snapped 14 times. It has been cut off during encounters. However, people still come in hordes to encounter sites because people know where the militants are.

Q. The night before last(July 6) again internet services were cut off in Kashmir. What do you see this as symptomatic of? Why does the Indian State keep doing this if the presence/ absence of internet does not make a significant difference?

I think the Indian State is trying to experiment to see whether internet ban will work or not. So, last night while they cut off internet services, they have been back up since the morning. That could also be because today (July 7) is not as crucial as tomorrow. My sense is that later tonight they will shut all internet services. The order of the Government was to ban social media. But everybody knows that a couple of months ago when the State banned social media, the ban was unsuccessful because people used VPNs (Virtual Private Networks)/ proxies to circumvent the ban.

Q. Could you give us a brief account, from the ground, about what happened in the Valley post the news of Burhan’s killing?

As soon as news spread that Burhan had been murdered, people spontaneously mobilised. They came out onto the streets in anger. For instance, I think that in Srinagar alone there must have been 15-20 funerals for Burhan Wani. The protests started out as being relatively peaceful. On July 9, when the State imposed a curfew, people came out in droves to protest. Especially southern parts of Kashmir saw massive protests with widespread stone-pelting. This was met with violence by the State, at least 20 people were injured, out of which 12 died on the spot, while 8 died later on. In the first 5 days of the protest, nearly 50 people were killed in protests. This shows the brutality with which the State treats protestors. After such a violent State response, the uprising was inevitable. Nothing the State did could have prevented it. In Kashmir, you can’t come back from that. The initial shutdown call (by Hurriyat) was given for 3 days, but in those 3 days more people died. Then another shutdown call was given for 5 days, and in those 5 days more people died. Therefore, the violence becomes a cycle and that’s how the uprising snowballs.

Q. What happened after that for the next 6 months during the Hartal?

Right after Burhan Wani’s killing, Hurriyat gave a shutdown call for 3 days. In those days, more people were killed. So the call for shutdown was extended further. As more people kept getting killed, Hurriyat repeatedly kept extending its calls weekly. Then, after the first month, Hurriyat started giving calendars about the daily plans/ strategies about how to protest with the larger goal of achieving the right to self-determination. Between August-December 2016, there were close to 400 rallies held demanding Kashmir’s right to self-determination. Despite those rallies being peaceful, violence was used against those rallies as well killing 7-8 people. Often, even when people are trying to come out for peaceful rallies, the Police does not allow them. When the Police tries to stop them, the people respond with force, often as an expression of political dissent against State violence. Hundreds of people were blinded and arrested at these rallies. If the State would have allowed the peaceful rallies to proceed, the rallies would not have turned violent.

Q. Would you characterise the 6-month long shutdown/ Hartal as a success in making the Indian State listen to Kashmiris?

I would say that it was a success in making the Indian State listen. However, a complete shutdown for 6 months where all economic activity has ground to a halt does take an economic toll on people. I think Hurriyat’s call (post December to stop the official shutdown) was to try and ease this economic pain, to allow people to go back to their economic lives and try to recover what we can, while continuing the resistance through protests. For instance, student protests erupted after January 2017.

Q. On a social level, how do Kashmiris cope with such extended shutdowns? For instance, how do they manage food, supplies, etc.?

Something that baffles both the Indian State and Indians is that because Kashmiris have known so much tragedy, for instance, we have been experiencing long curfews since the 1970s, Kashmiris have a tradition of stocking up on food supplies such as rice, lentils, etc. for 3-6 months. Due to the harsh winters in Kashmir, they are used to stocking up. But gradually this habit has extended to the summers as well because Kashmiris never know haalat ka kya hoga (what will happen, when the situation may worsen). So, the reason for stocking up has changed from a climatic one to a political and cultural one.

Q. Going back to a political level, how do you read Mr Khurram Parvez’s detention by the Indian State?

I think Khurram was detained to deter Kashmiris from daring to criticise the State. Khurram is a global figure who has worked tirelessly in the field of human rights activism. When the State arrests somebody like that, it is sending out a signal to all those people who are willing to be critical of the State that we are coming after you, and nobody is off limits, so we can do anything. Khurram’s detention was also an attack on his work as a civil rights activist, because JKCCS (of which Khurram Parvez is the program Coordinator) is still doing human rights work from the ground level despite there being an active uprising in Kashmir. So, when you arrest Khurram, a lot of the energies of the organisation goes in getting Khurram released.

The State, in addition to arresting Khurram, also arrested several lawyers and academicians to deter people from daring to criticise the State. The most important reason was that the State wants to raise the cost of dissenting against it. That is also why we see a rise in State brutality against protests, because such brutality raises the cost of protesting. But, instead of deterring people, this tactic is backfiring because Kashmiris have lost all sense of fear (of even death).

Q. In the backdrop of what you just described, how do you see things unfolding from July 8 in the Valley?

I fear for Kashmiri lives, and hope that more lives are not lost. My sense is that there will be a complete crackdown in the public space to ensure that the 2016 uprising does not repeat itself. People will want to come out and protest. The next two or three days are crucial, especially areas south of Srinagar such as Phulgama, Anantanag, Sopore, and so on because I think that people will want to head towards Burhan Wani’s ancestral home in Tral. Already the State has blocked all routes to Tral. So, the State has already taken preventive to prevent people from going to Tral. Again the State is dealing with these situations how it always does, with an iron hand through the military by preventing people from expressing solidarity with the militant’s family. That is precisely the kind of action that prompts ordinary people to resort to violence, because you are not allowing people to mourn.

(The person conducting the interview is a student of the Jindal Global Law School)