The Padman Revolution

Image Courtesy:New Indian Express

“Period” was a word that spelt blasphemy in Indian families up until recent times. Or, does it still exist for girls and women, who are trained to refer to periods as “that time of the month,” or, “chums,” or, as Akshay Kumar’s Padman shows, “five day cricket match?” The taboo around the subject, however, does not prevent boys on the streets from making fun of women when they “sit outside,” or, when a girl becomes “siyani”—which occasions a grand celebration of the girl’s first period. Akshay Kumar’s film focusses on this, and how the girl herself thrives on being the centre of attention with all the chutzpah and the jewellery and the music and song, without really understanding what the future holds for her.

But, wait. Arunachalam Muruganantham, on whom the movie is based, has been the central subject of two, very good documentaries in the past. Two noted documentaries have been made by two different people over two years. One is The Menstrual Man (2013), made by the Singapore-based Amit Vrimani, and the other one is The Pad Piper, by Akanksha Sood Singh, which bagged the award for the Best Science and Technology Film at the 61st National Film Awards. The award was bestowed “for its portrayal of a sensitive man with a profound belief in appropriate technology, who came up with a simple piece of engineering – an affordable sanitary napkin that has had an extraordinary impact on the health of millions of poor women.”

Sood, who made The Pad Piper, says, “A man trying to break into a market shrouded in mystery and myth surrounding women was intriguing. The reality was shocking. I always thought women use cloth as an alternative. But sand, newspapers, cow dung? And those who don’t wear under garments? My mother, like most mothers, advised me to not go to the temple or touch pickle during my periods. When I would ask her why, she did not have convincing answers. After a point, I stopped believing in these myths. Then, I wondered—what about women who are considered “dirty” when they bleed and are thrown out of the village for 3– 5 days, abandoned in a hut with little food, no company, and no bath? Do they know they have a choice? They did not. Then Muruganantham arrived and changed their lives.”

Vrimani’s film had sold-out screenings at both the Hot Docs Canadian International Documentary Festival (Toronto) and the International Documentary Filmfestival Amsterdam, arguably the two most influential documentary festivals in the world. “…We were among the audience favourites at both,” says Virmani, adding, “We got a lot of social media buzz because people [were] inspired by the story and [wanted] to share it with their friends. Rosie O’Donnell watched the film and tweeted about it, encouraging her fans not to miss the film. All very humbling but, more importantly, also a confirmation that the film’s themes of hope, triumph, and female empowerment resonate with people everywhere.”

A third film, a docu-fiction, Roll Number 17, was entered at the 23rd Kolkata International Film Festival last year, in the documentary and short film section. Directed by Dhananjoy Mandal, the film was a celluloid adaptation of the real-life tragedy of Ananya, a girl in VIII standard of a co-educational school in the Sundarbans, who fell victim to a fatal disease from infection due to the lack of access to toilets and hygiene. She stopped attending school after she fell ill, never to come back again. The Principal of the school said that the drop-out rate and absenteeism among girls in the school was very high, mainly because of their periods and the inaccessibility of hygienic ways of dealing with it.

Her grief-stricken friends were doubtful about whether they would ever be able attend school, especially during their periods. This is when the concerned headmaster, with his single-minded commitment and dedication, decided to solve the problem. He approached several NGOs and government departments for funding, and succeeded in building two hygienic toilets, one for boys and one for girls, in the school. Worried about unhygienic practices by girls during their periods, he gathered funding to set up a sanitary napkin-vending machine within the school. Girls were required to use the vending machine to get their napkin. This created a new culture, a new social practice, and a new way of looking at girls. But this film was rejected by the selection committee and is waiting to see the light of day. However, this is the only film that shows the breaking of this social taboo without referring to the work done by Arunachalam Muruganantham and is based on actual events that happened in the relatively remote area of the Sundarbans.

