Man is memory. We are nothing but the sum total of our past. We are never free of the past. Karl Marx was a Christ returning to a modern world. In other words, he was the resurrection of basically the same religious spirit and ideology, although under a different garb, a different language. It could not have been otherwise. For not only Marx but all thinkers cannot help but build their philosophy upon their past. To put it differently, as a very famous French thinker, Jacques Derrida would say, to be means to inherit.

All questions about being or what one is to be or not to be are questions of inheritance. We are inheritors, like it or not. If you read The Road Ahead by Bill Gates, you will see it is more history than prophecy. That is why imagined futures are always more about where we have been than where we are going.

In the year 1951, two years after I was born and much, much before you all were even thought of, Jawaharlal Nehru compelled Purshottam Das Tandon to tender his resignation and took over as president of the Congress. Purshottam Das Tandon had defeated the secular factions of the Congress the year before, to become its president in 1950. In the newly "partitioned" India, Purshottam was a symbol of the communalist and revivalist outlook. Shattered by the irreversible loss of Gandhiji, who had been killed by the bullet of a Hindu fanatic fundamentalist, Nehru had sworn to go for the jugular of the fundamentalists.

At a public meeting in Delhi on Gandhi Jayanti Day in 1951, Nehru proclaimed his secular credo. He said, "If any person raises his hand to strike down another on the ground of religion, I shall fight him till the last breath of my life both as the head of the government and outside." This statement sums up everything that needed to be said about the spirit India and future Indians must have towards secularism. And this spirit was ignited in 1951, by Nehru, the most extraordinary jewel that India ever possessed.

Post-Independence Hindi cinema fashioned its products on this passionately articulated creed of Nehru. A glowing example of this is Dilip Kumar. He is an excellent symbol of secular India. The recent revival of Mughal-e-Azam and its global success proves that the pendulum of public taste has once again swung towards films that celebrate the pluralism and the secular creed of free India and has moved away from movies like Gadar, which in a very subtle manner demonise the

Muslims, and not just Pakistan.

The new colour version of Mughal-e-Azam was happily lapped up by children of the current generation. My daughter and my young son were both mesmerised by what our ancestors had achieved in those days, both in spirit and also on the screen. My heart just swells with pride when I watch Mughal-e-Azam. It reminds me of what Bollywood once was. Do you know that this magnum opus was made by an almost all-Muslim crew? It was produced and directed by K. Asif, and it had Madhubala and Dilip Kumar in the main lead. And above all it had Naushad, the music director who’s soul resonated with Hindu bhajans. How can India and Indians ever forget ‘Mohe panghat pe Nandlal chhed gayo re’, a song from Mughal-

e-Azam in which the birth of Krishna is being celebrated in the court of Emperor Akbar and in which Madhubala, an actress who is Muslim by birth, dances like Meera?

The phenomenal success of Mughal-e-Azam today has also demonstrated that despite all the efforts of the previous regime to strangulate the secular voice of India, India’s secular spirit is very much alive and kicking. Because if this was not so, Mughal-e-Azam wouldn’t have been a box office hit.

Recently I was told by the ministry of Information and Broadcasting that Mughal-e-Azam was also screened in the Srinagar Valley, where Hindi movies have not been playing for years. The major bulk of the audience consisted of young people of your age. Now, ever since trouble began in Kashmir, the young people of that region have been violently opposing anything "Indian", even Hindi movies. The cinema hall where the film was now being shown was earlier forced to close shop because no one came to the hall to watch Hindi films. But Mughal-e-Azam had shocked everybody. Not only was it running to packed houses, but all those young people who came to watch the film clapped and applauded all through it. This is the Bollywood that I was born in. This was the Bollywood whose films every Indian right from Kashmir to Kanyakumari watched and loved.

I remember my father, a filmmaker who made more than 100 films. Many of these films were based on The Arabian Nights fantasies. Now my Dad was a Brahmin but despite that, surprisingly, he knew more about Islam and the Islamic culture. My mother was a Shia Muslim. I remember after finishing her namaaz she would tell us, my brother, my sister and me, tales from Hindu mythology. These stories still resonate in my heart. One of these stories was effectively put to use by me in my film Raaz. The climax of Raaz was sourced from a tale my mother told me about Savitri and her fight with the Lord of death, Yama, to bring her husband back to life from the jaws of death.

