The invaluable contribution of communist writers and poets to early Hindi cinema

Early Hindi cinema wins many accolades – for its idealistic themes, for its propagation of Hindustani and for its secular temperament. While it is true that the political atmosphere of the 1950s and 1960s, the Nehruvian era, was responsible for many of these attributes, the contribution of communist writers and poets to early Hindi cinema and to its idiom, language and content is often forgotten.

Obviously, a medium like cinema which is so responsive to public demands and public tastes does reflect its social and political context to a large extent. Therefore the values and excitement of the national movement, the heady brew of freedom from colonial bondage and the novelty of nation building and Nehru’s secular, modern outlook provided much of the inspiration for the best-remembered films of the era. But they would have been incomplete without the contribution of a galaxy of communist literary giants who chose this medium precisely because it was the most effective medium of mass communication.

It is important to remember that there is a basic difference between the way in which a communist uses the word ‘mass’ and the way others do. A communist uses the word with a feeling of reverence and respect and wishes to communicate with the mass in order to imbue it with what he considers to be the highest values and ideals and in order to help it achieve its historic mission to bring about universal equality. Others use the word mass contemptuously, in a pejorative way, with the objective of converting as much of it into mindless consumers of their products, including cultural works, as possible.

It was this attitude towards the mass combined with their enormous talents that made the communist contribution to early Hindi cinema so memorable.

Perhaps no country in the world has at any time in its history witnessed such a large number of first-rate talents harnessed to a common ideology. It is important to remember that communist writers, poets, actors and artists did not come from Hindi and Urdu backgrounds alone. All Indian languages were blessed by similar practitioners at the time.

They were all products of a unique blend of nationalist and revolutionary fervour that was peculiar to the 1930s when most of them came of age. This was complemented by the fact that many of them came from feudal and traditional families. For them the Communist Manifesto, the experiences of Soviet Russia and the national movement in their own country fused into liberating images far removed from the suffocating conservatism surrounding them. Patriarchy, feudal oppression, caste hierarchies and inhuman cruelty would all be blown away by the winds of change that they had not only begun to experience but which they themselves would fan into invincibility. This was the dream they dared to dream – not alone but in communion with each other, with their comrades – and which they longed to communicate to the masses.

Bombay, the working-class capital of the country, was the headquarters of the Communist Party of India. Its journals attracted the finest talents in the country. Sajjad Zaheer was able to bring writers and poets of the calibre of Kaifi Azmi, Ali Sardar Jafri, Jan Nisar Akhtar, Krishan Chander, Sahir Ludhianvi, Majrooh Sultanpuri and a host of others to work as party whole-timers. Without compromising the quality of their work they had the opportunity to test it every day against the touchstone of the people: the textile workers of Bombay, the handloom weavers of Bhiwandi, the fighting peasants of Bhiwandi.

It was this unique circumstance that would stand them in good stead when they brought their thoughts and verses from the world of cramped party offices, factory gates and vast public recitals to the world of cinema. Here they were joined by other comrades from the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) who gave Hindi cinema many of its earliest and finest actors and actresses.

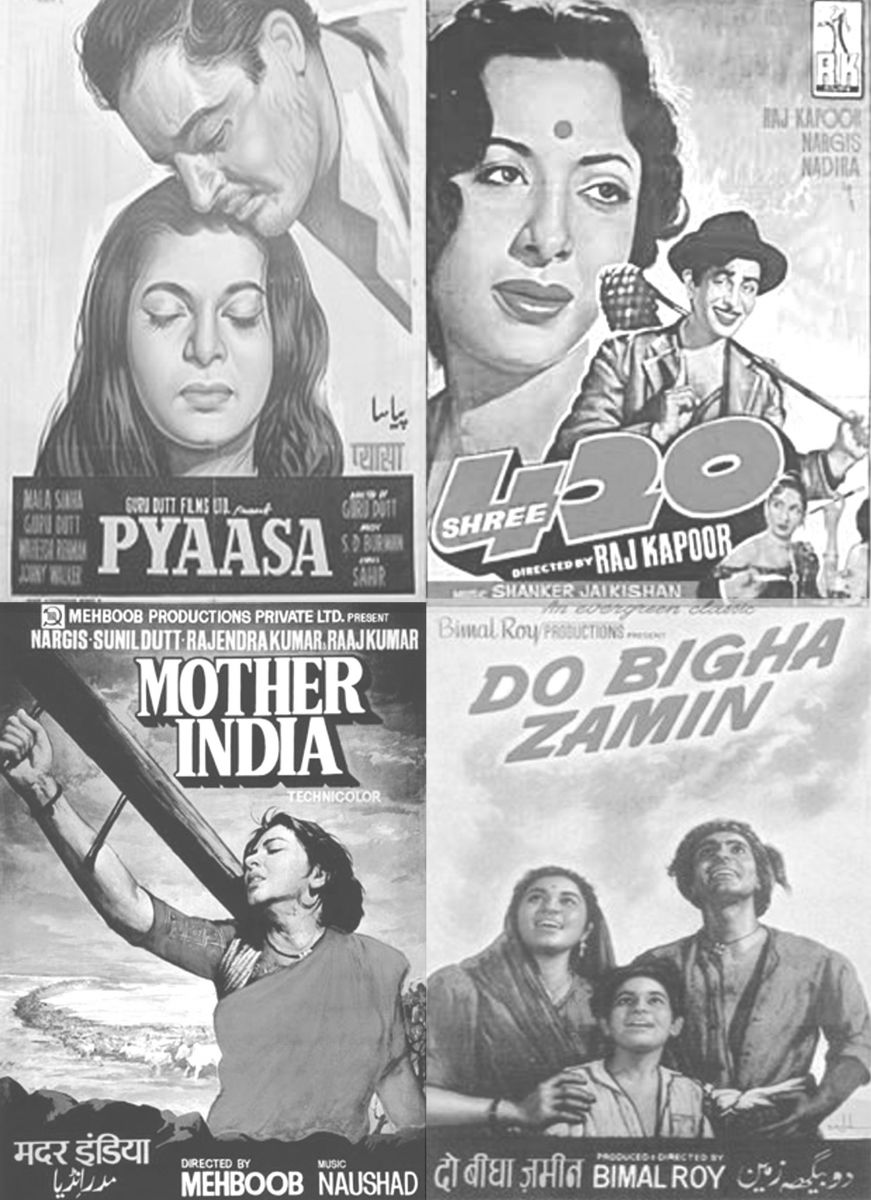

A New World. The New Woman. These were the hallmarks of what is nostalgically referred to as the golden era of Indian cinema. Awara. Shree 420. Mother India. Pyaasa. Do Bigha Zameen. The era’s sheen was provided by the communists. Of course, their convictions underwent changes with the years but their commitment to secularism and to its language, Hindustani, never diminished. And the dross of crass commercialism could never completely dull the brightness of their earlier dreams…

Archived from Communalism Combat, September 2008. Year 15, No.134, Cover Story 5