The one thing that Akshay Kumar has done through his entirely mainstream film, with songs and romance and a touch of romance beyond marriage, is that it has truly drawn a lot of attention—of the good kind among the general population— to the issue at hand. Padman is a masala film from beginning to end, but it has a purpose to serve and, set as it is in the middle of a small town in Madhya Pradesh, it reveals the crudeness of the local people (among both men and women) towards life, in general, and towards this “woman’s problem,” in particular. His long lecture, the climax of the film, at the United Nations is both melodramatic in the extreme and, also, derogatory of Lakshmikant’s own invention because the similarities he draws between (and among) Superman, Batman, and Spiderman on the one hand, and that of the Padman on the other, slights and sidetracks the entire contribution of the innovative scientist-cum-social activist at one go. The comic characters like Superman are fiction and are based on pure fantasy, while Arunachalam is a man who actually exists and is still striving to spread the distribution of his machine to women across the country.

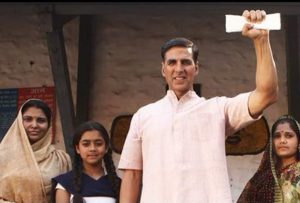

Pricking the conscience are the wrong ways in which the film’s promos came across which, at times, reduces the agenda of the film to a poor joke. “The Padman Challenge,” as it was dubbed, according to this writer, did not achieve even half of what the film achieved through specially organised screenings in schools with the aim of raising social awareness and education, both for the students and for the teaching faculty. The Padman Challenge was created as a social media campaign where celebrities, mainly from the tinsel world of Bollywood, were invited to take the challenge which required them to pose with a sanitary napkin in their hand and post the picture on their social media sites. So, stars like Aamir Khan, Deepika Padukone, Katrina Kaif, Tiger Shroff, and Akshay Kumar himself, posed with sanitary napkins in their hands. They are smiling into the camera, as if they are posing for an ad campaign and not for a socially productive act. Their flippant smiles belie the seriousness of the pad, and its importance for rural women’s health, for their “selfies” or whatever. Why?

Looking at the spread of the movement, one feels that this challenge was not really necessary. Chanakya Grover in his enlightening piece, Just the Beginning of the Challenge (The Spectrum, Tribune, Sunday, February 18, 2018) writes, “It would be prudent for us to realise that it is but a small step towards a revolution; and certainly not a Pan-Indian one because the women who need our support, who need sanitary pads or menstruation cups, don’t know about them or can’t afford them. They are not online, not logged on to Twitter, Instagram, are unaware of the fancy Snapchat stories and don’t read newspapers.” He goes on to add, “They would certainly benefit more from a one-to-one talk about the issue and a free sample of pads and menstrual cups, than with our online posturing. Well-researched, result-oriented campaigns educating women and men alike on menstrual hygiene would help more than the synthetic online campaigns.”

However, the film and its promotional campaign across the country brought to light others who are engaged in similar campaigns. Shobhon Mukherjee lives in Bansdroni, a Kolkata suburb. He was pleasantly surprised with a phone call one winter morning when the caller informed him that Akshay Kumar wished to talk to him. The actor spoke to him for a few minutes and told him to carry on the movement he had pioneered himself. What movement? Shobhon, who, after the release of Padman has been dubbed the “Padman of Kolkata,” had begun a unique movement in the city. What movement? “It is a very small attempt to alleviate girls of a regular problem but it is also a very important one,” he says.

He visits public toilets across the city and places sanitary napkins in boxes that he makes out of empty ice-cream cartons. The young man—who is doing his post-graduation in Geography, pursuing a diploma course from the Indian Institute of Health Training, and running a magazine, all by by himself—began this crusade in October last year. “It was triggered by a small incident. A friend of mine, whom I was supposed to meet, called me up and said she that could not make it because she had just gotten her periods and was not carrying any sanitary napkins with her. That set me thinking—hundreds of girls and women, students, housewives, working women, mothers, sisters, they all face the same problem every other day. They do not always have napkins, or, even if they do, there might not be a public toilet nearby.” He calls this Project Bandhan; bandhan means “bonding.” He chose this name, firstly, because it was a way of “bonding” with his “sisters,” (he began this movement just a day before Brother’s Day), and, secondly, because the “bonding” stands for the bonds that exist between a mother and her children. Till date, Shobhon has placed these boxes in the ladies’ section of 15 public toilets across Bansdroni, where he lives, and in Ganguli Bagan, Garia, Rath Tala, and Kalighat, after obtaining clearance from the respective councillors, who were quite cooperative.

