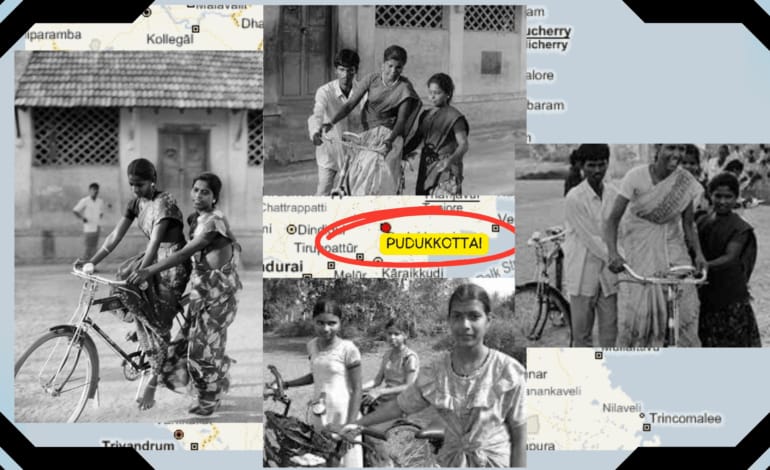

Strange are the ways that people find to make life better and battle adversities. Often, every person in every society camouflages multiple layers that might be impervious to others but have played a role in improving their station. Such is the story of the women of Pudukkottai who advanced beyond their confines.

Reading P. Sainath’s article, “Where there is a wheel” in the book “Everybody loves a good drought”, which narrated how the women of Pudukkottai were trying to cycle their way to personal independence, I felt a compelling urge to learn about the present condition of that place and its women. That’s why I headed to Pudukkottai, nearly 25 years after the master of rural reporting in India did so.

This is what Sainath had written about the cycling movement in Pudukkottai: “Cycling as a social movement? Sounds far-fetched. Perhaps. But not all that far -– not to tens of thousands of neo-literate rural women in Pudukkottai district of Tamil Nadu. People find ways, sometimes curious ones, of hitting out at their backwardness, of expressing defiance, of hammering at the fetters that hold them.”

He has also discussed how young Muslim women from conservative backgrounds enlisted themselves to learn cycling. In the heart of rural Pudukkottai, young Muslim women from highly conservative backgrounds zip along the roads on their bicycles. Some seem to have abandoned the veil for the wheel. Jameela Bibi told the journalist: “It’s my right. We can go anywhere. Now I don’t have to wait for a bus. I know people made dirty remarks when I started cycling, but I paid no attention.”

It was the then collector, Sheela Rani Chunkath, who had hit upon the idea to reinvent “the wheel” for the women of Pudukkottai. Cycling fever gripped the land through a literacy programme called Arivoli Iyakkam (Light of Knowledge Movement). “Cycling has swept across this district. Women agricultural workers, quarry labourers and village health nurses are among its fans. Joining the rush are balwadi and anganwadi workers, gem-cutters and school teachers. And gram sevikas and mid-day meal workers are not far behind. The vast majority are those who have just become literate. The district’s vigorous literacy drive, led by Arivoli Iyakkam, has been quick to tap this energy.”

Kannammal, Arivoli central coordinator, had told Sainath then: “The main thing was the confidence it gave women. Very importantly, it reduced their dependence on men. Now we often see a woman doing a four-kilometre stretch on her cycle to collect water, sometimes with her children. Even carting provisions from other places can be done on their own. But, believe me, women had to put up with vicious attacks on their character when this began. So many made filthy remarks. But Arivoli gave cycling social sanction. So women took to it.”

Kannammal was among those first off the blocks. Initially, she was not sure whether should would be able to ride a cycle while she is clad in a sari. But the would-be cyclists turned up in strength at Kilakuruchi village and the inhibitions fell by the wayside — as did several male-enforced barriers.

Even ballads were written about the cycle movement, prompting the women to sing aloud while they cycled in the village-

“Cast off these illusions/ Set fire to the misery they have brought upon you.

