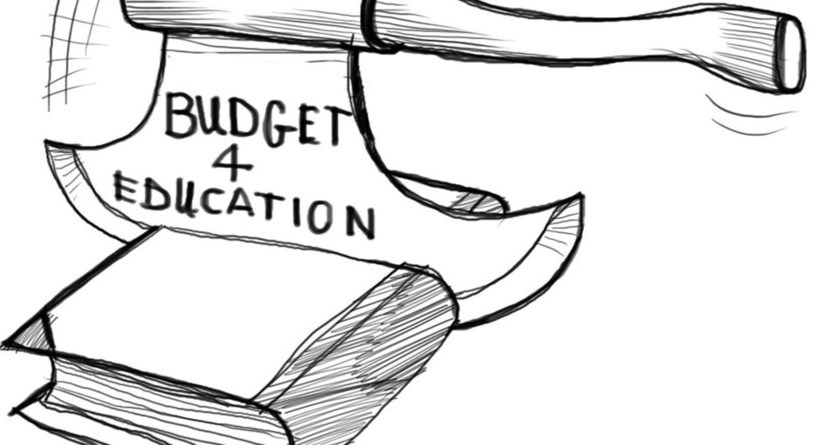

In the Union Budget 2020, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman earmarked Rs. 99,311 crore for the education sector in 2020 – 21 and around Rs. 3,000 crore on skill development. In the 2020 – 21 budget, the major chunk – Rs. 59,845 crore has gone to the school education and literacy department, the fledgling higher education department has received a paltry Rs. 39,466 crore. While Rs. 99,311 crore does look like a whopping statistic, on closer look it reveals only a 5 percent increase from the previous year’s allocation which was Rs. 94,800 crore. Digging deeper, it also shows that the amount dedicated to boost higher education just does not fulfil the requirements of the sector.

Budgetary allocation

This year, in the budget announced by Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman, there was a proposed 3 percent increase for education, a figure that is lesser than inflation which stood at 7.35 percent, reported The Telegraph. The FM also said that steps to allow 100 percent foreign direct investment to ensure high quality education would be taken soon. Sitharaman also announced the establishment of hospitals and medical colleges in every district through the public-private-partnership model.

A sum of Rs 500 crore has been allocated for the Prime Minister’s dream “world-class institutions” project, against Rs 400 crore last year. The scheme aims to provide 10 government institutions with Rs 1,000 crore each over five years.

For higher education, the budget allocated for 2020-21 Rs. 39,466 against Rs. 38,317 in 2019-20. The budget allocated for scholarships fell to Rs. 141 crore in 2020 – 21 from Rs. 356 crore in the current fiscal. This after the University Grants Commission trying to abolish the non-National Eligibility Test (NET) fellowship citing shortage of funds which was rolled back after a student protest. The non-NET fellowship granted every PhD scholar Rs. 8,000 a month and MPhil student Rs. 5,000 a month, a boon for students from poor families. In 2018, out of the total education budget of Rs. 81,868 crore, Rs. 35,010 was allocated for higher education which was 46% percent of the total budget as compared to 39.4 percent of the current budget. In 2017, this number stood at 41 percent and in 2016 it was 39.83 percent.

The 2020 budget also emphasized the need for quality teacher education, but the reduced budgetary outlay for the same from Rs. 870 crores in 2018-19, to Rs. 125 crore in 2019-20 and now to Rs. 110 crore for 2020-21, just goes to suggest that the government has not made this a priority.

Experts speak on why the higher education is still set to suffer

The decision of the government to attract FDI only goes to indicate that government funding towards education would decline in the future. This would lead to higher privatisation and higher fees, a move that all higher education institutes, especially the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) and Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) have been fighting for so long.

Through the proposed PPP model, the shift of the government in financing medical education is also apparent. It has not allocated any budget to establishing new medical colleges and adding seats to government medical colleges in the current budget.

Girish Shahane a writer on politics, history and art expressed his opinion on Livemint saying, “As the Centre curtails provisions, universities have sought to bolster other sources of income. A sharp increase in room rents and mess charges in late October sparked an agitation in Delhi’s JNU which culminated in a ghastly attack on the campus by masked activists on January 5. Opponents of the fee hike pointed out that nearly 40% of students admitted to JNU had a monthly family income below ₹12,000, and would find it difficult, if not impossible, to pay the rates enumerated in the new hostel manual, especially a new monthly service charge of ₹1,700.”

Already the Union budget of 2018-19 scrapped grants for creating new infrastructure within institutions like Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs) and Central Universities. In its place, the Higher Education Financing Agency (Hefa), a joint venture between the human resources ministry and Canara Bank, would provide loans to approved projects, which would be “serviced through internal accruals”. The Centre was to pay the interest on the loans, but the principal amounts were to be paid by the institutions through research and consultancy – revenue amounts no university could generated on its own and had to borrow.

Universities could launch endowment funds to attract donations, but were less likely to garner generous support from philanthropic organizations to fill the huge void left by the government.

Former vice-chancellor of Ambedkar University, Prof. Shyam Menon, told The Telegraph that without subsidised higher education of acceptable quality, the poor and marginalised would have no way to transcend their social and economic obstacles and aspire to claim their legitimate share of India’s economic growth. He said, “They will be the first ones to be affected by any kind of reduction in subsidy. It is so unfair that the state is rolling back its commitment to support public higher education just when the first-generation school graduates from the margins attempt to access it. This is their only chance for any kind of social mobility.” Menon also said that in the past two decades, ignoring the recommendations of the Kothari Commission 1966, the government had sought to shift from liberal to technical and professional streams after being influenced by the Ambani-Birla report of 2000.![]()

The Kothari Commission 1966 and the Niti Aayog had recommended that India should increase its education expenditure to nearly 6 percent of its GDP over the next four years. However, that number currently stands at just a little above 3 percent.

Speaking to The Telegraph, Professor Amitabh Kundu, a distinguished fellow at the government think tank Research and Information System, also disapproved of the recent practice of the government to ask institutions to raise funds internally to manage their expenditure. “Education should be a part of the superstructure which should guide the creation of the economic and social structure rather than being subservient to the latter. The institutions thereby will fail to build an environment and culture of independent thinking on larger issues of societal change and inclusive development,” he said.

From the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) to JNU to the students of MTech, higher education institutes have been continuously protesting against the fee hikes imposed on the students. The government’s budget cuts have forced the institutions to ramp up their fees, thus forcing the ones for socio-economically weak backgrounds to be left out of the fold of education.