Kehtey hain agley zamaane mein koi ‘Mir’ bhi tha

You are not the lone scholar of Rekhta (Urdu language), Ghalib

They say that in olden days there was a ‘Mir’ too

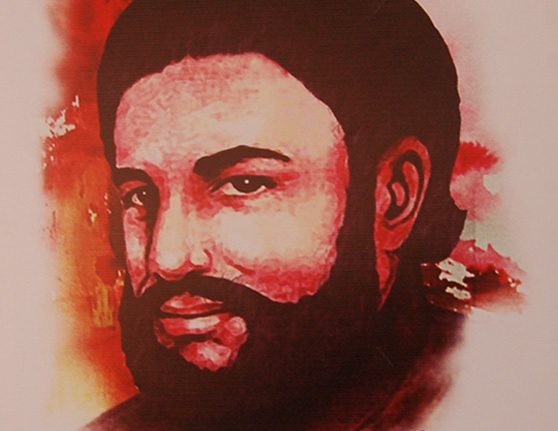

As Delhi fights an ongoing battle with hatred, it is apt that we celebrate the birth of its greatest romancer, the presiding deity of Urdu poetry, Khuda-e-Sukhan (God of poetry), Mir Taqi Mir who was born in Agra (then ‘Akbarabad’) in this very month in 1722. His autobiography, Zikr-e-Mir, does not give his date of birth but some manuscripts found in the personal library of the Raja of Mahmudabad establish it with reasonable certainty.

Mir arrived in Delhi in or around 1733 and made the city his home. It is believed that in Delhi Mir lived at three different addresses — Kucha Chelan, Chandni Mahal and Matia Mahal – all in the heart of the walled city. He stayed in Delhi till 1782 and, during this long period of his stay in Delhi, he remained under the patronage of one or the other nobleman.

He was patronised, one after the other, by Itimad-ud-Daula II, Javed Khan, Raja Nagar Mahal, Imad-ul-Mulk, Raja Jugal Kishore and Raja Nagar Mal. With most of them he broke ties on issues of self-respect and principles – matters on which he never compromised, even mildly. In matters of self-respect he was so sensitive that, more often than not, people labeled him as arrogant. In matters of principles, he was dismissed as haughty. He was aware, and rightly so, of the superiority of his work as against the works of most of his contemporaries and insisted that, on merit, he was entitled to a much more exalted stature and status than them.

Eighteenth century Delhi had its own Bassis and Iranis. With one royal invasion after the other – the last being of Ahmad Shah Abdali – Delhi was reduced to ruins. Mir could not bear his beloved city being blatantly ravished and eventually went into seclusion. The only way out of this misery, it seemed, was migration to Lucknow where the ruling Nawab, Asaf-ud-Daula, was known for his love for Urdu poetry and patronage for Urdu poets.

Finally, in 1782, with a heavy heart and tearful eyes, Mir bid adieu to Delhi for good and migrated to Lucknow where he was received by the Nawab in person. Though he lived in Lucknow till his end, the distance from Delhi always hounded him. For Mir, Delhi’s lanes were no less than an artist’s painting :

Jo shakl nazar aayi, tasveer nazar aayi

These are not Delhi by-lanes, these are artist’s canvas

Every sight I see looks like a painting

However, he was distraught at the thought that the city and its people were being incessantly plundered and pillaged by one or the other invader. Narrating the plight of the citizens of this frequently ransacked city, he lamented :

Chaiyn mein hain jo kuchh nahin rakhtey, fiqr hi ek daulat hai ab

Thieves, pickpockets, Sikhs, Marathas, affluent and indigent – all are in need

In peace are those who do not possess anything, poverty itself is wealth

and

Deeda-e-giryaan hamaara neher hai

Dil-e-kharaaba jaise Dilli sheher hai

My weeping eyes are like a canal

My ruined heart like the city of Delhi

Accounts of his arrival in Lucknow also reveal his profound and rather passionate feelings for Delhi. It is said that the day he arrived in Lucknow, there was a mushaira he had to attend. New to the city of the flamboyant Nawabs, he reached the elitist gathering alone in an old-fashioned and modest dress. Being out of style and not in vogue he was easily noticed, but was not recognized until he came up with one of his most famous and now oft-quoted verses :

Hum ko ghareeb jaan ke, hans hans pukaar ke

Dilli jo ek sheher tha, aalam mein intekhaab

Rehte thay muntakhab hi jahaan rozgaar ke

Us ko falak ne loot ke veeraan kar diya

Hum rehne waale hain usi ujde dayaar ke

What whereabouts do you ask of me, O people of the East ?

Considering me an alien and laughing at me

Delhi, that was a city unique on the globe

Where lived only the chosen of the time

Destiny has looted it and made it deserted

I belong to that very wrecked city

Discovering who he was, the highbrowed attendees embraced him and Mir made Lucknow his home for his remaining life. Though he spent almost 28 years in Lucknow, he never forgot Delhi and would often compare it favourably to Lucknow.