The Bollywood that I grew up on had jewels like Sahir saab (Ludhianvi). Sahir saab is the greatest lyricist Bollywood has ever known. He is a Muslim who decided to stay in a secular India after Partition. The most enduring bhajan of all times, ‘Allah tero naam, Ishwar tero naam’ was written by this extraordinary poet. Even a great filmmaker like Guru Dutt worked with people like Kaifi Azmi and Abrar Alvi. Chaudvin Ka Chand, produced by him and directed by M. Sadiq, is the best film made against the backdrop of Lucknow and the Muslim tehzeeb (culture). Most Hindu filmmakers of those times made these films dealing with the Muslim culture without any self-consciousness. They made these films because that culture was a part of them. The filmmakers of those days had the best of both cultures in them – no wonder that age is called the golden age of Hindi cinema.

I remember the last scene of Ganga Jamuna in which Dilip Kumar dies saying "He Ram". Most people who saw the film then felt that the reverence with which this Muslim actor had uttered He Ram reminded them of Gandhi’s last moments. Cinema goers imagined this was how the Mahatma must have died. However, Ganga Jamuna faced severe problems when it was seen by members of the censor board. Some board members who had communal leanings wanted to delete this very scene saying that they could not have a Muslim saying "He Ram". In spite of being secular to the core, Dilip saab faced many problems from both within the community and outside it. He was the prime target of all those people who had designs to revive the religion of the majority and destroy the pluralism of India. But Dilip saab did not bow down to these forces. He stuck to his guns and remained a symbol of secularism for all of us.

The recent revival of Mughal-e-Azam and its global success proves that the pendulum of public taste has once again swung towards films that celebrate the pluralism and the secular creed of free India and has moved away from movies like Gadar, which in a very subtle manner demonise the Muslims, and not just Pakistan

Recently I ran into Subhash Ghai and our conversation, after having spoken about the current state of Bollywood and what we should to do to stay afloat, slowly turned to the topic of Dilip Kumar and the need to immortalise him and put him on film because the man should be given his rightful due in history. He has been a reluctant icon because of which a lot of bogus icons have been enshrined on the altar. Dilip saab is a symbol of secularism; all his life he in fact echoed what Nehru spoke of. It was very moving to see a man like Subhash Ghai, otherwise known only for masala films, dedicate himself to make a documentary that would outlive this legend. I had begun my career as an assistant director with the great filmmaker, Mr. Raj Khosla, with a film called Do Raaste, a box office hit. The film contained a sympathetic portrayal of a Pathan played by Jayant.

Now, this was a device commonly used in most Hindi films. Most of these roles were ineffective since they were insensitively projected on the screen. But some producer-directors who came from the North and who had lived with the Muslims there and enjoyed their hospitality and warmth portrayed these Muslim characters on film brilliantly. Do Raaste became a very big hit because of this noble Muslim character. A great scholar of Indian music said to me recently, "You know, the difference between Indian music and Indian film is that Indian filmmakers did not portray secularism and pluralism as brilliantly as the music directors and the lyric writers did." Somewhere, our Indian filmmaker was very simplistic, he did it as the politician does – Hindu-Muslim bhai-bhai, using the ‘hugging each other, making tremendous sacrifices for each other’ formula. But it was in fact the music directors and the lyric writers in whose hearts were crucibles from where the pluralism that we keep talking about poured in and they made those wonderful tunes and songs. Ultimately music seeks to evoke some emotion in you. The ghazals and the tradition of thumris, and khayaals, the complete mixture of tehzeebs is what India is all about and that was what they portrayed through our music. I remember when I was growing up, my father made a film called Mr. X with a rock and roll number called ‘Lal lal gaal’ – a number that was a huge hit. This shows how much the Christian influences contributed to the success of our Hindi films in those days. Helen, a Christian by birth, was the heartthrob of the nation. She cast her spell on the people of India for almost two decades.

I began my career in the year 1973 but came into the limelight with films like Arth, Saaransh, Naam and Janam. Most of these films were sourced from one’s own life. They were autobiographical. But it took a tragedy like the demolition of the Babri Masjid and the subsequent bloodshed of innocent Muslims on the streets of Mumbai to hurl me into my hidden past and make my last directorial film, Zakhm.

