Barwani, Dhar (Madhya Pradesh): Two middle-aged men struggled to carry an old steel cupboard, which looked like it had never been moved, from a house in south-western Madhya Pradesh in central India.

Homes of fisherfolk in Chhota Barda village in Madhya Pradesh’s Barwani district, submerged at the 134 metre level of Sardar Sarovar Dam on August 27, 2019. The Madhya Pradesh government had warned in May 2019 that about 6,000 families would be submerged if the Sardar Sarovar Dam is filled to its full height of 139 metres. But the central government went ahead.

Clothes and kitchenware packed in old sarees were placed outside. The house next door in Nisarpur village was half submerged under the rising waters of the Narmada. The ground floors of most shops in a parallel lane were under water, and moss-covered. Streetlights stuck out of the water at odd places, as people scurried from one lane to another to help others load their belongings onto a pick-up truck.

On the other bank of the swelling river, in Chhota Barda village, four government officers hunched over a low table. Facing them was a queue of more than 100 people who stood clutching rolls of letters and documents that prove their identity.

As people walked to the table, the officers noted down their names and asked questions to determine why they had not left the village–they should have been rehabilitated long ago because their village fell in the submergence zone–a large area which would be flooded once the Sardar Sarovar Dam, about 140 km away in the neighbouring state of Gujarat, was filled up to its full height of 138.68 meters, roughly as tall as a 40-storey building.

Officials assess the number of people living in submergence areas at an impromptu state government camp on August 28, 2019, in Chhota Barda village in Madhya Pradesh’s Barwani district.

As the rains arrived this year, the central government decided to completely fill up the dam for the first time since its construction was completed in 2017, letting the Narmada’s waters rise. When the water level touched a record 134 meters on August 28, 2019, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi put out a tweet describing the water level as “historic”.

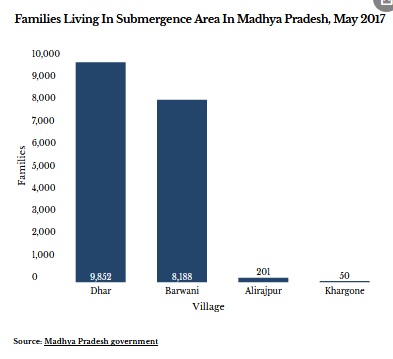

The Modi government has claimed since 2014 that every single family from the dam’s submergence zone has been rehabilitated at new locations. However, as our reporting from Madhya Pradesh shows, at least 6,000 families–based on the state government’s own estimates–have been living in the soon-to-be submerged area in the state, waiting to receive final rehabilitation payments. The central government knew about these families when it decided to fill the dam to capacity, from a letter the Madhya Pradesh chief secretary wrote to the Centre in May 2019, which IndiaSpend has reviewed.

Across villages along the Narmada, people continue to live in houses which will be partly or fully submerged once the water level in the Sardar Sarovar dam touches 138.68 metres.

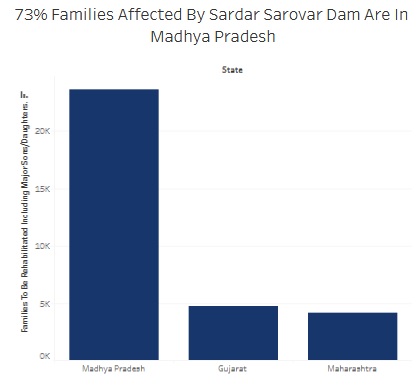

The Sardar Sarovar Dam, which is expected to irrigate farmlands in arid western Gujarat and Rajasthan, and generate electricity for Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra, has faced one of the most persistent and iconic anti-dam struggles in the country, and indeed the world.The dam is estimated to have displaced at least 32,000 families from their homes in the river-side villages of Gujarat, Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh, 73% of the total families affected being in Madhya Pradesh.

Source: Narmada Control Authority

There is “not a single success story” of rehabilitation in the history of large dam projects in India, said Himanshu Thakkar, coordinator of the research organisation South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People. “They expect people to move away or be evacuated for law and order,” he said. Earlier, Pong Dam in Himachal Pradesh was filled up without full rehabilitation of the people affected, he said. “At that time, [cabinet minister] Morarji Desai had publicly told people that the dam was going to be filled up and it was in the people’s best interests to move out on their own.”

As the Narmada swelled and flooded homes–and photographs began to circulate on media–the government of Madhya Pradesh swung into damage-control mode. It set up camps such as the one in Chhota Barda village in Barwani district that we visited, where hundreds had turned up to complain about incomplete rehabilitation, though it was supposed to conclude by June 2005, as per the estimate of the Narmada Control Authority, a central government agency that is responsible for operation of dams on the Narmada and the rehabilitation of the families affected.