Like birds whose wings have been clipped,/ Society has kept you confined within your homes.

Emerge like a storm gathering its strength. O, sister, learn to ride the bicycle/ and then set forth on a journey on the wheels of time.”

This song, written by Pudukkottai poets Jayachandar and Muthu Bhaskaran, was one among the many that were written to inspire the cycling women.

The first girl I met after arriving in Pudukkottai was Karthika, 20, a bearer at the hotel I stayed at. After completing her Plus Two, she had enrolled herself in a degree correspondence course. Asked about bicycles, she appeared to wonder why I was even asking — she has been riding a bicycle everywhere since childhood.

“Now, I have an old cycle. The government gave me a new one but my father sold it. He had some debts to pay off. Now I need to buy a new bicycle. I’m saving a little from my salary,” Karthika said.

A whisper of a smile greeted the question whether she knew about the changes cycles had brought to the women of Pudukkottai. As her mother and the other women in her family had already been cycling ever since she could remember, Karthika said, it never felt like something worthy of special attention.

A middle-aged diner at the next table cut in: “All that is history. The younger generation today doesn’t know much about it. You should go out to the road and see for yourself.”

I did as the diner, Gopalan who runs a business, told me and stepped out. Gopalan was not exaggerating: I could see for myself women who were basking in the freedom of movement. The town was humming — with the bustle of girls galore, college girls and school girls riding bicycles.

The bicycle trail led me to the Annavasal Panchayat Union Office, where section officer Ilavarasi Vasanthan spoke of how bicycles had transformed the lives of women.

“Now the women of Pudukkottai are just like those in any other place. They venture out to do anything. The old way — where men would speak outside while women stayed at home — is gone. In the panchayat office and elsewhere, they come directly to ask questions and get things done. They’ve shown strength both in their families and in society. Most important, they continue to travel by bicycle.”

I recalled what Sainath had written once: “Never before coming to Pudukkottai had I seen this humble vehicle in that light -– the bicycle as a metaphor for freedom.”

Kannammal had told him that for women, cycling “is a Himalayan achievement, like flying an aeroplane”.

Around 30 years ago, the women of Pudukkottai were usually confined to the kitchen whenever guests visited. Arivoli Iyakkam, the literacy campaign, brought about some change: men eagerly attended the literacy classes but women still stayed indoors.

The then collector, Sheela Rani Chunkath, realised that the women needed to step out of their homes in order to take part in the literacy initiative. Among the many strategies she devised, one was teaching women to ride bicycles.

The Arivoli Movement cast cycling as a symbol of freedom, self-respect and mobility. Spearheaded by the collector, several programmes were implemented to encourage women to learn cycling, prompting thousands to take a shot at pedalling. It would be fair to say that the women of Pudukkottai literally cycled their way out of the kitchen.

In order to understand how the dramatic transformation took place, I tried to meet the women who had learned cycling then, as well as those who had worked with the Arivoli Movement at that time.

Pandian, who had volunteered with Arivoli Iyakkam when it launched its literacy drive in 1991, shared his experience. He recalled the days when women hardly stepped out of their homes and how the volunteers tried to reach out and spread awareness through songs and dances.

“We were fighting against caste and religious divisions,” Pandian said. “We encouraged people to sit together and share meals. The Arivoli volunteers made it a point to eat in every household, disregarding caste, to demonstrate equality. Do you see now how many women are riding bicycles?”

Fatima, a secondary school teacher, said she never imagined that learning to ride a bicycle would give her so much freedom. “Now I don’t have to depend on anyone. It has completely changed my life,” she said with conviction.

Sarala, an anganwadi teacher, recalled the early days of learning to ride a bicycle.

“There was such an uproar back then. The men reacted with outright hostility. They hurled many insults at us. But the Arivoli workers stood by us. When many women began to learn, those men had no choice but to sit quietly and watch. Eventually, society accepted us,” she said.

I went around several places in Pudukkottai in search of Kannammal, who had led the cycling movement initially. After much effort, I found her — she now works as an assistant at the LIC branch in Pudukkottai.

