Is government-sponsored education system in West Bengal on the verge of extinction? According to sources, student enrolment has decreased by 35% in primary and 42% in upper primary (class 5-8) schools in the current academic year.

Most children from poor and marginalised families study in these government-aided schools. In fact, a large number of school-going children from families living in the worsening socio-economic situation are not entering the field of education.

The point is that education for the poor has reached rock bottom. What will be the consequences of this state of affairs?

The state government’s apathetic attitude toward education has created an atmosphere of fear. Not only the general public and guardians, but also officials in state and Union ministries discussed the education scenario in West Bengal at the end of April 2025. Both sides reportedly expressed “deep” concern over the dwindling number of students at the primary and upper primary levels.

The Basis for ‘Deep’ Concern

The number of mid-day meals that students partake is being considered a criterion at the government level. The decline in the number of students receiving mid-day-meals is a picture of decline among students in government-sponsored primary and upper primary schools. Students of both these levels receive mid-day meals.

In addition, parents seem reluctant to admit their children to government schools. Although there are exceptions, but this is broadly a state phenomenon, several school teachers this writer spoke to, said. Why?

During the last Left Front regime in Bengal from 2006-2011, about 50,000 teachers and non-teaching staff were recruited through specific examination (District Primary School Councils took the exam for primary teachers, and four regional School Service Commissions arranged for high and higher secondary teachers and non-teaching staff). A large portion of these recruitments were of primary school teachers.

“ The district primary school councils used to recruit teachers through examinations within a specific period of time”, Jyansankar Mitra, former Chairman of Bankura District Primary School Council, told this writer.

“The West Bengal School Service Commission (WBSSC) was constituted in November 1997 under the West Bengal School Service Commission Act. The Act was enacted on April 1, 1997, and came into effect on the same day. The Commission is responsible for recruiting teaching and non-teaching staff in government- aided schools in West Bengal. Since then, teachers have been recruited to high and higher secondary schools through examination almost every year” said Professor Biswanath Koyal, first Chairman of Western Zone of WBSSC, whose jurisdiction was Bankura, Purulia, undivided Pashchim Medinipur, and Purbo Medinipur.

According to the Right to Education Act 2009, the Ideal student-teacher ratio should be 30: 1. In 2008, this ratio was 35: 1

Biman Patra, district secretary of All Bengal Primary Teacher Association, Bankura district committee, the largest primary teachers’ organisation of Bengal and Panab Mahato, his counterpart in Purulia, said due to the severe shortage of teachers, the current ratio had risen to 70:1.

After the Trinamool Congress came to power in 2011, the government recruited primary teachers in 2014 and 2016. There are allegations of widespread corruption in recruitment of those who were appointed in 2017 after the 2016 exams. The matter is sub judice in the Calcutta High Court.

As of now, the jobs of over 32,000 primary teachers are hanging in uncertainty. Significantly, On April 3, the Supreme Court, having reached the conclusion that there was multiple corruption in the recruitment of teachers and non-teaching staff in high and higher secondary schools through WBSSC in 2016, cancelled the entire panel. As a result, 25,752 teachers and non-teaching staff lost their jobs.

There are similar allegations in the primary recruitment sector. In fact, many schools do not have enough teachers against the requirement. On the other side, a large portion of those who are in teaching positions are uncertain about the continuity of their jobs.

“Overall, it can be said that there has been an institutional crisis in the education sector in the state. This is having a devastating impact on students, teachers and parents in the area”, Panab Hazra, a librarian at Sidhu-Kanhu University of Purulia and Subikash Choudhury, former head of the department of economics, Bankura Christian College, told this writer.

“Despite financial difficulty, I have admitted my son to a private school, because I do not know when the government schools will close. The teachers are not adequate. I do not know if those who are there, will continue”, said Mainuddin Mandal, a bread hawker in Vhikurdihi village of Bankura district. He hawks bread brough from Chandigarh in Punjab.

His wife, Rehena Bibi, said “We are struggling to run our family only for our children’s future. We have to somehow survive. We spend Rs 3,000 a month (in a private school) for my child in Class 4.” She said many parents were opting for this instead of government schools for the future of their children.

