Attitudinal violence and structural violence contribute immensely to physical violence in the forms of communal riots and mob lynching. This was the scenario facing India in 2019. There were 25 incidents of communal riots in India in 2019, and 108 incidents of mob lynching, according to the monitoring of Centre for Study of Society and Secularism (CSSS). CSSS monitors reportage of communal riots and mob lynching in the Mumbai editions of five leading newspapers- The Indian Express, The Hindu, Times of India, Inquilab and Sahafat. As per the reportage in these newspapers, the number of communal riots in 2019 (25) is lesser than 2018 where 38 communal riots were reported in the same newspapers.

Though the number of communal riots has declined, the discourse of communal violence driven by ideology of Hindutva supremacy remains the same. Newer issues are being used to heighten the discourse of communal violence- for instance the discriminatory legislation of Citizenship Amendment Bill which excludes Muslims linked with NRC, the abrogation of article 370 in Kashmir and the clamp down on communication subsequently, the demand for construction of Ram Temple in Ayodhya. Thus, though it appears that the number of communal riots has declined, that in no way can be construed as decline in communal discourse leading to communal violence itself. If at all, through discriminatory legislations and increasing dismantling of democratic institutions which were expected to safeguard democracy, communal violence is taking deeper roots in our society. The discourse promoted by the ruling party in conjunction with the impunity and patronage given to police and non state cadre is effectively perpetrating violence against the marginalized. Even if the number of communal riots is low, communal violence has stronger manifestations in structural and attitudinal violence.

Methodology of Monitoring:

The findings of Centre for Study of Society and Secularism (CSSS) are based on the reportage of communal riots reported in Mumbai editions of five newspapers- The Indian Express, The Times of India, The Hindu, Sahafat and Inquilab. This is also the limitation of the findings since they are based on the city editions of only these five newspapers. In the past, CSSS could give a fair comparison between the number of communal riots emerging from its monitoring and the number of communal riots reported by the National Crimes Report Bureau (NCRB) which used to routinely place this data in the public domain. It’s interesting to note that though the Minister of State for Home Affairs G Kishan Reddy claimed that the Centre has zero tolerance for incidents of communal violence, it hasn’t proved this claim through figures and stopped giving out data(Scroll in, 2019). The NCRB ceasing to publish data of the communal riots from 2017 is no mere coincidence. In the past, the number of communal riots reported by the NCRB or the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) was way higher than that reported by CSSS.

Sections: Communal riots and Mob Lynching

As explained last year in its report, CSSS reported that though there is a decline in the number of communal riots in India in 2018, it doesn’t imply that there is a decline in communal violence (Engineer, Dabhade, Nair, & Pendke, 2019). Communal violence is a broader term encompassing communal riots as well as mob lynching. While the number of communal riots is declining according to the reportage in the Mumbai edition of these five newspapers, the number of mob lynching is increasing. Mob lynching is an instrument to achieve the objective of sustained communal polarization by involving communal symbols like cow, the issue of love jihad or even the more innocuous pretexts like theft etc targeting the Muslims. In 2019 too, the same pattern continued where though the number of communal riots decreased, the number of mob lynching were high. Thus the report of communal violence which manifested itself in the form of physical violence is divided into two sections: Communal riots and Mob lynching.

This section will attempt to understand the salient features of communal riots in 2019.

Salient points:

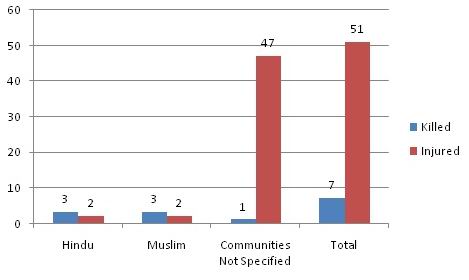

Religion wise break up of deaths and injuries:

In 2019, from January 1 to December 31, according to the above mentioned newspapers, 25 communal riots took place in 2019. In these 25 riots, 8 lives were claimed. Out of the 8 persons deceased, three killed were Hindus, three killed were Muslims and the communities of two persons killed were not specified in the reports. The two Hindus were killed in Maharashtra and UP. In the communal riot in Maharashtra, a fight broke out between the two groups which got a communal angle. The fight broke out during a game of gambling in the Amravati resulting in the death of one Sham Phelwan. A riot ensued and subsequently two Muslims were killed in the riots. In the Muzzafarnagar district of Uttar Pradesh, again, a personal conflict over a trivial issue of kite flying between some children assumed the communal colour. Both sides confronted each other and one group entered the house of the deceased, Raj Kumar and attacked him and other family members. Raj Kumar got critically injured in the clash and later died while being taken to hospital. One Vishnu Yadav died after being attacked over the issue of stone pelting during a procession of immersion of some idols in Bihar’s district of Jehanabad. One more Muslim, Jamiruddin Tapadar died in Hailakandi, Assam. This riot was resulting from a traffic congestion caused due to Friday prayers. 54 persons were injured in these 25 incidents of communal riots.

