More Indians than ever before now have access to a toilet, but little attention to education and changing attitudes means that at least 522 million Indians still defecate in the open–leaving many millions susceptible to disease and poverty.

Access to sanitation reduces the incidence of diarrhoea–caused by bacterial, viral and parasitic infections, mostly spread by faeces-contaminated water–studies show. Diarrhoea is the leading cause of malnutrition, and is the second leading cause of death in children under five years, as IndiaSpend reported in July 2017.

As of January 2018–with a year and a half left to the Swachh Bharat Mission’s target of eradicating open defecation–60 million (76%) rural households and 4.2 million urban households have a toilet, and 11 states, 1,846 cities and 314,824 villages have declared themselves open-defecation-free (ODF), according to data available on the Swachh Bharat Mission (Clean India Mission) website.

“The challenge, however, will be in ensuring that ODF villages and cities are firstly, truly ODF, but more crucially that they remain so,” as Avani Kapur, fellow at Accountability Initiative, pointed out in this January 2018 article for Mint.

The Centre’s expenditure on information and education–which experts say is the key to solving India’s sanitation problem–continue to remain low.

It is in this backdrop that Finance Minister Arun Jaitley is set to present his government’s last full budget ahead of the general elections in 2019.

Access to sanitation improves child health, leads to more productive adults

Sanitation is crucial for India’s plans to reduce infant mortality. The National Health Policy, released in March 2017, aims to reduce the country’s infant mortality–deaths of children under the age of one–from 41 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2015-16 to 28 in 2019.

“If you live next to neighbours who defecate in the open, there are germs on the ground, lot of the people don’t wear shoes, they get their fingers on it [germs], their moms get their fingers on it and then there are flies on it and they get on the food and the entire environment is where is lot of faeces and there is lot of opportunity to get on germs,” Dean Spears, co-founder of the Research Institute for Compassionate Economics, told IndiaSpend in this August 2017 interview.

This cascading effect of health hazards is corroborated by data: Diarrhoea, as we said, remains the second leading cause of death in children under five years, killing an estimated 321 children every day in 2015, as we reported in July 2017.

Access to sanitation reduces cases of diarrhoea, one of the major causes of malnutrition among children, according to this World Bank study.

As many as 50.2% boys and 44.6% of girls with no access to toilets are stunted, compared to 26% boys and 24% girls who live in homes with toilets, according to this September 2017 study released by the National Institute of Nutrition.

Source: National Institute of Nutrition

Unsafe water, poor hygiene practices and inadequate sanitation are not only the causes of the continued high incidence of diarrhoeal diseases but a significant contributing factor in under-five mortality caused by pneumonia, neonatal disorders and undernutrition, according to this 2016 report by the United Nations Children’s Fund.

Besides, there is also an economic cost to the problem.

“If children are healthy when they are babies then they grow up stronger and taller, they are able to concentrate at school and learn more and they have higher achievement,” Spears told us in the above mentioned interview. “We find that adults are paid more and are more productive if they are born in a better disease environment. Their families get to consume more and they pay more taxes and government gets more revenue.”

“If you can cause a household to stop defecating in the open, just one household, there would be money in the future but it will be an equivalent of increasing the revenue of India by Rs 20,000 per household. That’s just looking at government’s revenue, but then the family gets to eat more, there is more productivity and they will be healthier and they will be more likely to survive,” Spears added.

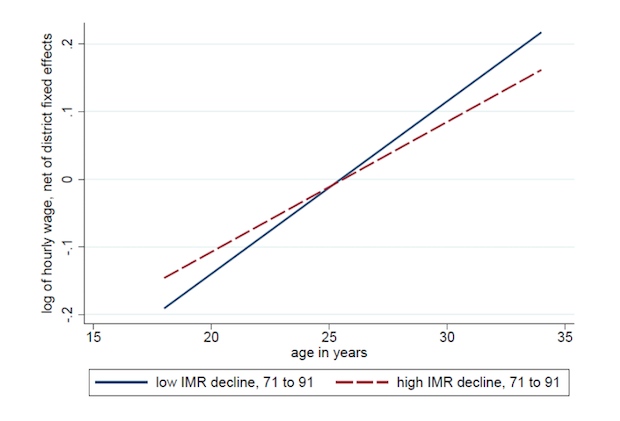

What Doesn’t Kill You Makes You Poorer: Adult Wages And Early-Life Mortality In India

Source: R.I.C.E

Inadequate sanitation–management of human excreta, solid waste, and drainage–costs India Rs 2.4 trillion ($53.8 billion) every year in losses due health, damage to drinking water and tourism costs, according to a January 2011 World Bank study.

Allocation to rural sanitation up 33%, but sub-par spending on education hinders toilet use

In 2017-18, the Centre allocated Rs 13,948 crore for SBM-G–administered by the ministry of drinking water and sanitation. This was a 33% increase over 2016-17 when Rs 10,500 crore was allocated to the programme.

However, expenditure on information, education and communication (IEC)–vital for changing personal attitudes and perspectives–has been below par.

The programme guidelines recommend that 8% of SBM-G and 12% of SBM-U expenditure be earmarked for IEC. In no year has this target been met.

For instance, in 2017-18, only 4% of the allocations to SBM were earmarked for IEC.

Consequently, 22.6% Indians who had a toilet at home but did not use one said it was because of “personal preference”, according to the Swachhta Status report 2016.

“Lot of families with latrines think that if they use them, it will pollute their home and they will never be able to empty them,” Spears told us in the above mentioned interview. “To avoid all this, it is easier is to defecate in the open. It is going to be a hard problem to solve because it is rooted in these old and strongly held issues of social inequality.”

As of January 2018, 11 states and union territories have declared themselves as ODF. However, only six of them have been verified by ministry of drinking water and sanitation.

In rural India, 51% of 604,084 villages have been declared ODF. However, only 64% of these had been verified as of January 15, 2018.

Since October 2014, 60 million households toilets have been built under SBM-G.

Of Rs 13,948 crore ($2.1 billion) allocated to SBM-G in 2017-18, Rs 79 crore ($12.3 million) was for solid- and liquid-waste management. As many as 3.8% rural Indians who chose not to use toilets said broken toilets were the reason they defecated in the open, according to the Swachhta Status report 2016.

The urban challenge: 58% cities still report open defecation, only 23% garbage is treated

As of December 2017, 1,846 (42%) Indian cities declared themselves ODF, of which 1,337 were verified by the ministry of urban development.

As of November 2017, 4.2 million individual household toilets–64% of the 6.6 million targeted–were constructed across Indian cities. Similarly, 92% of the 17,193 targeted community toilets were constructed, data show.

Besides eradicating open defecation and constructing household and community toilets, SBM-U also aims to achieve 100% garbage collection and disposal. As of January 10, 2018, 68% of India’s 82,607 wards–urban administrative zones–had achieved this target.

Solid waste management, however, remains a challenge. As of November 2017, India generates 145,626 tonnes of solid waste every day; only 23% of this is processed.

For SBM-U–administered by the ministry of urban development–the Centre allocated Rs 2,300 crore in 2017-18, the same as 2016-17.

Since 2014-15, the Centre earmarked Rs 7,366 crore for improving solid-waste management systems under SBM-U, of which only 29% has been released to states as of January 10, 2018, according to a report by Accountability Initiative.

This is the concluding part in our series of eight state-of-the-nation reports ahead of Budget 2018. You can read our report on renewable energy here, on agriculture here, on urban development here, on rural jobs here, on healthcare here, on education here and on defence here.

(Salve is an analyst with IndiaSpend.)

Courtesy: India Spend