In this 2005 photo, Rattan Singh Kalsi shows a photograph of his daughter, Indira, at a meeting with families of the victims of the 1985 Air India bombing.

Rattan Singh Kalsi kept photos of all his grown children in his room at the seniors’ home, but one of them towered over the rest.

The photo anchored a kind of shrine to his daughter, Indira, who had died more than 30 years earlier, just as she was entering adulthood.

Indira had grown up in Canada and Rattan had bought her a plane ticket so she could see India, the country their family had come from, and spend time with the relatives she might not get to see once the responsibilities of work and adult life set in.

Naturally, Rattan, who had been middle-aged at the time of Indira’s death, was heartbroken when she was killed in the bombing of the plane. He never recovered. He was not responsible for what had happened, but he blamed himself and lived in quiet anguish for the rest of his life.

Not long before he died, he shared his story. I was there to record it, and it was unbearably sad for both of us.

Rattan had left behind a request to scatter his and his wife’s ashes (she had died some years earlier) over the same patch of ocean where the remains of the plane carrying their daughter had splashed down.

Bomb planted in Canada

All 329 people on board Air India Flight 182 on June 23, 1985, were killed, including 280 citizens or permanent residents of Canada.

They were lost to a bomb that exploded while their plane was in Irish airspace, en route from Canada to India. The bomb had been planted in Canada in an act of terror planned by extremists allegedly advocating for a separate Sikh state in the Punjab.

It was Canada’s worst mass murder, yet it is barely remembered in this country.

Today, Canadians commonly regard the bombing as an Indian tragedy, or at most an Indo-Canadian tragedy. They typically dwell on the terrorism, but rarely on the grief and hardship of fathers, mothers, wives, husbands, children, friends and neighbours left behind.

Why hasn’t this tragedy claimed a prominent place in Canadian history and public memory? Some now call it Canada’s 9/11, but until the attack in New York City some 16 years later, they didn’t call it much at all.

The Canadian families of the dead wonder year after year why no one but them seems to care, or why their grief is seen as less worthy than that of others who are more openly taken into the nation’s heart.

Yes, there was a long criminal trial, a public inquiry and an apology from the federal government for failing to prevent the bombing and for the mistreatment of the families thereafter.

The bombing was belatedly declared “a Canadian tragedy,” so Air India is part of the official record, but it does not appear to be part of the Canadian family album.

‘Broad indifference’

I have no personal connection to the tragedy, but our country’s broad indifference to it came to me as a surprise. A course I was teaching at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont., 25 years or more after the bombing, called for a section on Air India Flight 182, but when I went to look up the scholarly research, I was astonished by how little there was.

The absence of research was consistent with the broader and more troubling fact that the bombing has never resonated as deeply with Canadians as the scale of the tragedy would suggest.

An Indo-Canadian woman shows her two-year-old grandson where the name of her husband and his grandfather, Daljit Singh Grewal, is located on a monument during a memorial marking the 25th anniversary of the Air India bombing in Vancouver, B.C., in June 2010. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck

The mismatch between the tragedy itself and its significance in the public memory may have many explanations, including racism.

It could be that the bombing is regarded as an Indian issue, since it was apparently motivated by political conflicts rooted there, or as an Irish event, since the plane that had taken off in Canada exploded in Irish airspace. It may be that since most of the Canadian victims were of Indian ancestry, that their fellow Canadians discounted them as outsiders or minorities.

Whatever the reason, a great wound had been left to the families to tend to on their own, and history had closed it over, leaving barely a scar for the public to see. The wound represented not only the grief of losing one’s loved one, but the heartache of not being recognized as Canadians, and the loss not being viewed by the Canadian government and fellow citizens as a loss worthy of public mourning.

Since then, I have made it a personal and academic mission to haul this tragic event into the Canadian living room for a broader discussion, partly for the sake of the memory of those who died, and partly for the sake of those who have had to carry on without them.

Memorializing Air India

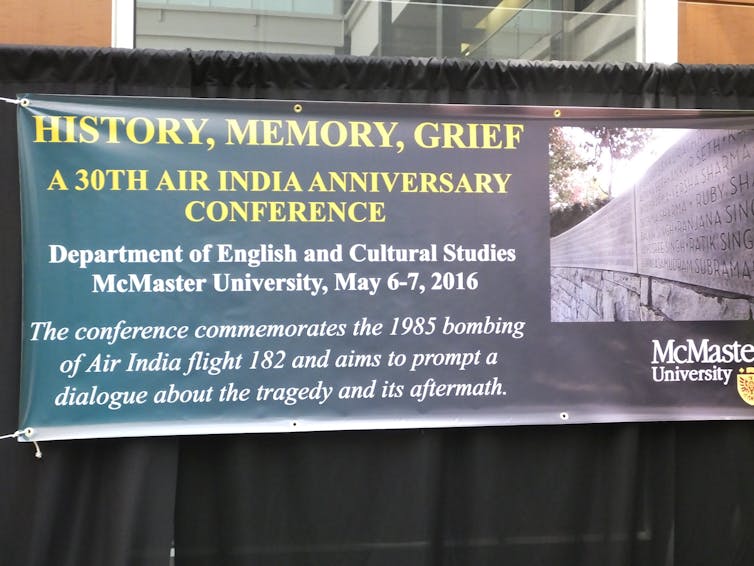

In 2016, toward the end of the 30th anniversary of the tragedy, my colleagues and I organized a two-day conference at McMaster featuring family members, scholars and artists in the hope of bringing the bombing closer to its rightful place in the Canadian consciousness.

(Khursheed Ahmed)

Last year, we published an anthology, Remembering Air India: The Art of Public Mourning that creates a different sort of public record of the bombing than official responses.

In the course of my research, I have had the difficult honour of interviewing dozens of relatives of those who perished on Air India Flight 182. They have taken me inside their pain, and I find their grief substantial, complex and palpable even after three decades.

My work has led me to understand what our country lost in the bombing, and also what we have lost by failing to include the tragedy and its living victims in our collective memory.

At the annual commemoration of the bombing in Toronto every year, Air India families come up to me and ask who I lost. To me, it’s distressing that they have come to expect that only other family members would care enough to come to a memorial service.

Slowly, I am assembling an Air India Flight 182 archive, the first of its kind, featuring families’ scrapbooks, poems, dance, kids’ paintings and recordings and transcripts of interviews with family members, to be housed at the McMaster University library and made available online for users around the world.

My hope is that it will preserve the memory of those who passed away, document the pain of their families and create resources for research that may finally connect this “Canadian tragedy” to Canada itself.

It’s high time.

This article was first published on THECONVERSATION.