There seems to a consensus within Islamic theology that homosexuality is not permissible, rather it constitutes a grave sin in the eyes of God. Certain Quranic verses point to this practice and its violent disapproval by God.

As a matter of fact, Judaism, Christianity and Islam, all seem to be decidedly against it. The Leviticus declares it abominable for a man to lie with another man as with a woman, and the command is that, irrespective of whether the act is consensual or not, both partners are to be executed. For Jews, Christians and Muslims, the story of Sodom is central to their attitude of condemning homosexual acts. The Prophet Lot of the Bible becomes Prophet Lut in Quran. The Arabic term for homosexual anal intercourse, Liwat, comes from his name as the English term sodomy is derived from Sodom, the town of Lot and his people.

The Quran tells us that Lot offers his daughters to the crowd lusting after his male guests but fails to convince them. The verse

‘Indeed you approach men with desire/lust, instead of women; rather, you are a transgressing people’ is cited as proof that God condemns same sex unions and that the only natural desire that men should have is towards women.

At other places, the Quran affirms the principle of heterosexual unions as the normativity that is expected of Muslims. Certainly, no punishment is specified in the Quran, but it cannot be read to mean that the text is permissive of same sex unions.

This understandably creates anxiety in the queer Muslim community as they do not find any basis to reconcile their sexuality with their faith. They either have to ‘choose’ their sexual identity or their religious faith. Many, however, argue that their sexual identity is not a matter of choice, it is who they are and since God has made them what they are, His religion should not discriminate against them. For them and many others, reading the Quran in a way which empathises with same sex unions becomes imperative. Gay Muslim activists have argued that the message in the story of Lut is essentially about inhospitality and rape of male visitors. And therefore, should not be interpreted to condemn same sex love. Relying on exegetical literature, they have argued that actions of Lot’s people included ‘ambushing travellers, apprehending their goods and killing them’ and that they were eventually punished for such crimes rather than for having same sex desires.

They have also delved into Hadith literature which have unequivocally called for the killing of those engaging in same sex behaviour. The Prophet of Islam is supposed to have declared that both the active and passive partner should be subject to the same penalty as for zina (illicit heterosexual act), namely execution by stoning. Abu Dawud records a report from Abdullah ibn Abbas: The Prophet (PBUH) said, ‘If you find anyone doing as Lot’s people did, kill the one who does it, and the one to whom it is done’. Clearly there is no mention here of either consent or its absence, the very act itself is to be condemned and punished.

But then it is also true that Hadiths have major issues regarding their authenticity. Traditional Muslim scholars have themselves pointed it out and have debunked Hadiths either on the basis of weak chain of transmission or on the doubtful character of the transmitter. Academics like Scot Kugle (Siraj al Haqq) have demonstrated how many of such Hadiths are very weak and therefore cannot be considered authentic and relied upon. But Kugle even goes further. His revisionism argues that the appreciation of diversity is one of the key messages of Quran. It follows from this that diversity of sexual experiences should be not be condemned but welcomed by the Muslim world since it is part of God’s plan. However, this kind of hermeneutic jugglery fails to convince many who think that if indeed sexual diversity was part of God’s plan, then, why is the practice condemned by Him? They argue it is clear from the Quran that linguistic and ethnic diversity is desired by God, but not sexual diversity.

Some have tried to get over this problem by pointing out that historically, Muslim societies have been very tolerant towards same sex relationships. This is certainly true. From poetry to politics, same sex relationships were not just tolerated but even considered normal for male adults. It was expected that adult males will be attracted to both boys and women. Certainly this was not a democratic relationship between two consenting adults, with young boys having no say in this act whatsoever. Nevertheless, there was no shame attached to having sex with boys. Form Delhi to al-Andalus, the practice was certainly widespread. In fact, the Ottomans, for all practical purposes, decriminalised homosexuality way back in 1858 itself. However, this does not mean that Islamic heterosexual normativity changed in the wake of this practice. The scriptural position continued to remain the same and same sex unions were not looked upon favourably. It was as if the Islamic scripture and the Muslim practice were at a dissonance.

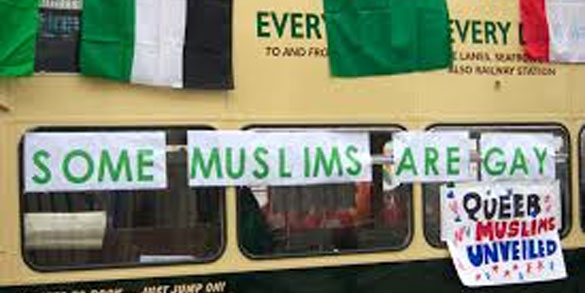

This then constitutes a problem at two levels. The first is that those Muslims who are not heterosexual find it extremely suffocating to live within this religious tradition. Under the pressure of society and family, they either try to ‘reform’ themselves or are left with no choice but to leave Islam altogether. Both choices are extremely painful as it amounts to negating part of their selves. At another level, this inhibits a broader solidarity between Muslims and LGBTQ groups, as these groups would not align with a religion which has a very negative attitude towards them.

Some Muslims have tried to get round the issue by adopting something like don’t say don’t tell policy. Thus they are not concerned with what two individuals privately indulging in homosexual acts till the time they remain discreet about it. This approach, adopted by Zakir Naik and others, misses the very essence of contemporary gay identity. The struggle of the gay movement today everywhere is to be recognised as a legitimate identity within the public sphere. Not talking about it openly therefore defeats the very purpose of their struggle.

Some Muslims have also argued that while they can enter in alliance with LGBTQ, they can never accept that these sexual practices are right as it goes against their religion. This position might lessen the guilt of heterosexual Muslims, but it hardly helps the LGBTQ community, Muslim or otherwise. If Muslim recognition of homosexual identities does not come with a positive affirmation, then it is no less violent than non-recognition itself.

It must be recognised that Islam does have a problem with modern homosexuality. We also must recognise that the problem is fundamentally at the level of the scripture which inhibits believing Muslims to affirm the rights and practices of LGBTQ. Therefore, a solution must be found at the scriptural level itself. So far, such hermeneutical engagement with Quran has not been entirely convincing. Certainly, Islam is not unique and similar condemnation of homosexuality can be found within Judaism and Christianity. But nearly two centuries of Biblical criticism have brought the heavens down to the earth, the text hollowed out of its sacredness. Newer, more contemporary interpretations arose which made it easier for Judaism and Christianity to accommodate a whole host of people and ideas who were earlier deemed unworthy. A similar exercise needs to happen within the Muslim world. The sooner this happens the better it will be, for Islam, Muslims and the wider world.

Arshad Alam is a columnist with NewAgeIslam.com

Courtesy: NewAgeIslam.com