“I am not hurt at this moment. I am not sad. I am just empty.”

— Rohith Vemula

It has been ten years since Rohith Vemula’s institutional murder.[1] That emptiness is not his alone. It is the lingering feeling many from marginalised communities carry with them when they enter India’s so-called “elite” institutions –- IITs, IIMs, NITs, and Central Universities.

A 2022 survey in the Quint conducted at IIT Bombay following the Institutional Murder of Darshan Solanki found that one in every three SC/ST students had been asked about their caste identity.

Faculty spaces in these institutions reflect a similar imbalance. Despite constitutionally mandated reservations for SC, ST, and OBC communities, faculty positions continue to be dominated by those from the general category, as reported by The Hindu.

Under representation in these institutions

Under-representation is not incidental; it is structural. In at least two IITs and three IIMs, nearly 90% of faculty positions are held by individuals from the general category. In six IITs and four IIMs, the figure ranges between 80–90%, according to a report by The Wire, based on an RTI filed by Gowd Kiran Kumar, National President of the All India OBC Students Organisation.

The culture of exclusion within India’s elite institutions is not declining. It has been firmly entrenched.

| Sr no. | Indian Institute of management | SC/ ST FACULTY |

| 1. | IIM Bangalore | 1 |

| 2 | IIM Ahmedabad | 0 |

| 3 | IIM Calcutta | 0 |

| 4 | IIM Lucknow | 1 |

| 5 | IIM Indore | 0 |

Source: MHRD Data and a report in Quint, November 28, 2019

Faculty recruitment across IIMs has witnessed a significant decline between 2019 and 2026.

OBC, SC, ST – FACULTY IN IIM’s

| NAME | GENERAL | OBC | SC | ST |

| IIM Ahmedabad | 104 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| IIM Bangalore | 104 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| IIM Calcutta | 86 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| IIM Kozikode | 22 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| IIM Indore | 104 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| IIM Lucknow | 84 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| IIM Shillong | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

This was first put out on social media. Verifying this we found that, according to a report in The Print on “The Parliamentary Standing Committee on Education, Women, Children, Youth and Sports titled “2025–26 Demands for Grants of the Department of Higher Education” as of January 31, 2025, 28.56 percent of the total sanctioned teaching faculty positions (18,940) remained vacant across IITs, National Institutes of Technology (NITs), Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs), Indian Institutes of Science Education and Research (IISERs), Central Universities, and other higher education institutions.

The data further reveals that 17.97 percent of the 11,298 Assistant Professor positions (entry-level posts) are vacant, 38.28 percent of the 5,102 Associate Professor positions (mid-level posts) remain unfilled, and an alarming 56.18 percent of the 2,540 Professor positions are currently unoccupied.

The question then is stark: Why are SC, ST, and OBC positions left unfilled even when institutions have vacancies and eligible candidates are available?

When questioned about their recruitment processes, many institutions claim to follow a “flexi” system. When asked why reservation policies are not implemented, some have anonymously stated that hiring is done purely on “merit”. This raises a troubling question, does “merit” imply that candidates from marginalised communities are deemed intellectually unfit to teach in elite institutions? It is also frequently argued that an “adequate talent pool” is unavailable.

The experience of Subrahmanyam Sadrela illustrates the deeper structural problem. After completing his M.Tech and PhD from IIT Kanpur, Sadrela joined the institute as an Associate Professor in the Aerospace Engineering Department in January 2018. Soon after his appointment, colleagues reportedly remarked that his selection was “wrong”, that he did not deserve to be a faculty member, that his English was inadequate, and that he was mentally unfit. In April 2019 nearly a year after he raised allegations of caste-based discrimination on campus, he was accused of plagiarism in his thesis and threatened with the revocation of his PhD degree, as per a report in the Times of India. A detailed investigation by the Directorate of Civil Rights Enforcement (DCRE) and reported by the Mooknayak said that the corroborated allegations of caste based discrimination inside IIM – B made by an associate professor Dr Gopal Das were vaild.

A significant portion of the 2025 data is not available online. Most publicly accessible information is from 2023–24, with limited material from early to mid-2025. This absence itself is telling, particularly as the pace of erosion of transparency –by institutions under the union government–appeared to accelerate in 2025, as per a report in the Wire.

