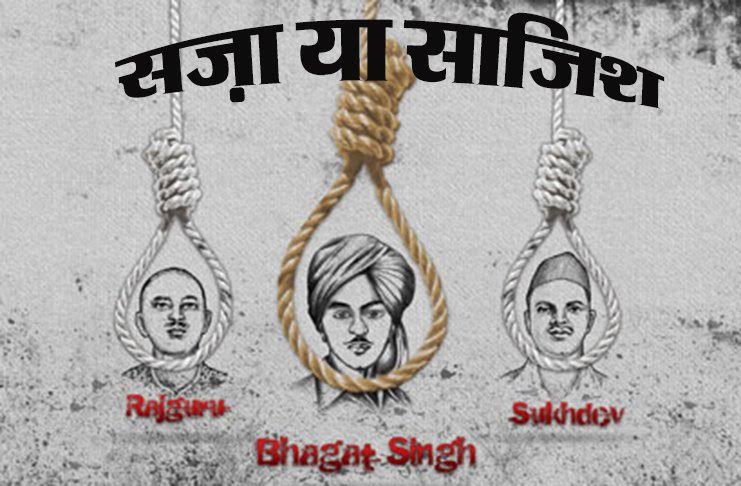

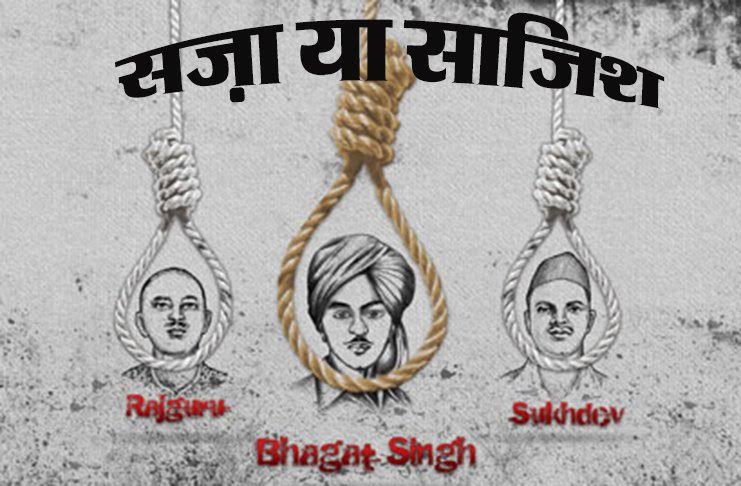

The British hanged them once, Indian Rulers hang them everyday

Bhagat Singh iss baar naa lenaa kayaa bharat-vaasee kee,

Desh-bhakti ke liye aaj bhee sazaa milegee phansi kee

Bhagat Singh don’t take birth as Indian next time,

You will again be hanged for the crime of patriotism.

[From Shankar Shailendra’s long Hindi poem of 1948]

On March 23, 2017, we will be commemorating the 86th year of the great martyrdom of the three revolutionaries, Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev. However, with every passing year, a sadness engulfs us because, as far as the mainstream political set-up is concerned, their sacrifices attract only ceremonial attention, and that too, occasionally. Indian democracy despite being seven decades old has missed the two most important aspects of their sacrifice.

Firstly, why were they hanged? The colonial masters did not hang them only because these three revolutionaries were trouble-makers like any other ordinary convict but had put them to the gallows because the British rulers were scared of their spreading the ideas of justice, and transformative change, and independence as championed by these martyrs.

The then rulers erroneously believed that by killing individuals, ideas too could be killed.

Secondly, these revolutionaries did not appear in isolation, nor were their sacrifices individual actions. These sacrifices that we commemorate on March 23, 1931 were part of a chain of sacrifices of revolutionaries who discarding the tag of ‘the terrorist’ had become the protagonists of a revolution with mass participation. Starting with the the Kakori Martyrs (1927) they had declared that they were fighting and sacrificing themselves on the altar of a new India where socialism will prevail.