In Bagmundi area of Purulia district, this writer met a migrant worker, Ramesh Sardar. When asked, he said, “What will happen if my son completes his schooling? Will he get a job? Is there any job here? Several educated youths are sitting idle, counting their days. They are highly frustrated.”

He said he had admitted his son, Bachhu, in a high school. He studied up to Class 7. “There is only one teacher, how can this teacher manage four classes? What will students learn? Nothing. It is better to learn some manual labour skill from an adolescent age and find work in other states. At least, he will be able to eat and survive, and look after the family in the near future”.

A few days ago, some male and female agricultural labourers, along with their school- going children from Bankura, Purulia and Jhargram districts, were seen waiting at the Bankura bus stand under the scorching sun for buses to return home after harvesting boro paddy from various villages in Hooghly and East and West Bardhaman districts.

“There is no work in the area, matikatar kaj (MGNREGA work) has been closed for four years, and panchayats do not respond regarding our work. We have to survive somehow, so we go wherever we find work. Who do we leave our sons and daughters with? So, we take them along,” Urmila Lohar from Tilaboni village in Purulia, said.

When asked, all of them said that “education of our children are no longer on our minds. We have to survive first, then study.”

“This painful picture is common among jobless poor and marginalised families across West Bengal”, said Amiya Patra, leader of the Khetmajur Union and Sagar Badyakar, assistant secretary of the union’s Bengal unit.

Teachers Trying Hard to Bring Children to School

During the Left Front regime, there was a Village Education Committee (VEC) in every area. That committee consisted of an elected representative from the local panchayat/municipality, a member of the Opposition party, ICDS (Integrated Child Development Scheme) workers, an education expert of the area and teachers. The committee would discuss the ongoing situation of education in the area and take necessary measures.

“After the Trinamool Congress came to power, that VEC was dissolved. There is no discussion on education issues of the area even in the education standing committee at the block level. Only one meeting is held a year, that too related to school annual sports,” said Patra.

Rupak Mondal, district secretary of ABPTA, Jhargram district, along with several male and female teachers from Bankura, Purulia and Jhargram, confirmed that the two years of school closure during the Covid pandemic was still having a major impact. In families, where children did not attend school after it re-opened in 2022, the younger brothers and sisters have been following suit. Many of them have left government schools and have enrolled in private ones. That trend is continuing.

It is a fact there is severe shortage of teachers as well as of officials in the education department, who are responsible to monitor the condition of schools. In this situation, several teachers have been visiting the homes of villagers and are trying to bring their children back to school.

“We go to different houses in the village and look for expectant mothers. We tell them in advance that when the child is born, he/she should be admitted to our government school. We observed that if a child takes admission in a private school his/her brother and sister will follow that path. But the fact is that in many families, the youth are not getting married because they don’t have jobs. As a result, the number of child births is decreasing” said Amit Goswami, headmaster of Kenjakura Primary school. Bankura.

“There is reluctance among parents to admit their children to government schools. The shortage of teachers is a big reason. Child birth is also decreasing in remote areas. We have asked the government to think deeply about this issue and take proper needful measures”, said Tuhin Banerjee, a primary teacher in Dubraji village of Bankura and district leader of Trinamool’s Shikhsha cell.

The District Information System of Education (DISE), which records all information regarding a school, according to the RTE Act, regarding meeting of specific criteria or if an educational institute is not given the DISE code number. During the Left Front regime, private schools did not get that code. Now it is being given to private schools in large numbers. As a result, the number of private schools is increasing.

Despite struggling to support their families, many low-income people are sending their kids to private schools, which has turned into a status symbol, said several teachers and guardians. Many parents also complained that the syllabus of government schools was not “good” and “up to date”. Also, there are fewer teachers in government schools.

On the other hand, private schools offer opportunities to study many subjects, including computers. Several parents feel this is one the key reasons for low enrolment in government schools.

Significantly, many government school teachers also are admitting their children to private schools. This is also having an impact on the people’s mind. As a result, students from financially backward families study in private schools till the primary level, but when they enter high school, they face problems in adapting to the environment. Not all families are able to afford the high cost of private education. Hence, many are forced to drop out midway.