RTI data from 2024 revealed that no SC, ST, or OBC faculty members were recruited in 2023 at IIT Bombay. Further, 16 departments at IIT-B did not admit a single student belonging to the ST community in the 2023–24 academic year. Shockingly, in five departments at IIT-B, no ST student had been admitted in the last nine years. This data was shared by the Ambedkar Periyar Phule Study Circle (APPSC), a student group at IIT Bombay, based on an RTI response received on February 6, 2025. In a post shared on X (formerly Twitter) on 9 April, the group alleged that IIT Bombay “Is violating reservation norms despite the MMR (Mission Mode Recruitment) announcement.”

Notably, no information was put out by the Circle regarding 2025 data on PhD enrolments or faculty recruitment. The Circle, which had consistently been active in raising questions of injustice, appeared to fall silent on these figures. Speculations can be made that the voice of the student group was curbed by the institute. Established in 2017, the Circle had positioned its X account as a strong voice responding to issues affecting students within and beyond IIT-B.

The death of Darshan Solanki, a Dalit student at IIT-B, further intensified concerns. His father claimed that caste-based harassment led to his son’s suicide. However, the committee constituted by the institute concluded that the suicide was linked to poor academic performance, stating that none of Darshan’s close associates had reported instances of caste-based harassment. It must be noted that the committee did not include a single external member; it comprised only IIT staff. The inquiry was entirely internal. To many, it appeared a complete white wash.

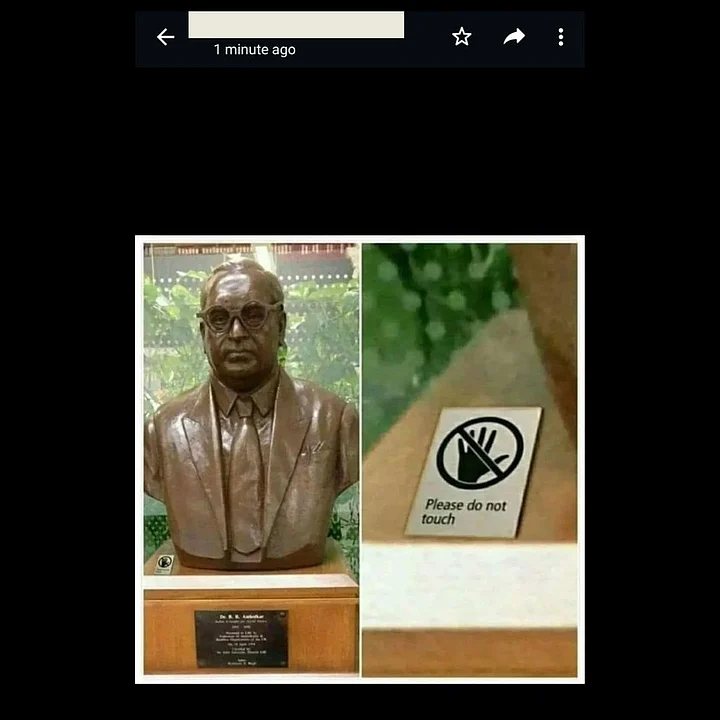

Similar patterns of hostility have surfaced in other premier institutions. Students at the Indian Institute of Mass Communication (IIMC), Delhi, reported that casteist messages such as “SC/ST leave the campus” and “Jai Parshuram” were circulated by fellow students on unofficial WhatsApp groups. Memes targeting Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar were also shared.

When anonymous complaints were submitted, the institute’s director and faculty reportedly responded that since the complaint had been made anonymously, it could not be entertained. This was conveyed by a senior official on the condition of anonymity.

If students are made to feel this unwelcomed within these institutions, why would they not drop out? Why would faculty members not resign?

The dropout rates of SC, ST, and OBC students in these elite institutions are often attributed to financial difficulties or “excessive academic pressure.” Yet, the lived experiences of students suggest a far more troubling reality. Following Darshan Solanki’s death, a survey was conducted at IIT Bombay. Students were asked a series of questions about campus climate and discrimination. One such question, along with several responses, is reproduced here. These responses reveal the brutal reality of a systemic failure—one that institutions attempt to downplay or conceal, even when exposed by the deaths of students like Darshan.