On September 5, 2019, a video tweeted by Narmada Bachao Andolan showed a displaced person, from Dhar district, who had attempted suicide.

On September 3, 2019, the Madhya Pradesh government called for an urgent meeting, warning that “there is substantial amount of relief and rehabilitation going on in the affected areas of Sardar Sarovar”.

Why people could not leave

Most of the houses in Chhota Barda, where the Madhya Pradesh government (now led by Congress party) has set up the camp, had numbers written in red near their doors to indicate where the river water would reach once the dam was filled to its full height of 139 m.

A few meters away from the camp, 50-year-old Ramesh Jadam weighed his options as the Narmada inched ever closer to his two-room mud-walled house, where he lives with nine family members including three sons, one daughter and a grandson. His doorstep read 139.

In 2008, the Madhya Pradesh government, then led by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) for three years, which would remain in power in the state for another seven years, allotted Jadam a 5,400 sq ft plot in a nearby resettlement area to build a house. The plot is almost as big as his current house but he received only Rs 1 lakh as compensation, he told IndiaSpend, an amount barely enough to lay the foundation of the new house.

So, Jadam said, he waited for another compensation package of Rs 5.8 lakh that the state government announced in 2017. That amount never reached him. So he could not leave the village.

Ramesh Jadam, 50, weighed his options as Narmada waters inched ever closer to his two-room mud-walled house in Chhota Barda village, where he lives with nine family members. In 2008, Jadam was allotted a 5,400 sq ft plot in a nearby resettlement area, but he received Rs 1 lakh in compensation, which he said was inadequate. He continues to wait for the further Rs 5.8 lakh that the Madhya Pradesh government announced in 2017.

Neighbours in a house down the slope were evacuated by the local administration in a frenzy one week before we visited on August 27, 2019. Jadam’s family is the only one left in this part of the village. “It looks like they [the government] have given up on us,” he said. He would have nowhere to go to when the waters reached his doorstep.

The Madhya Pradesh government scheme that Jadam was waiting for was the government’s last attempt at concluding the long-awaited rehabilitation for people affected by the Sardar Sarovar dam. According to a central government order of 1979, all affected families are entitled to alternate land for housing and agriculture. Apart from this, families are entitled to cash compensation for their lands based on the Land Acquisition Act, 1894, and other cash benefits. Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, and Maharashtra, over time, extended additional benefits to the people being rehabilitated within their territories.

In 1994, seven years after construction of the dam began, the Narmada Bachao Andolan filed a writ petition in the Supreme Court asking for the dam to be scrapped. They expressed concern that thousands of families would be rendered homeless.

The court, however, ordered in 2000 that the project would continue but only after people living in the corresponding submergence area were rehabilitated. For example, to build up to 100 m, the government would have to complete the rehabilitation of all the families whose homes and lands would be submerged at that water level.

Over time, most families received alternate land for housing, but the cash compensation was too little for many families to build houses there, so they continue to live where they were. In May 2017, just a month before the central government ordered the floodgates closed to fill the dam to capacity, the Madhya Pradesh government published a list of 18,000 families that were still living in the submergence area, and in August that year, announced a special cash package of Rs 5.8 lakh to each family.

Some received it, some did not. During our visit, the villagers showed us letters from the state government dated August 16, 2019, addressed to about 20 families in Chhota Barda informing them that they would be paid the amounts soon. This was when dam waters were already entering their homes.

Jadam did not receive the amount, he told IndiaSpend.

Damage control

In Chhota Barda, people who had not received the Rs 5.8 lakh package included fisherfolks who lived closest to the river. When the dam began to fill up, the local administration sent pick-up trucks to evacuate them. Their goats, chicken, utensils, boxes and other household effects were loaded on the trucks and transported to the rehabilitation area in the neighbouring town of Anjad.

Here, about 100 families now live in rows of sheds constructed out of corrugated metal sheets. The local government gives them three meals a day, but people have no source of income.

“The food is alright. But what kind of a life is this?” said Gaju Nanuram, a 65-year-old fisherman. “We have no money or work. It is like living in a jail.”

About 100 families now live in sheds made of corrugated metal sheets in Anjad, after being evacuated from their homes in Chhota Barda as the Sardar Sarovar dam began to fill up. The local government gives them three meals a day, but people have no source of income.

The district collector, Amit Tomar, said this was a temporary measure to house people who had nowhere else to go. He said rehabilitation is the responsibility of the state government and the district administration is evacuating people whose houses were going to be submerged so as to prevent the situation from getting out of control.

One government employee managing the site said they had no definite orders from the government about how long the camp would be run. He requested not to be named.

The central government knew there could be crisis on the ground but still decided to fill up the dam, official documents show.