Situation in Upper Primary Schools

Upper primary schools were built during the Left Front regime considering the geographical location of the area so that children do not have to go to high schools located far away to study from Class 5. They could study in the local area up to Class 8. After reaching Class 9, the boys and girls could travel to a distant high school.

“The Madhyamik Shiksha Kendra (MSK) that are built for grades five to eight are provided with adequate teachers”, said Fatik Goswami, former headmaster of Radhamadhab Madhyamik Shiksha Kendra of Kumidya village in Bankura. After TMC came to power, new teachers were not appointed in upper primary schools. As a result, the number of students kept decreasing.

Six MSKs have already been closed in Ranibandh of Bankura district. On January 7 this year, the Bankura district administration issued an order for shutdown of seven more MSKs. This includes Kumidya Radhamadhab MSK School.

“Had the government appointed adequate teachers in this school, students would have continued their education”, lamented Mrityunjoy Banerjee, headmaster of the school. He and a teacher, Ramsankar Patra, appealed for saving the school at any cost.

“There have been no adequate teachers for years. How can we send our children to a school that lacks educators? Many have already dropped out,” said Bulu Dasmohonto of Kumidya village.

The newly established upper primary schools, which are called new set-ups, do not have the necessary number of teachers. Therefore, the number of student admissions is low, said a teacher in-charge of a newly set up a girls school in Indpur block.

Several guardians said after studying there were no job opportunities here. Several boys who studied in upper primary are already realising this and have dropped out of school to try other jobs. Several are already registered as migrant labourers.

Number of Students Taking Mid-Day-Meals

To meet the nutritional needs of students, the Left Front government in West Bengal was among the first to introduce mid-day meals in the country in primary and upper primary levels. Later, it was introduced across the country. In this context, the number of students receiving mid-day meals has become a definitive indicator of enrolment. During Left Front rule, in the 2010-11 academic year, 72,40,341 students received mid-day meals. After 14 years under the TMC regime, only 46,83,053 students are receiving mid-day meals. This indicates a decline of 26,57,288 students in primary education — a 35% decrease compared with 2010-11.

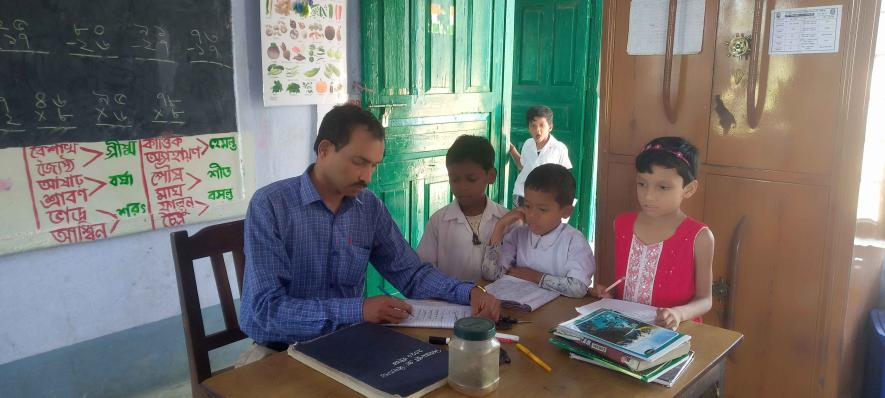

The number of students has dramatically decreased at Shibarampur Primary School in Bankura .

The situation is even worse at the upper primary level. In the last academic year, 40,41,666 students were admitted to upper primary in the state. As per state government figures, 23,66,232 students are receiving mid-day meals in upper primary schools. This means enrolment at the upper primary level has decreased by 42%.

When asked, Jagabandhu Banerjee, the District Inspector of School, admitted that the number of students admitted to primary schools had decreased. A section of people was moving to urban areas, he said, adding that therefore, the number of students in villages was decreasing. Efforts are being made to solve this crisis, he added.

The writer covers the Jangalmahal region for ‘Ganashakti’ newspaper in West Bengal.

(All pictures by Madhu Sudan Chatterjee)

Courtesy: Newsclick