1. What Has The Survey Revealed?

- On being asked if anyone has hurled “caste/tribal slurs or abuses or discriminated against you on campus,” 83.5 percent students said ‘No’.

- While 16.5 percent students said that they had, in fact, witnessed such instances, 70.4 percent students said that they had not witnessed anyone else being discriminated against on campus

- Nearly 25 percent, or one in every four students, said that the fear of disclosing their identity has stopped them from joining an SC/ST forum or collective.

- As many as 15.5 percent of students said that they have faced mental health issues arising from caste-based discrimination.

- Nearly 37 percent of students said that they were asked their Joint Entrance Exam (JEE)/ Graduate Aptitude Test in Engineering (GATE)/ Joint Admission Test for Masters(JAM) /Undergraduate Common Entrance Examination for Design (U)CEED rank by fellow students on campus in a bid to find out their (caste) identity.

- 26 percent of students were asked their surnames with the intention of knowing their caste.

- 6 percent, or one in every five students, said that they feared backlash from the faculty if they talked back against caste discrimination.

- 2 percent, or one in every three students, said that they feel SC/ST Cell needs to do more to address casteism on campus.

- Nearly 25 percent of the 388 students, that is one in every four students, did not attend an English-medium school in class 10.

- Nearly 22 percent of students are first-generation graduates from their family.

- Nearly 36 percent of students foretell that open category students perceive their academic ability as ‘average’. This is in contrast to 51 percent SC/ST students perceiving the academic ability of open category students as ‘very good’. (Source: the Quint)

There is a powerful story from the Solomon Islands that when people wish to uproot a tree, they gather around it and hurl abuses at it until the tree withers and dies. Whether or not this myth holds true for plants, its metaphor is painfully relevant in the context of India’s elite institutions.

An unwelcoming, hostile environment does not merely push students to drop out; it drives faculty members to resign as well.

Vipin V. Veetil resigned from IIT Madras in July, 2021. He had joined in 2019 as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences (HSS) in August the previous year. In his resignation email to the institute’s authorities, Veetil stated that his sole reason for quitting was caste-based discrimination allegedly faced from senior Brahmin faculty members within the department. However, the committee constituted by IIT Madras concluded that there was “no evidence of decisions being biased due to caste discrimination,” reasoning that most faculty members had “hardly interacted” with Dr. Veetil.

This was not the first instance. In January 2022, Veetil had also resigned after rejoining the institute in August 2020.

In another case, K. Ilanchezhian, a senior assistant director at the institute, filed a complaint alleging that his office space had been shifted to a students’ hostel, while his original office was allotted to an ‘upper’ caste research assistant.

Similarly, the Director of the National Institute of Fashion Technology (NIFT), Chennai, was booked at the Taramani police station under the SC/ST Act following allegations of caste discrimination against a colleague.

In 2024, an FIR was registered under various provisions of the SC/ST Act and the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita by the Bengaluru Police in a case alleging caste-based atrocities and systemic discrimination at IIM Bangalore. Eight individuals were named, including the institute’s Director and seven professors. The Directorate of Civil Rights Enforcement (DCRE), in its investigation findings dated December 20, 2024, confirmed systemic caste-based harassment faced by Associate Professor Gopal Das, a globally acclaimed Dalit scholar at IIM Bangalore, as per a report in the Mooknayak.

These cases represent only the tip of the iceberg.

