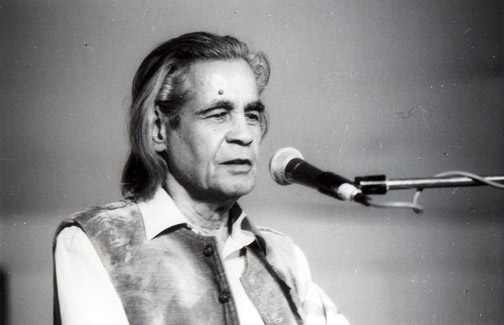

Courtesy: sahmat.org

The October 2000 edition of Seminar contains an obituary penned by Irfan Ahmad for the renowned Urdu poet, Ali Sardar Jafri, whose 102nd birth anniversary we celebrated on the 29th of November this year, just a week before the 23rd anniversary of what has been the most bald-faced blow to our Constitutional democracy so far. The obituary opens with these words :“It would be violative of the ideals and convictions of Ali Sardar Jafri to write his obituary” and goes on to explain that the poet believed that he would “eternally live in the sweet song of birds and the musical smile of dry leaves” and that, much like Ghalib, “one day all the golden rivers and blue lakes in the sky would reverberate with the music of his being”. While the author of the obituary was obviously alluding to the romantic poetry of Ali Sardar Jafri, it is actually his poetry in defence of secularism, combating communalism and dreaming of an equal and just world,that makes him immortal.

Exactly 23 years ago when a methodical and planned movement devised to massacre our Constitutional ideals of secularism, justice, liberty, equality and fraternity in the name of religion was at its peak, the 79-year old communist poet decided to address God and tell him how his name was being misused to create ruckus :

Hai dharm siyaasat ke madaari ka khilauna

Mazhab ko bana rakhkha hai yaaron ne kharabaat

Japtey hain tere dhyaan mein jab Ram ki maala

Kuchh aur bigad jaate hain is des ke haalaat

Insaa’n ko bana dete hain insaan ka dushman

Jab Hind ki taareekh pe likhte hain maqaalaat

De saktey nahin naan ka sookha hua tukda

Utthey hain chukaane ko jo barson ke hisaabaat

Faith is a toy in the hands of the political puppeteer

These blokes have made mischief out of religion

When they roll a rosary chanting your name

The situation in this country becomes worse

They make men enemies of each other

When they write commentaries on the history of India

Those who can’t give even a dry piece of bread

Have sworn to settle accounts for years

And when the massacre was successful and led to people killing each other on the streets, he wondered if this land of Ram and Buddha, the sentinel of human dignity, will be rendered barren and promised to donate to his country, whatever blood was left in his body after the on-going riots :

Ram-o-Gautam ki zamee’n, hurmat-e-insaa’n ki amee’n

Baanjh ho jaayegi kya khoon ki barsaat ke baad ?

Ae vatan, Khaak-e-vatan, vo bhi tujhe de deinge

Bach gaya jo bhi lahu, ab ke fasaadaat ke baad

This land of Ram and Gautam, the sentinel of human dignity

Will it be rendered barren after it rains blood this time ?

Oh Nation, dust of my Nation, we will render unto you

Even the blood that is left in us after the on-going riots

Ali Sardar Jafri was a radical activist and a true chronicler not only of the events that surrounded him, but of his inner moods, feelings, and susceptibilities. Like Frances Pritchett says about Mir, his verse is felt, even by an unsympathetic critic, as ‘moving and powerful’, a kind of poetry which ‘at its best, comes from the heart and goes to the heart’. He wrote extensively on a variety of subjects, produced insightful documentaries, recited with overwhelming intensity and spoke with great erudition – the underlying theme in whatever he did always being love, compassion, justice and fraternity. He abhorred communalism, detested fanaticism, fought bigotry and intolerance and sought to protect the highest traditions of religious pluralism and social diversity.

Born on 29th November 1913 in an aristocratic family of the backward Balrampur district, now in Eastern UP, a young Jafri soon saw the darkness that India was plunged into and decided to join politics and write at the same time. He began his career at 17 as a short story writer. His very first collection of short stories, ‘Manzil’ (destination) was considered both seditious and libellous by the ruling British and he had to serve eight months in prison for denouncing the idea of war :

Zeheraalood vo beete hue lamhaat ke dank

Khoon mein doobi hui vo subh ki talwaar ki dhaar

Shaam ki aankh mein baarood ke kaajal ki lakeer

Aur hafton ke sipaahi vo maheenon ke sawaar

Jo mere josh-e-baghaawat ko kuchalne ke liye

Faujdar fauj kiya karte hain yalghaar apni

Rifle karti hai faulaad ke hothon se kalaam

These poisonous stings of the moments that have passed

That blood-soaked edge of the morning’s sword

In the evening’s eye that kohl line made of gunpowder

And those soldiers marching for weeks and riders for months

Who, to crush the passion of my rebellion

Continue to attack, army after army

The rifle salutes the lips of steel

Not to be deterred, he continued to write. He published his first collection of poetry ‘Parwaaz’ in 1943 and, soon after Independence, in 1948 wrote his magnum opus ‘Nayi Duniya ko salaam’ – a long poem brimming with hope and sanguinity. Jafri’s dissent was not aimed at state action alone. He attacked social malpractices with equal gusto. In ‘Awadh ki khaak-e-haseen’ he picturesquely describes the social conditions of the downtrodden in the Oudh province ruled by capitalist landlords :

Ghareeb Sita ke ghar pe kab tak rahegi Ravan ki hukmraani ?