Like Lakshmikant Chauhan, Shobhon has also been at the receiving end of brickbats, negative reactions, acidic barbs, and potshots, especially from men. “A social media page, sarcastically, asked me why I was doing all this even after the film’s release. This is not true at all. I am determined to go on doing what I had decided to do. I saw the film but I was already doing it in a different way with a different agenda. What the film has done is that it has brought attention to me and to my work and that has been a great help. I do not recall anyone calling me to commend me for this work,” he adds. A local pharmacist was puzzled when he noticed that Shobhon came to his shop to buy sanitary napkins every week. But, when Shobhon explained the reason, he accepted and supported the movement. Shobhon is not very comfortable with the nickname “The Padman of Kolkata.”

His friends, family members, the local councillors, and some strangers have not only appreciated his work but have also come forward to help in their own way. His parents—his father works in a bank and his mother is a housewife—have encouraged him every bit of the way. He began with his personal savings, but, as the news spread, money began to pour in. The first help came from an unknown person in Manipal. Now, money keeps pouring into his bank account and his PayTM account, from students, IT people, and others, ranging from Rs 50 to Rs 100. “But, this positive change has come only after Padman released,” he admits.

Shobhon’s activism is only one side of the awareness campaign. Padman, the film itself, is helping in a large way in dispelling myths, breaking taboos, and spreading the message of the importance of hygiene among growing girls through special screenings across cities. A special screening of the film was held for 400 girls studying in ten schools within Balurghat city, and ten neighbouring villages, by the district magistrate Sharad Kumar Dwivedi. Many of the girls came out of the screening and admitted that they did not use sanitary pads because they could not afford them. This open admission, of not being able to use pads, is itself an example of girls talking openly about periods and its associated problems. Twelve members of a local women’s NGO, Alo, had also been invited to this screening. They informed the girls that they were soon planning to release cheap sanitary napkins in the market. The Alo Female Co-operative Credit Society, together with multiple Self Help Groups, has begun its mission to produce sanitary napkins for women residing in rural areas. Sources at the organisation claim that 20 women have already been trained, and have started making the pads. A packet containing ten pieces of these pads will be sold for Rs 27.

After the show was over, the girls came out of Satyajit theatre to click selfies in front of the poster of Padman. Nandita Das, Headmistress of Ayodhya K.D. Vidyaniketan, watched the film along with her students. “This is a very timely film that, I hope, will raise awareness among the girls. I always keep a stock of sanitary pads in my office to fulfill the needs of the girls who need them suddenly. But it is still very expensive for girls in small towns and villages, and it is necessary for the state government to supply cheap sanitary pads to schools.” Krishna Karmakar, assistant teacher at Kabitirtha Vidya Niketan, said that 60% of the girls in her school did not use sanitary napkins. She added that, along with the girls, their mothers should also watch special screenings of Padman so that they become aware of the dangers of unhygienic menstrual practices.

The girls agreed in that they could not afford to buy sanitary napkins and pads. They belong to a cross-section of schools where Padman was being screened specially for them. There are other issues too, for them not using pads—they were shy to ask their families for money to buy pads, or, they felt uncomfortable visiting shops to buy pads, even if some of them could afford them. After watching Padman, however, they are convinced that they will be able to cross these social and family hurdles, and gather the courage to come out of their shells and talk about periods openly.

The two questions that keep nagging us, however, is, (a) why do women always need a man to deal with their problems? Does this not reaffirm the role of patriarchy in society and in the economy? (b) Why must a film like Padman, which is very serious and socially relevant, fall back on a production house that calls itself Mrs. Funnybones Movies? This is not funny, really.

First published on Indian Cultural Forum