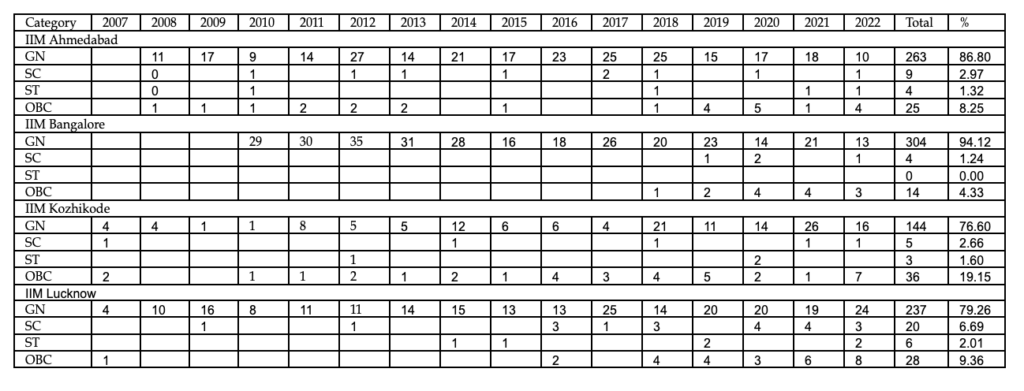

Data on PhD enrolments in these institutions reveals that only a small number of students from SC, ST, and OBC communities have been able to secure admission into these prestigious doctoral programmes

Source: Table showing the 2022 PhD admission data of 13 IIMs obtained by RTI filed by APPSC IIT Bombay, The Wire

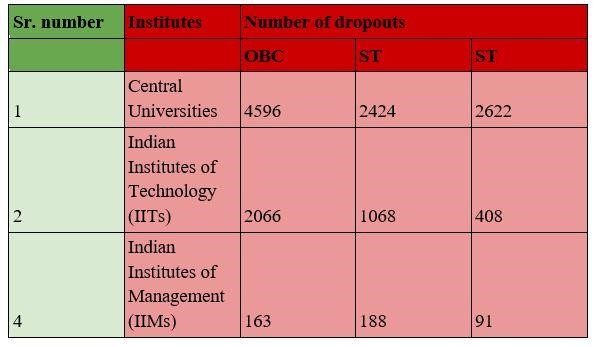

Scholarships for SC, ST, and OBC students are delayed and the students often get the amount after the end of their semesters. It has become an annual tradition for students to receive their scholarships after the end of their academic semester as reported in The Hindu. Minister Subhas Sarkar in this winter session of the Lok Sabha presented statistics that reveal the harrowing figures about dropouts by marginalised students studying in central universities, Indian Institutes of Technology, and Indian Institutes of Management.

In response to a question raised by BSP Member of Parliament (MP), Ritesh Pandey in 2023, the government disclosed that over the preceding five years, a staggering 13,626 SC, ST, and OBC students had discontinued their education.

The data further revealed that in Central Universities alone, 4,596 OBC students, 2,424 SC students, and 2,622 ST students had dropped out during this period. In the IITs, 2,066 OBC students, 1,068 SC students, and 408 ST students discontinued their studies. Similarly, in the IIMs, 163 OBC, 188 SC, and 91 ST students dropped out, reported SabrangIndia.

As stated before, no data for 2025 is accessible as of now, online.

Background

The Department of Personnel and Training (DoPT), the nodal central government agency on matters relating to reservation, issued an order in 1975 exempting certain scientific and technical posts from the reservation policy.

Siddharth Joshi, an IIM Bangalore doctoral alumnus and researcher who co-authored a paper with IIMB Professor Deepak Malghan on caste bias in IIMs, noted: “In 1975, an exemption was granted to IIM Ahmedabad by the Department of Personnel and Training with respect to reservation in faculty positions. While IIM Ahmedabad had expressly sought this exemption, other IIMs simply assumed that they were also exempt and began not implementing reservations in faculty recruitment.”

Institutions have frequently justified the marginal representation of SC and ST faculty by arguing that there is a lack of a sufficiently qualified applicant pool, as reported by the Quint.

However, marginalised communities remain underrepresented in these institutions both as students and as faculty. They are subjected to grave mental harassment on the basis of caste identity, by peers, by authorities, and by colleagues. At the same time, institutions routinely deny the existence of discrimination and attempt to curb voices that raise these concerns.

The deeper truth is this: people from marginalised communities are seldom truly accommodated within these spaces. They are rarely made to feel that they belong. They are otherised – their culture, language, and food practices subtly or overtly looked down upon. In these elite institutions, they continue to remain “they,” never fully accepted as “us.”