Kannammal was astonished that I had come all the way from Kerala to meet the woman who had taught the women of Pudukkottai to ride bicycles.

“Oh, back then, things were completely different,” she said. “Girls weren’t allowed to study beyond the fourth or fifth standard. There were no schools nearby; they were far away. Once the girls reached puberty, it became impossible for them to walk such long distances to school, and they dropped out.

“In 1991, when Arivoli Iyakkam launched a literacy drive across the state, lakhs of people came forward to learn. But very few of them were women. That’s when Sheela Rani Chunkath Madam came up with the idea of a bicycle scheme.

“I was the first woman to learn to ride a bicycle. People used to say that if women started cycling, it would be the end of the world — that rains would stop, that it would be a curse! But Sheela Madam stood firm and faced all such criticism with determination.

“She gave me the strength to stand up to everything with confidence. I taught many other women to ride bicycles and helped them gain confidence too. The government gave us strong support. We made it clear to everyone — to the government, that we wanted to learn; to ourselves, that we could learn; and to society, that we deserved to be accepted.”

Those days, whenever a woman needed to get something done from a government office, she was required to prove she could ride a bicycle. If a woman went to collect a paper or document, officials would ask her to show that she could cycle. This, in turn, made it impossible for men to prevent women from learning — and that’s how the project gained social acceptance, Kannammal said.

“The bicycle scheme spread like a social revolution. Bicycle training centres for women, cycling competitions, rallies, demonstrations, lucky dips, prizes — so many programmes were organized. Thousands of women who initially learned cycling only to win a prize eventually made it a part of their everyday lives. For anganwadi teachers, cycling was made mandatory. Today, just as a child learns to walk, girls learn to ride a bicycle as they grow up. Similarly, the Tamil Nadu government now provides free bicycles to all schoolgirls.”

Listening to Kannammal and seeing the women of Pudukkottai, one thing became clear: the very foundation of a woman’s self-confidence is her freedom of movement.

“When women began coming forward to learn cycling, there was an acute shortage of bicycles,” Kannammal said. “Women learned using the men’s bicycles. That actually turned out to be an advantage — since those cycles had a bar in the middle, men would seat children in front and ride long distances to fetch water. Later, women used the same cycles, seating their children on the back carrier, and it made fetching drinking water so much easier.”

Earlier, they used to walk long distances every day to collect water. Once they learned cycling, that burden was reduced. It also became easier to take goods and farm produce to the market. These may seem like ordinary things now, but back then, for women who had spent their lives inside the kitchen, appearing in public on a vehicle was a symbol of rising social status.

“Their circles of friendship expanded. They recognized their own strength. In truth, beyond just economic improvement, learning to cycle gave women self-respect, freedom and fulfillment,” Kannammal said.

When Sainath visited Pudukkottai in 1991, he had witnessed the early stages of the cycling movement. What I saw when I went there was the outcome — women who had stepped out from their homes are now deeply engaged in public life.

The history of cycling in Pudukkottai clearly shows that whether in a village or in a city, when sincere efforts are launched to empower/uplift women, they respond rapidly — and change truly follows.

Kannammal spoke about Women’s Day in 1992: “That year, the Women’s Day in Pudukkottai was like witnessing a historic event. Around 1,500 women tied the Indian tricolour to their bicycle handlebars and rode together in a grand rally through the town. I had never before seen such an expression of confidence.”

Cycling not only changed women’s quality of life but, as Kannammal said, it enabled them to come out of their homes and live alongside men as equals.

What I saw in Pudukkottai is this: when someone in power understands women’s movements and issues and when even a few committed people work sincerely for them, women’s lives can transform completely.

As I left, a song by Jayachandar came to my mind:

“Yes, brother, I have learned to ride a bicycle.

I now move with the wheels of time.”

In a country where so many women still cannot move freely, the women of a Tamil Nadu village learned to balance on two wheels — and through it, found freedom, confidence and progress. It remains a tale that continues to inspire, its revolutionary resplendence as radiant as ever.

Courtesy: The AIDEM