In May 2019, following the demand by the BJP-led Gujarat government that the dam be filled to capacity to conduct safety testing, the chief secretary of Madhya Pradesh wrote to the Narmada Control Authority (NCA), that 6,000 families continued to live in the submergence area of the dam, while another 10,000 families’ cases were still being heard at grievance redressal forums. IndiaSpend has reviewed this letter.

The number of people still living in the submergence area as per the chief secretary’s letter is at odds with that of the NCA. Way back in 2015, the authority had declared that all 32,000 families affected by the dam had been rehabilitated. Its website still states that there are “nil” families remaining to be resettled.

The minister for Narmada Valley Development in the Congress party’s Madhya Pradesh government, Surendra Baghel, has alleged that he discovered that the earlier government had misreported the ground situation and had in fact not sought the necessary funds from the Gujarat government.

Medha Patkar, convener of Narmada Bachao Andolan, alleges that even the present Madhya Pradesh government has not taken action against those who had reported the “zero balance” figure. “What was the meaning of that figure when they were still giving out compensation [in 2017]?” she told me.

Patkar was on an indefinite hunger strike near the river in Chhota Barda when we visited. She had demanded that the floodgates of the dam be opened and the rehabilitation process be completed. On August 28, 2019, Madhya Pradesh home minister Bala Bachchan came along with the district collector to the camp to assure Patkar that the state cabinet would meet soon to take “whatever decisions are within our power”.

“When you were in the Opposition you sat with us in protest,” Patkar replied. “But now you are not showing the same energy.”

It is only the Narmada Control Authority that has the power to decide whether to open the floodgates or to let the dam fill up as per schedule. Documents that IndiaSpend reviewed showed that the authority has approved the filling up of the dam to its full level by October 31, 2019.

Mismanagement at Narmada Control Authority

The Indore-based Narmada Control Authority, which is headed by the secretary of the central government’s department of water resources, has four members including one executive member. One of them is supposed to be appointed by the central government to oversee the rehabilitation process. This post has remained vacant since April 2019 and is currently held as an additional charge by Suman Sinha, who also holds the charge for three of the four member posts.

She declined to meet with IndiaSpend, as did Mukesh Sinha, the executive member. Neither responded to a detailed questionnaire sent to them. At the authority’s office on August 29, 2019, officers scurried in and out of meeting rooms. They had received a letter from the Centre’s water resources department to answer the allegations raised by the Narmada Bachao Andolan, including the fact that thousands had not been rehabilitated. The letter, which IndiaSpend saw, was marked “TOP PRIORITY”.

Meanwhile, homes continue to be submerged as the dam level rises. “It is impossible to believe this,” said 42-year-old Suresh Pradhan, a shopkeeper in Nisarpur village, which has the highest number of Sardar Sarovar dam-affected persons of any village in Madhya Pradesh.

Suresh Pradhan (in blue shirt) gestures towards the market in Nisarpur, Madhya Pradesh, where his shop lies submerged.

Pradhan said that although the additional compensation package of Rs 5.8 lakh may seem little to build a house, every adult member of a family was entitled to it. So a family with one father and three other adults would receive Rs 23.2 lakh. Pradhan too was waiting for the money, but he was told last month that he was not eligible because his house was just a few metres above the submergence level, which is marked in yellow on the road.

The two-storey house his great-grandfather had built would be like an island surrounded by water, Pradhan said, and there would be no point living there.

The local school had shut down some time ago, and he had been told that water and electricity supply would be cut off too. “Now they [government] say that I am not eligible for package because my house will not submerge,” he said. “But believe me, when the waters rise they will come in boats to evacuate me.”

Suresh Pradhan (right) stands outside his home that was built by his great-grandfather. The yellow mark on the road shows where the water would reach once the Sardar Sarovar fills to capacity.“Now they [government] say that I am not eligible for package because my house will not be submerged,” he says. “But believe me, when the waters rise they will come in boats to evacuate me.”

Back in Chhota Barda, the officers at the rehabilitation camp said the camp would be extended for a couple more days given the large number of people turning up. “This is just for show,” Vikram Singh, who had come to get his name added to the list of people yet to get the complete rehabilitation package, told IndiaSpend. He sat on the ground with his papers because there was no more space in the queue. “They have all our names already but still make us come here to repeat.”

An officer who overheard this glared at Singh and told him that he should have been satisfied with the Rs 1.5 lakh compensation he had received 10 years ago. “My father built a house for that much, that too near Indore,” the officer argued.

Singh looked agitated. “They just want to fill up the water, so that once and for all we will be gone,” he said. “Like getting rats out of a rathole.”

(Nihar Gokhale is a writer with Land Conflict Watch, an independent network of researchers and journalists documenting ongoing land conflicts across India.)

Courtesy: India Spend