UGC Guidelines: Context, Counter-revolt and protest

It is in this overall context of entrenched exclusion and othering that recent developments around the much-needed UGC guidelines 2026 need to be understood. Brought in following a rigorous human rights battle in the courts –spearheaded by the mother of Rohith Vemula and Payal Tadvi—they evinced visceral reactions from sections of the privileged caste elite. The union government, without putting up a spirited defence of its own enacted guidelines capitulated in its arguments of caste elite organisations in the Supreme Court. The Court too was prompt to stay implementation of these measures that would go a long way in addressing entrenched exclusion. Dozens of campuses across the country have seen spirited protests against this capitulation. Chandrashekhar Azad of the Bhim Army party even held a demonstration at Jantar Mantar on February 11 demanding that the 2026 Guidelines be implemented without change. Read references to this issue here, here and here.

Conclusion

“One out of three SC/ST students reported being asked about their caste,” revealed an IIT Bombay survey conducted in 2022.

Many students from the general category have reportedly hurled casteist abuses at SC/ST students. These elite institutions increasingly resemble exclusive spaces of savarna dominance. Yet, reports such as Caste-Based Enrolment in Indian Higher Education: Insights from the All-India Survey on Higher Education (AISHE) are published, claiming that nearly 60% of seats in higher education institutions are occupied by students from marginalised communities (p. 11 of 26).

While the AISHE data indicates a rise in enrolment from marginalised communities in recent years, it fails to answer a fundamental question: which institutions are being counted? Are these Tier 2 and Tier 3 colleges in urban peripheries, or institutions located in remote rural areas? Or are we speaking of IITs, IIMs, NITs, AIIMS, and Central Universities, the institutions that command prestige, resources, networks, and opportunity?

The distinction matters. A BSc degree from IIT Bombay can open doors to high-paying corporations and global opportunities. A BTech degree from an under-resourced college in a remote district often cannot. Access to elite institutions translates into access to power.

Meanwhile, over 13,000 SC, ST, and OBC students have dropped out of higher education in recent years. In Central Universities alone, approximately 4,500 OBC students, over 2,400 SC students, and nearly 2,600 ST students discontinued their studies. In the IITs and IIM’s, India’s premier institutes of learning — renowned not only for academic excellence but increasingly for caste discrimination and student suicides – around 2,000 OBC students, 1,000 SC students, and 408 ST students dropped out. At the IIMs, 163 OBC, 188 SC, and 91 ST students discontinued their education reported SabrangIndia.

The disbursal of fellowships and scholarships is frequently delayed, often reaching students only after the semester has ended. Students are made to feel undeserving and unwelcome—by faculty and by peers alike. They are shunned for their caste identities. They are made to feel like outsiders, as though these institutions belong only to certain classes and castes. Even their food practices are policed and mocked, as has been reported in several IITs. Sabrangindia has frequently reported on this alienation and discrimination.

Faculty positions in these institutions are overwhelmingly occupied, often 80 to 90 percent—by those from the general category. Those who dominate these spaces frequently go on to hire within the same social circles, reproducing exclusion in the name of “merit.” It becomes a vicious cycle. Even when scholars like Gopal Das or Subrahmanyam Sadrela manage to reach the other end of this black hole, the system finds ways to pull them back.

Nearly 79 years after Independence, sections of our people continue to be treated as second-class citizens within spaces that claim to represent the pinnacle of knowledge and progress. India prides itself on constitutional morality, yet its elite institutions often operate within what increasingly resembles an internal apartheid.

How long will this continue? How long will students like Rohith Vemula, Payal Tadvi, Darshan Solanki, and countless others be pushed into a system so steeped in humiliation and mental harassment that death appears to them more bearable than a life stripped of dignity?

That is the question we must confront.

(The legal research team of CJP consists of lawyers and interns; this resource has been worked on by Natasha Darade)

[1] A suicide born of distress, mental and other torture and alienation at the Hyderabad Central University (HCU) on January 17, 2026 inspired the Dalit students movement to coin the term “institutional murder” as this was the last of many and the beginning of several such deaths with institutions of higher learning in India

Related:

A Long Battle, A Swift Stay: The Fight for Equitable Campuses | SabrangIndia

My birth is my fatal accident, remembering Rohith Vemula’s last letter

Rohith’s death: We are all to blame

To Live & Die as a Dalit: Rohith Vemula