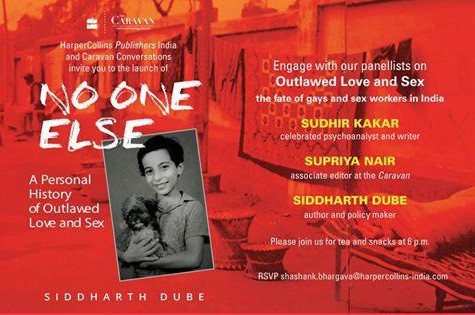

Reviewing Siddharth Dube's No One Else, A Personal History of Outlawed Love and Sex

"Once again I was a criminal in my own country, an outlaw for being who I was, with little hope for freedom in my lifetime."

In most reviews about books, to begin with the closing line would be considered sacrilege. In this case though, this final anguished statement about the re-criminalization of homosexuality in India stands as a brief comma punctuating a much larger journey that is far from over. The Supreme Court of India's Suresh Kumar Koushal judgment that effected this re-criminalization in December 2013 was a widely derided move, inciting outrage, both domestically and across the world. It is also, in Siddharth Dube's account, one of the more recent chapters in a story that spawns decades, that brings together a massive range of actors, and one that intersects with the story of other movements.

It is these stories that Dube sets out to explore in No One Else: A Personal History of Outlawed Love and Sex. The book begins as an intimate account of a gay man's tentative coming out process, his struggles with his femininity in male-dominated environments at school, his gradual emancipation as he moves into less regimented spaces, and his eventual joyous discovery of sex. Gradually, the breadth and scope of the story expands as it sweeps through crumbling slums and glittering international corridors of power. The narrative finally revealed to us is the contemporary history of three major intersecting movements – sex worker rights, rights of persons living with HIV/AIDS, and LGBT rights – as seen through the eyes of the author.

The most remarkable factor about Dube's sweeping accounts is how he ensures there is a personal core at the heart of these stories. Statutes and policies, both national and international, hold a vast potential to obfuscate and reduce the sum total of human complexity into reams of dry language. This book cuts through the haze of such officious language to tease out the damning impact that such innocuous looking texts, particularly as witnessed in international policy documents, have on the domestic stage. Dube's pen is keen and unsparing in his attacks – particular scrutiny is reserved for the Bush administration's disastrous policies relating to HIV/AIDS and sex workers rights that in turn pushed creditable institutions like UNAIDS into vastly diluting their commitments on both fronts.

There is at least one intersecting oppressor in the struggles faced by LGBT individuals, by persons living with HIV/AIDS and by sex workers: the idea of sexual shame. ….. And it is this shame that ultimately requires HIV/AIDS to be recognized as a human rights issue in a manner different from prior epidemics, as persons afflicted with it face an incomparable stigma.

This personalizing narrative comes through most powerfully in his account of the AIDS Bhedbhav Virodhi Andolan's report on rights violations faced by the LGBT community. A document harking back to 1992, Less Than Gay is widely considered to be the first report to highlight human rights abuses faced by the community as well as providing a blueprint for legal and social change. In Dube's hands, the report becomes a space for the re-imagination of the domains of what is possible. It also stands as a labour of love, a final rage against the dying light from the remarkable activist Siddharth Gautam, whose life was tragically cut short by terminal illness.

Another thematic element that foregrounds the book, but is never actually mentioned by name, is the idea of intersectionality. This oft used and abused term has soaked into contemporary rights speak, but continues to be understood more in its absence. The question often arises: how does one do intersectionality? This might be asked along two routes: First, how one might effectively inculcate an intersectional approach, and second, how one might push oneself to internalize this ideal.

For Dube, the first aspect comes from locating points of commonality. There is at least one intersecting oppressor in the struggles faced by LGBT individuals, by persons living with HIV/AIDS and by sex workers: the idea of sexual shame. It is this shame that stalks the author in his own inability to deal with his sexual desires even as he comes out of the closet. It is this shame that explains why sex workers face such massive opprobrium right to the international level, even as client numbers continue to thrive. And it is this shame that ultimately requires HIV/AIDS to be recognized as a human rights issue in a manner different from prior epidemics, as persons afflicted with it face an incomparable stigma.

If we can understand intersectionality through abstraction, we can internalize it through empathy. Dube finds himself sharing a strong commonality with sex workers for instance, " … intellectual as well as personal. Sex workers and gays seemed to share the fate of being demonized because of commonplace prejudices about sex. People thought of us as immoral, driven to sin by greed or lust. While sex workers sold their private parts for money, gays defiled theirs out of unnatural lust." Empathy and the quest for justice isn't merely a route that is facilitated by one's experience of marginalization: it becomes an act of healing the self as well. As Dube notes early on, his work on social justice issues in turn bolstered his nascent feelings of self-respect and self-worth.

Dube's final words, his despair at re-criminalization, might strike one as a bleak note to conclude on. But we only have to recall Martin Luther King's words: "The arc of the moral universe is long and bends towards justice". It isn't a clear progression, this arc of justice, as we see in the massive pushback on sex workers' rights following a period in the late nineties when sweeping reforms seemed to be on the horizon. And yet, many setbacks are hidden milestones. The Koushal judgment for instance led to sustained discourse on the issue, even causing a range of political parties to come out with supportive statements on the issues. Just last week, the Lok Sabha voted against even discussing Shashi Tharoor's private members' bill to amend Section 377. As dispiriting as this move was, it also generated a great amount of public debate on the matter, and may yet galvanize civil society further.

Siddharth Dube's book then becomes both, an important chronicle of struggles by sexual outlaws, and an impassioned testament in the continuing stage for the battle for social justice.