A Socialist India

Ashfaqullah Khan, one of the Kakori Martyrs (martyred on December 19, 1927 at Faizabad, UP) and a great friend of Bhagat Singh, was the first revolutionary who clearly talked about a socialist India. Barely a few days before his hanging, in an open letter to the youth of the country, he lauded fellow communist activists in the following words:

“I have deep respect for you in my heart and I am totally in agreement with your objective while dying for the country. I wish that kind of free India where poor would live happily and fully satisfied. I hope that day would come soon when at Chattar Manzil (haveli/abode of an Avadh landlord), Abdullah, loco-workshop fitter and Dhaniya, a Jatav farmer would sit on chairs across Mr. Khaliq-uz-Zaman, Jagat Narain Mulla and Raja Mehmoddabad [sic].”

Bhagat Singh writing to ‘Young Political Workers’ (February 2, 1931) from jail emphasised the socialist path of the revolution in the following words:

“You chant, ‘Long Live Revolution.’ Let me assume that you really mean it. According to our definition of the term, as stated in our statement in the Assembly Bomb Case, revolution means the complete overthrow of the existing social order and its replacement with the socialist order.”

Bhagat Singh representing the feelings of his comrades about failure of the Congress-led freedom movement made the following point which proved to be prophetic:

“This [Congress-led] is a struggle dependent upon the middle-class shopkeepers and a few capitalists. Both these, and particularly the latter, can never dare to risk its property or possessions in any struggle. The real revolutionary armies are in the villages and in factories, the peasantry and the labourers. But our bourgeois leaders do not and cannot dare to tackle them. The sleeping lion once awakened from its slumber shall become irresistible even after the achievement of what our leaders aim at.“That is why I say they never meant a complete revolution. Through economic and administrative pressure, they hoped to get a few more reforms, a few more concessions for the Indian capitalists. That is why I say that this movement is doomed to die, may be after some sort of compromise or even without.”

Bhagat Singh rejected a free India where there would be a simple change of set of rulers; Brown rulers replacing White rulers: “What difference does it make to them whether Lord Reading is the head of the Indian government or Sir Purshotamdas Thakordas? What difference for a peasant if Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru replaces a Lord Irwin!”

Against Casteism and Untouchability

These revolutionaries lamented the fact that leaders who wanted political freedom from the British, were neck deep in practising untouchability and casteism. While strongly repudiating the regime of casteism and denigration of untouchables (June 1928), Bhagat Singh wrote:

“No other country will have such degenerated life as we have in India. A big question is about the status of untouchables. 6 crores out of 30 crores of Indian population are described as untouchables, if one touches them, religion is polluted. If they go to temples, gods get angry and if they draw water from a well, latter gets polluted… Just imagine, a dog can sit in our laps, can roam around in kitchen but if one untouchable touches you then religion is destroyed. Great social reformer like Madan Mohan Malviya, great fan of untouchables and what not, if is garlanded by a Valmiki, goes to take bath with his clothes to purify himself of the touch of an untouchable!”

Bhagat Singh was forthright in telling the victims of untouchability that practitioners of this dehumanized system cannot be reformed, the latter will have to be taught a lesson and called upon the untouchables,

“(to) get organized, stand on your feet, challenge the whole society. You will see that nobody will dare to deny basic right to you. Do not become a commodity for use and throw. Do not wait that others will come and liberate you… You are the real worker, you must get organized. You have nothing to lose but your chains. Come on! Rise in revolt against the present system. Nothing will be achieved by one or two reforms. Fight for a social revolution and advance to bring about social and economic revolution. You are the pillars of society, its real force. Rise up! sleeping lions, born rebels, bring about revolution”.

Against Communal Politics

Bhagat Singh and his comrades, who gave a new socialist ideological direction to the anti-imperialist struggle were highly conscious of the pitfall which communal divide presented. Bhagat Singh as an ideologue of the revolutionary movement and his comrade Bhagwati Charan Vohra (martyred on May 28, 1930) did not mince words while warning that the communal conflicts would completely destroy the nation. In a landmark document (‘Manifesto of Naujawan Bharat Sabha’ 1928), which they jointly wrote for the youth of India and was circulated widely in the country, the crucial fact was emphasized that,

“Religious superstition and communalism are great hindrance in our path of progress [freedom]. We must uproot these… Foreign rulers take full advantage of conservatism and reactionary policies of Hindus and narrow-mindedness of Muslims and all other communities. In order to accomplish this task [of freedom of the country] we need youth of all religions who are filled with revolutionary zeal.”