Draupadi ka libaas uske badan se kab tak chhina karega ?

Shakuntala kab tak andhi taqdeer ke bhanwar mein phansi rahegi ?

Yeh Lakhnau ki shaguftagi maqbaron mein kabtak dabi rahegi ?

How long will poor Sita’s home continue to be ruled by Ravana ?

How long will Draupadi’s clothes be snatched from her body ?

How long will Shakuntala remain caught in the swirl of blind fate ?

How long will this blossom of Lucknow remain buried under tombs?

One of the most robust pillars of the Progressive Writers’ Movement, Jafri did not confine his poetry to the trials and tribulations of the people of India alone. He spoke for the African girl (Afreeki Ladki), lent words to the torment of an Abyssinian boy (Habshi mera bhai) and paid tributes to Pablo Neruda, Elia Ehrenberg and Nazim Hikmet.

Jafri genuinely believed in the idea of Indo-Pak peace and friendship. When Pakistani poet Ahmad Faraz extended a hand of friendship to his Indian friends in his oft-quoted words :

tumhaare des mein aaya hoon dosto, ab ke

na saaz o naghma ki mehfil, na shaayri ke liye

agar tumhaari ana ka hi hai sawaal to phir

chalo, maiyn haath barhaata hoon dosti ke liye

I have come to your country, friends, this time

Neither for a get-together of melody and song nor for poetry

If it’s only a question of your ego, then

Here, I extend my hand in friendship

Jafri responded with equal eloquence and camaraderie :

Zameen-e-Pak hamaare jigar ka tukda hai

Hamein hai azeez Dilli-o-Lucknow ki tarah

Tumhaare lehje mein, meri nawa ka lehja hai

Tumhaara dil hai hasee’n, meri aarzoo ki tarah

Karein ye ahd, ke auzaar-e-jang hain jitne

Unhein mitaana hai aur khaak mein milaana hai

Karein ye ahd, ke arbaab-e-janghain jitney

Unhe sharaafat o insaaniyat sikhaana hai

Tum aao gulshan-e-Lahore se chaman bardosh

Hum aaein subh-e-Banaras ki roshni le kar

Himalaya ki hawaaon ki taazgi le kar

Phir is ke baad ye poochhein ki ‘kaun dushman hai’

Pakistan is a part of our heart

It is as dear to us as Delhi and Lucknow

In your accent is the inflection of my speech

Your heart too is beautiful like my desire

Let us pledge that all these instruments of war

Have to be destroyed and buried in dust

Let us pledge that all these masters of war

Have to be taught lessons in civility and humanity

You come from the garden of Lahore, carrying flowers

We come, carrying the light of the morning of Banaras

The freshness of the breeze of the Himalayas

And after that, ask “who is the enemy” ?

Jafri had a deep interest in classical poetry in both Urdu and English and himself edited anthologies of Kabir, Mir, Ghalib and Meera Bai with his own scholarly introductions. He wrote plays for the Indian People's Theatre Association (IPTA), produced a documentary film titled ‘Kabir, Iqbal and Freedom’ and the well-known 18-part television serial ‘Kahkashan’ based on the lives and works of seven progressive Urdu poets of the 20th century who he had known personally.

As we celebrate the birth anniversary of this defender of our pluralistic and egalitarian traditions, let us hope, in his words, that forces of communalism and intolerance do not rip apart the democratic fibre of this country and dialogue never ceases :

Guftgu bandd na ho, baat se baat chaley

subh tak shaam-e-mulaaqaat chaley

hum pe hansti hui ye taaron bhari raat chaley

subh tak dhal ke koi harf-e-wafa aayega

ishq aayega ba-sad laghzish-e-pa aayegaa

nazrein jhuk jaayeingi, dil dhadkeingey, lab kaanpeingey

khamoshi bosa-e-lau ban ke behek jaayegi

sirf ghunchon ke chatakney ki sada aayegi

aur phir harf-o-nawa ki na zaroorat hogi

chashm-o-abroo ke ishaaron mein mohabbat hogi

nafrat uth jaayegi, mehmaan murawwat hogi

haath mein haath liye, saara jahaan saath liye

pyaar ki sau ghaat liye

regzaaron se adaawat ke guzar jaaeingey

khoon ke dariya se hum paar utar jaayein

guftgu bandd na ho, baat se baat chaley

Let dialogue never cease, let talks lead to talks

Till the morning let the evening of our meeting last

Laughing on us, let this star-filled night last

By morning, some word of loyalty, fully moulded, will arrive

Love will arrive, though with trembling feet, it will arrive

Eyes will lower themselves, hearts will beat and lips shiver

Silence will go astray, having turned into a kiss of flame

Only the sound of cracking of the buds will be heard

And then words and voice won't be required any longer

In the signs of eyes and eyebrows will love linger

Hatred will vanish, kindness will be our guest

Holding hand in hand, taking the whole world with us

Holding the gift of love

We will traverse the deserts of enmity and cross over the river of blood

Let dialogue never cease.