I came from the home of a Hindu Brahmin father and a Muslim mother and had the good fortune of being educated by Christian missionaries. It is because of them that I can stand here before you and speak in the language that I speak. The demolition of the Babri Masjid made me realise the naked truth that what is personal is political. When Mumbai burnt, I recalled that I too was subjected to a lot of humiliation by those very forces that were now unleashing their wrath against the minorities. When I was a child my paternal grandmother, who was a Hindu fundamentalist, had spared no opportunity to brutalise my mother and me simply because my mother was a Muslim. After having found dizzying success and after making senseless and meaningless movies, the time had now come to make the defining film of my career.

I am glad that before I hung up my gloves as a director (I continue to produce films and write them), I dared to revisit the wounds of my childhood. I told a tale that moved out into the larger domain, the public domain – the post-Babri Masjid demolition period and the subsequent bloodshed. This was Zakhm. I dared to make this film with my own funds, without State help, in a very repressive atmosphere. This was in 1998. My daughter Pooja produced Zakhm at a time when it was considered suicidal to make films that dared to incur the wrath of the Hindu fundamentalists in Delhi.

Scene from Zakhm

There is a particular scene in Zakhm where the character played by Ajay Devgan slaps his brother who, unaware of his mother’s religion, her faith, is about to go and kill a Muslim boy who had burnt his mother alive. Ajay Devgan strikes him and says, "Yeh tere baap ka mulk hai kya?" (Is this your father’s land?) And says, "Kisko nikalega? Inko nikalega, kyon? Kyon ke ye Musalman hai?" The manner in which he strikes him reminded me of Nehru’s statement of 1951 when he said, I will fight till my last breath against all those forces who will raise their hands against anybody in the name of religion – It was then that I discovered that through the virtual world, through movies, the same spirit of Nehru was somewhere expressing itself. That’s what I meant – to be is to inherit. I had inherited the sanity of the founding fathers and it was being expressed unapologetically there on the screen. In fact, recently they showed a short documentary, a half-hour programme on me on the BBC where they had, without my telling them, shown this particular portion of the film – where one brother strikes the other and says he will fight till his last breath to see that India celebrates its pluralism. So things had come full circle. This apathetic man, this little boy, who was born in a home like this, who had moved far away from it and had gone into making escapist films, the man who had forgotten Mughal-e-Azam, but was traumatised when Bombay bled, finally made the only defining film of his career. Zakhm had bought me a lot of dignity. It washed me clean, it purged me of the aftertaste of having made some senseless films. If Zakhm is still a part of public discourse today, that is because it carries in its core the sanity that Gandhiji and our founding fathers spoke about, fought for and died for.

According to me, the first rotten phase that Bollywood saw was when, under the name of demonising Pakistan, a lot of movies actually took perverse delight in mocking and ridiculing the Muslim community. It was a phase after which the public, having made one odd film into a big hit, themselves boycotted such films. And it is unlikely now that any such films will be made since they do not run at the box office anymore.

That remains the saddest, most shameful chapter in the history of Bollywood, which had otherwise been very secular and had always celebrated pluralism. This only means that just as Nehru’s creed was reflected in the movies for 40-50 years, it was Nehru’s ideology that sparkled in our movies. Because, being what they are, leaders inspire filmmakers to echo what they feel. When the right wing Hindu fundamentalists came to power, they could only pass on their perversion to filmmakers, encouraging them to make movies of a new kind of genre, movies that made some sort of noise temporarily, but a noise that the people of India rejected. This was the sanity of this nation. This was secular India.

As we have stepped into the 21st century and we have now thankfully de-linked ourselves from that painful phase, we must be very cautious that the same forces that destabilised India in 1992 and once again in Gujarat in the year 2002 are very much alive, active and dying to get back and reassert themselves. They were there in 1951 when Nehru had to fight them; within the Congress Nehru had to fight his own people to assert secularism. The secularists of the nation must lock horns very aggressively with so-called communalists. I don’t believe in the passive stance that people take. I have always maintained that society is not devastated by the misdeeds of the bad man but by the silence of the so-called good people. It is when you and me are silent that we devastate society.