18th Century Delhi had its own Bassis and Iranis. With one royal invasion after the other – the last being of Ahmad Shah Abdali – Delhi was reduced to ruins. Mir could not bear his beloved city being blatantly ravished and eventually went into seclusion.

Russell reports that once some leading noblemen of Lucknow called upon Mir and, after exchanging pleasantries, requested him to recite for them. Initially Mir was evasive but when the gentlemen insisted, he clearly told them that they would not understand his poetry, on which one of them remarked :

“But we understand the poetry of Anvari and Khaqani – the greatest of Persian poets”.

Mir immediately retorted :

“I am sure you do. But to understand my poetry what you need to know is the language that is spoken at the steps of the Jama Masjid of Delhi and that knowledge you do not have”.

Mir soon had a fall out with Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula too. Once again, it was Mir’s lack of tolerance for what he considered discourteous behaviour on part of the Nawab that made him part ways with his benefactor. The Nawab, however, did not stop paying Mir his stipend. His successor, Nawab Sa’adat Ali Khan continued the tradition but Mir cared two hoots for him too, to the extent that once he even refused to accept robes and money sent to him by the Nawab, asking the messenger to advise the Nawab to give it away in charity :

Kal us pe yahin shor hai phir nauhagari ka

The head that today takes pride in wearing the crown

Tomorrow there are cries of mourning here on the same

Eventually, the Nawab – acting like a present-day university administration, stopped Mir’s stipend and Mir fell into penury. He started growing antagonistic towards Lucknow and regretting his decision to leave Delhi :

Vahin maiyn kaash mar jaata, sara seema na aata yahaan

The deserted Delhi was far better than Lucknow

Wish I had died there itself and had not come running here

Mir was a poet of love and romance. He lived in an age when Urdu poetry was still in its infancy. In his Ghazals he created an inimitable language and style of his own :

Jaane na jaane, gul hi na jaane, baagh toh saara jaane hai

Chaaragari beemari-e-dil ki rasm-e-shehr-e-husn nahin

Varna dilbar-e-naadaan bhi, is dard ka chaara jaane hai

Mehr-o-wafa-o-lutf-o-inaayat, ek se waaqif in mein nahin

Aur to sab kuchh tanz-o-kanaaya, ramz-o-ishaara jaane hai

Every leaf and every bud knows my state

Only the flower doesn’t know, rest of the garden does

Curing the affliction of heart is not the tradition of the city of beauty

Else even the naïve beloved knows the cure to this pain

Mercy, loyalty, kindness and favour – none of them are aware of

All that they know are taunts and gestures, signs and allusions

Mir’s poetry is a poetry of unfulfilled love; it is a poetry of yearning, of desire and of craving:

Hamein aap se bhi juda kar chaley

Jo tujh bin na jeene ko kehte thay hum

So iss ahd ko ab wafa kar chaley

Bohot aarzoo thi gali ki teri

So yaa’n se lahu mein naha kar chaley

Jabee’n sajda kartey hi kartey karte gayi

haq-e-bandagi hum ada kar chaley

Parastish ki yaa’n tak ki aye buth tujhe

Nazar mein sabo’n ki, khuda kar chaley

She so appeared that I forgot myself

She separated me from myself

My claim of not living with you

That pledge I am now honouring

I aspired a lot to reach near you

From here then I returned soaked in blood

The head kept bowing down in prostration

The duty of servitude I discharged

I worshipped you to such an extent that, O idol !

Made you God in the sight of all

On the one hand, the poet was enthralled by his beloved’s beauty :

Pankhari ek gulaab ki si hai

Mir in neem-baaz aankhon mein

Saari masti sharaab ki si hai

What to say of the tenderness of her lips

It’s like the petal of a rose

O Mir ! in these half-closed eyes

Wine-like intoxication is writ large

And on the other, he grumbled that falling in love was a headache :

Jaan ka rog hai, bala hai ishq

Ishq hi ishq hai jahaan dekho

Saare aalam mein bhar raha hai ishq

Ishq maashooq, ishq aashiq hai

Yaani apna hi mubtala hai ishq

Mir ji zard hotey jaate hain

Kya kahin tum ne bhi kiya hai ishq ?

How should I tell you what love is ?

It’s a sickness of the soul, it’s a curse, this love

There is love and just love wherever you look

The world is overflowing with love

Love is the beloved, love is the lover

As if love is involved in itself

This Mir fellow is becoming pale

Have you also fallen in love ?

Despite being the son of a religious scholar, Mir – like Ghalib – did not hesitate in audaciously announcing his incredulity to religion and religious formalism :

Dekha is beemaari-e-dil ne, aakhir kaam tamaam kiya

Kis ka Kaaba ? kaisa qibla ? kaun Haram hai ? kya ehraam ?