They equated communalism with mental slavery and said: “Unless we come together after getting rid of our narrow-mindedness there cannot be unity in real sense amongst us. We can advance on the path to freedom only after achieving unity. By freedom we do not mean only liberation from the clutches of the British but that complete freedom when people will stand united free from mental slavery.”

Earlier Ashfaqullah Khan had warned his country-fellows, both Hindus and Muslims, about communal bickering in the following words:

“Brothers! Your civil war, your internal bickering will not be useful for any of you. This is impossible that 7 crores Muslims can be converted to Hinduism [through Shuddhi] and likewise it is futile to believe that 22 crores Hindus can be turned into Muslims. However, [if they continue fighting with each other] it is easy and very easy that all of them together will continue to be in chains.”

This raw commitment to communal harmony and unity against imperialism could be seen manifest in 1940 also. Udham Singh who as a child was witness to the horrible Jallianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar of Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs on the fateful Baisakhi day of 1919 and had since vowed to take revenge, finally, succeeded 21 years later. After killing Miachael O’Dyer (the ex-Governor of Punjab and one of the high officials responsible for the Jallianwala Bagh tragedy) in London on 13 March 1940, when Udham Singh was produced before magistrates, he identified himself not as Udham Singh but as ‘Mohammed Singh Azad’, a combination of Muslim-Sikh-Hindu names.

Bhagat Singh the AtheistBhagat Singh was the finest representative of the politics of atheism. He as a fearless revolutionary stood for scientific thinking. He wrote an amazing essay ‘Why I am an Atheist’ in 1931 when his death warrant had been issued. This essay is believed to be one of the finest ever written in support of atheism not only in India but world-over. He challenged the existence of God in the following words:

“I ask why your omnipotent God does not stop every man when he is committing any sin or offence? He can do it quite easily. Why did he not kill warlords or kill the fury of war in them and thus avoid the catastrophe hurled down on the head of humanity by the Great War? Why does he not just produce a certain sentiment in the mind of the British people to liberate India? Why does he not infuse the altruistic enthusiasm in the hearts of all capitalists to forego their rights of personal possessions of means of production and thus redeem the whole labouring community, nay, the whole human society, from the bondage of capitalism?”

IntellectualsThese revolutionaries were led by patriotic romanticism which had solid theoretical basis. They spent times in jails studying political, social and literary tomes from India and abroad in order to have best possible knowledge for carving out correct strategy for Indian revolution. This zeal for knowing truth can be understood by going through the following letter of Bhagat Singh which he wrote to a comrade outside. It shows he wanted books not only for himself but all other comrades in different jails.

“Lahore Central Jail

24.7.1930My Dear Jaidev,

Please take following books in my name from Dwarkadas Library [Lahore now at Chandigarh] and send them through Kulvir [younger brother] on Sunday:

Militarism (Kari Liebknecht) Why Men Fight (B. Russel)

Soviets at Work, Collapse of the Second International,

Left-Wing Communism, Mutual Aid (Prince Kropotkin)

Fields, Factories and Workshops, Civil War in France (Marx)

Land Revolution in Russia, Spy (Upton Sinclair)

Please send one more book from Punjab Public Library: Historical Materialism (Bukharin). Also, please find out from the librarian if some books have been sent to Borstal Jail. They are facing a terrible famine of books. They had sent a list of books through Sukhdev's brother Jaidev. They have not received any book till now. In case they have no list, then please ask Lala Firoz Chand to send some interesting books of his choice. The books must reach them before I go there on this Sunday. This work is a must. Please keep this in mind.

Also, send Punjab Peasants in Prosperity and Debt by Darling and 2 or 3 books of this type for Dr. Alam. Hope you will excuse me for this trouble. I promise I will not trouble you in future. Please remember me to all my friends and convey my respect to Lajjawati. I am sure if Dutt's sister came she will not forget to see me.”