You are on the threshold of a great career. You’re going to go there, into the trenches of life. During a conversation with N. Ram, the editor-in-chief of The Hindu a while ago, he said that the danger of the times is that we in institutions give our people a lot of skills and those skills certainly help one to make it in life. But what you need is an educated mind. A mind which has a broader view, which understands that whatever we do or whatever we see, will have far-reaching consequences. What you need is integrity and commitment; you need commitment to those very sane values that have seen us through. Values that are not negotiable, irrespective of the troubles we go through. You cannot negotiate the core value of India’s commitment to the secular creed. How can you do so? It would be akin to suicide. Take me for instance; when I look within myself, half of me is a Hindu, the other half a Muslim. Which part of me can I break away from without killing or destroying myself?

You are about to begin a new journey as the filmmakers and journalists of tomorrow. So it is important to remember what is being articulated here. Maybe the subject is so huge that it’ll take us lifetimes to discuss it. But essentially what I hope to do is ring an alarm bell. Just as I woke up after the carnage in Mumbai, after 1993, and discovered that I must dedicate myself and support platforms and movements like these. Otherwise I am in danger of destroying all that India stood for. The fight that Nehru waged has to be continued by me in the virtual world and through platforms like this. And you, as filmmakers, journalists, need to continue this too. For, if India moves away from a secular creed it will disintegrate into chaos and destroy everything that it has with such difficulty built.

Let anybody rule us, but they cannot divide this country under the name of religion. And this is what we must pledge to work for. As filmmakers, as writers, as simple people who make a day-to-day living, this is one pledge that we must make. And on behalf of Bollywood, I have said that Bollywood has made a significant contribution, but as for its aberrations, forgive them my Lord for they know not what they do. There was a dark phase where they became ignorant, when the bosses asked them to bend and my brothers began to crawl. So forgive them, there were a few who made mistakes like this, but I thank god that a new dawn is here and I thank god that with you people going out into the field you will never ever let that happen again. Amen.

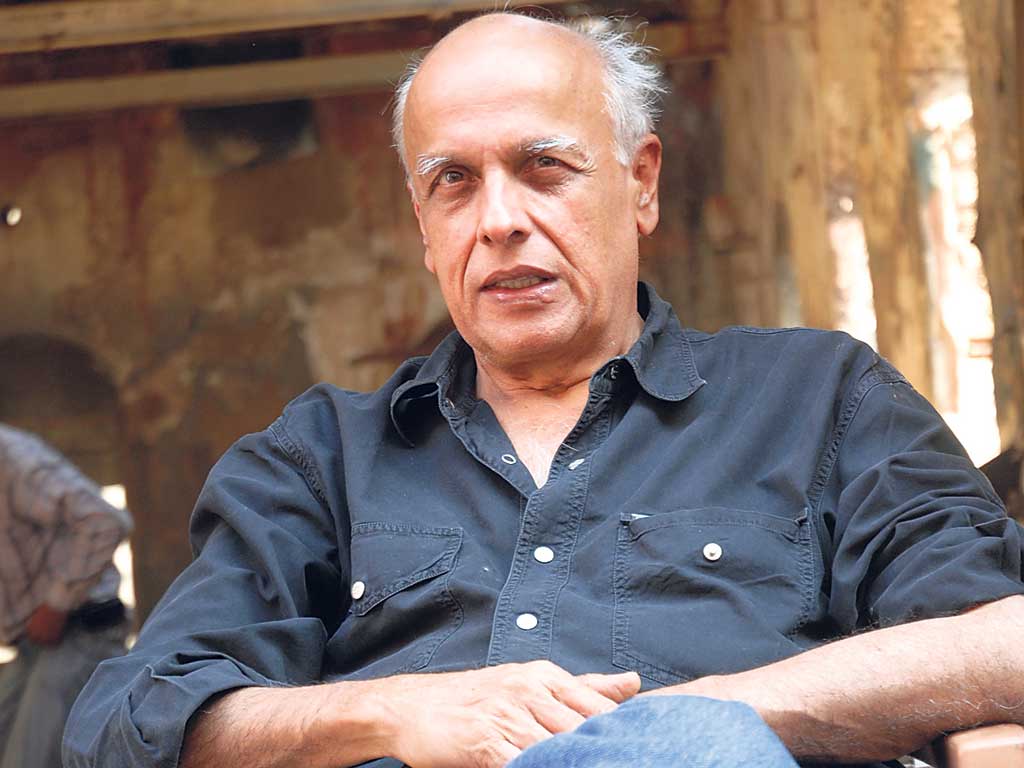

(Mahesh Bhatt is a well known film producer and writer, and former director of several Hindi films).