Koochey ke us ke baashindon ne, sab ko yahin se salaam kiya

Sheikh jo hai masjid mein nanga, raat ko tha maikhaane mein

Jubba, khurqa, kurta, topi, masti mein inaam kiya

Mir ke deen-o-mazhab ko ab poochhte kya ho, un ne toh

Qashqa kheincha, daiyr mein baitha, kab ka tark Islam kiya

All my efforts went in vain, the medicine didn’t work at all

Did you see, this heart disease at last killed me

Whose Ka’aba ? what prayer-direction ? what Holy mosque ? what pilgrim’s robes ?

We, the inhabitants of her lane, abandoned all from here

The Sheikh who stands naked in the mosque today, was in the pub last night

Cloak, gown, shirt, cap – in inebriation he gave away as tips

What do you now want to know about Mir’s religion and faith, he in fact has

Tattooed the forehead, sat in the temple, abandoned Islam long ago

Mir was a man of traditional values. He was aghast at the changing values of his times in Lucknow. He could not bear the thought that he was living amongst people who were oblivious to old principles, traditions and values which were quintessential to his very existence. Mir’s repulsion to such social transformation became more intense with time and reverberates in his later poetry:

Kya log zameen par hain, kaisa ye samaa’n aaya ?

Once the tradition of decency disappeared from the world

What kind of people are there on earth, what scenario is this ?

Kya zamaana tha vo jo guzra Mir

Hamdigar log chaah karte thay

What an age was it that has gone by, Mir

People used to love each other

Mir is the first Urdu poet whose complete works were typeset and printed. The voluminous “Koolliyati Meer Tyqee” [should be spelt as Kulliyaat-e-Mir Taqi / ‘Complete works of Mir Taqi’] was published in 1811 as a major literary project sponsored by the Fort William College in Calcutta.

Mir’s Urdu poetry is spread over six diwans. Till his fifth diwan, composed in an advanced age, his ghazals make it clear that Mir hoped to find refuge in a more cultured and agreeable place than Lucknow. The city seemed gloomy to him and he found it “hard for a man to live (t)here any longer”. By the time the last diwan was penned, the sourness receded. Not because his views on the city changed but because he had no more strength to criticize. He had already lost his wife, daughter and son. His friends were dying one by one. He was penniless and seriously ill with a painful gastrointestinal disease. Despite these hardships, he continued to write and recite :

Gaah-o-begah, ghazal saraayi hai

I have no other work to occupy me now

In and out of season, I recite my poetry

On September 21, 1810, Mir died in Lucknow at the age of 88. He was buried in the graveyard of Bheem Ka Akhaara located north of what is today called the City Station. Until half a century ago, a grave situated just before the Chhatte Waala Pul near the City Station railway tracks was believed to be that of Mir.

Today, there stands a humungous slum on the spot where the grave once existed and where Mir spent the last three decades of his life. There is no sign either of his house or of his grave. Few years ago, I walked all over the area for hours enquiring about the remnants and relics of the poet’s life (or death). There was hardly a soul in the vicinity who had even heard of the poet, let alone knowing about his remnants. An old resident of the area, one Baqai saheb, who runs a printing press right in front of the spot where Mir’s grave is said to have once existed, was kind enough to treat us to a hot cup of tea and tell us that the area had been usurped by land-grabbers long ago.

A lone broken stone erected in a park calls itself the ‘Nishaan-e-Mir’ and, if someone can search for it, an almost invisible and decrepit road-sign at the end of the street reads ‘Mir Taqi Mir Marg’. These are the only tangible signs of this Khuda-e-Sukhan (God of Poetry) that exist in Lucknow today.

It seems that Mir had commanded the powers that be to make it clear to future generations that he would not want those admirers to visit his grave, who didn’t care for him when he was alive :

Yaad aayi merey Eesa ko dawa merey baad

O Mir, he came to my grave after I died

My Messiah remembered my cure after I had gone

After my return from Lucknow, with my friends, Kanishka Prasad and Akila Jayaraman, I also trotted the Walled City with the help of a veteran Purani Dilli photographer. The experience was even more painful than that in Lucknow.

Residents of Kucha Chelan, Chandni Mahal and Matia Mahal – neighbourhoods which Mir had once described as “artist’s canvas” and whose by-lanes once echoed with his poetry, do not even know who Mir was, much less where he lived. My recitation of Mir’s well-known couplet which aptly describes this harrowing state of affairs in Mir’s Delhi was also lost on them :

Kya imaarat ghamon ne dhaayi hai

My heart’s siege is quite a sight

What a castle have sorrows razed ?

And, why should it not have. After all, Mir had himself prophesised :

Baatein hamaari yaad rahein, phir baatein aisi na suniye ga

Parhtey kisi ko suniye ga, toh der talak sar dhuniye ga

Remember my words for you will not hear such words again

If you hear someone narrating them, you will bang your head in wonder