That the post-Independence Indian rulers were going to betray this revolutionary heritage was made clear as early as 1950. The cases of Bhagat Singh and his comrades were handled by senior police officers of Punjab during the British rule. These were the officers who tortured these revolutionaries and sent many of them to gallows. How Congress government of Punjab and India’s first home minister, Sardar Patel dealt with them is a shameful story. The following two letters exchanged between Punjab government led by Gopichand Bhargava and Patel are testimony to this shameful betrayal. Bhargava in a letter to Patel, defending the criminal police officers wrote:

“During the national movement of 1942, a large number of political workers were subjected to torture and indignities by some police officers, when they were detained or imprisoned for their political views in the camps jails, jails, forts etc. There were some leaders of all-India fame in the Lahore Fort and they were also subjected to inhuman treatment by some junior police officers in joint Punjab under the orders of their senior British officers. A few of these Indian officers are now in service with us. The torture, in most cases, consisted of interrogation under conditions where food was unwholesome, the detenus were kept awake or they were kept in unhygienic surroundings and in a few cases, they were given slaps or fist blows. There has naturally been some resentment against such officers and question has arisen whether any action should now be taken against such officers in the services.

“We had this matter under consideration for some time. These Government servants were members of a disciplined force and as such they were bound to carry out the orders of their superior officers. The alternative for them would have been dismissal or consequences more serious than dismissal. We feel that a question of principle is involved also. Supposing, today some police officers in their zeal to suppress the activities of some Communists take action against them under the orders of their superior officers and at some future time men of this party come into power, would they be justified in taking action against these officers if they are still in service at the time? Government servants, we consider, have to serve the Government of the day and carry out their orders. Such government servants are now as loyal and faithful as they were to their Britishmasters some years ago…” [Letter of Gopichand Bhargava, Premier of Punjab 1947-51 to Home Minister of India, Sardar Patel dated February 9, 1950, cited in V. Shankar (ed.), Sardar Patel: Select Correspondence 1945-50, vol. 2, Navjivan Publishing House, Ahmedabad, 1977, pp. 461-62.]

Responding to this letter, Sardar Patel informed Bhargava:

“Our whole outlook since Indian Independence has been based on ‘forget and forgive’ and in the cases which you have mentioned, I think we must proceed on the basis of forgiveness. I therefore, agree with you that the matter may be dropped”.[Letter of Home Minister of India, Sardar Patel, to Gopichand Bhargava, Premier of Punjab 1947-51 dated February 14, 1950, cited in V. Shankar (ed.), Sardar Patel: Select Correspondence 1945-50, vol. 2, Navjivan Publishing House, Ahmedabad, 1977, p. 462.]

It is not insignificant that Bhargava completely skipped the issue of extreme torture of revolutionaries and the hanging of Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev by the same kind of officers for the obvious reason that he did not want this issue to become an emotive one. But the intention of the Congress rulers including Patel was to side with the ‘killers’ and not the martyrs.

Today's latter-day Hindutva rulers who claim to be the great fans of Patel keep mum on this issue as they remained indifferent to the anti-colonial fight of these revolutionaries. The pre-Independence archives of the Hindutva organizations have absolutely no reference regarding the struggle and sacrifices of these revolutionaries. In fact, the most important ideologue of the RSS, MS Golwalkar who led the organization since 1940 denigrated the tradition of martyrdom in the following words:

“There is no doubt that such man who embrace martyrdom are great heroes and their philosophy too is pre-eminently manly. They are far above the average men who meekly submit to fate and remain in fear and inaction. All the same, such persons are not held up as ideals in our society. We have not looked upon their martyrdom as the highest point of greatness to which men should aspire. For, after all, they failed in achieving their ideal, and failure implies some fatal flaw in them.”

That the British, afraid of the growing popularity of the ideas of the revolutionaries, to stop them, put the revolutionaries to death on the gallows, is understandable. But the attitude of the Brown Sahebs who replaced the British rulers on August 15, 1947 towards the legacy of these martyrs is both shocking and reprehensible.

The fact is that the colonial masters hanged Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev in 1931, but the rulers of Independent India have been condemning to oblivion the ideas they lived and died for, shamelessly for decades. It is all Indians, imbibed with the anti-colonial and patriotic legacy of these martyrs, that will keep the dreams of these martyrs alive.

Long Live the Revolution!