Graph 1: Religion wise break up of deaths and injuries:

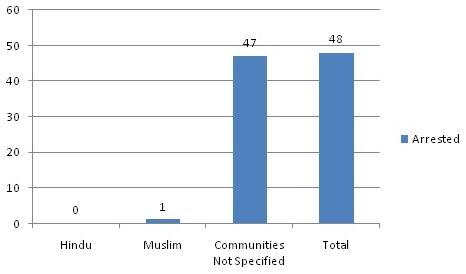

Religion wise break up of Arrests:

In 25 incidents of communal riots, there were a total of 48 arrests. 47 of the arrested from 48 arrests were from unspecified community whereas one was a Muslim. There were no arrests of specifically any Hindu.

Graph 2: Religion wise break up of Arrests:

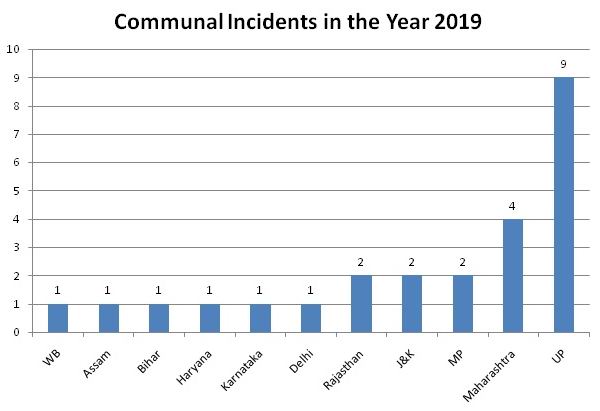

Region wise break up of communal riots:

The state of Uttar Pradesh continued to top the list of states which had the most number of communal riots. Out of 25 communal riots, 9 took place in UP. This is contrary to the claim of the Chief Minister of UP who claimed that there have been no communal riots in UP after BJP came to rule (Times of India, 2019). UP was followed by the state of Maharashtra where 4 communal riots were reported in 2019. Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Jammu and Kashmir each had two communal riots in 2019. In the states of Karnataka, Haryana, Assam, Delhi, Bihar and West Bengal reported one communal riot each.

These figures indicate that communal riots have mostly been reported in the northern zone of the country and the north has been the theatre of violence with deep faultlines. The western zone of the country has been prone to communal violence traditionally. Interestingly, though no communal riots from Gujarat were reported in the Mumbai editions of the five newspapers, the local newspapers in Gujarat have reported 9 incidents of communal riots in 2019.

However it will be misleading to believe that there is little or no menace of communal violence in the South and Eastern parts of the country only because of the low number of communal riots reported from these regions. The communal discourse replete with hatred and hate speeches is very much prevalent in the east and south. The discourse is infused with newer issues like Citizenship Amendment Bill, National Register of Citizens, abrogation of article 370 in Kashmir and the overall narrative of Muslims being disloyal and second class citizens of India. Such a discourse manifesting in structural and attitudinal violence has sharply polarized the communities along religious lines.

Graph 3: Region wise break up of communal riots:

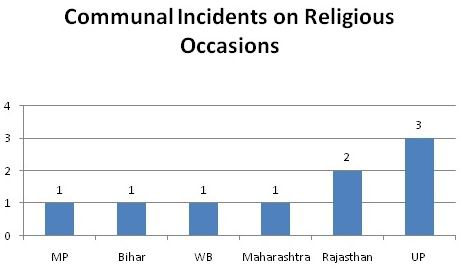

Triggers/ Immediate causes:

In total, nine incidents of communal riots are associated with religious processions, festivals or celebrations. As observed in the previous few years, aggressive sloganeering, deliberate loud music to instigate the other communities, deliberating planning procession routes to clash with other religious communities has been used as a pretext to trigger communal riots. Out of the – riots, four took place in the state of UP, two in Rajasthan, one in Maharashtra, one in Madhya Pradesh and one each in West Bengal and Bihar.

Graph 4: Triggers/ Immediate causes:

In 2019 too like in 2018, the use of religious processions and festivals has been instrumental in fomenting communal tensions leading to violence. Out of the 25 communal riots, nine were triggered off by or during religious processions. The Kanwariyas or the Kavadyatras have been given protection and state patronage in a way that the State has favoured them. Out of the nine communal riots triggered due to issues related to religious procession, three took place in UP itself. In the Badaun district of UP, stone pelting took place during a Kanwariya yatra which coincided with the timings of Id namaz. The Muslims objected to the loud religious music played in the yatra which led to the riot. In Agra, members of Bajrang Dal protested against the Muslims offering the Id namaz on the road. 70 Bajrang Dal members who were not allowed to pass through the road due to the prayers threatened to recite Hanuman Chalisa on the road. In Balrampur district of UP, stone pelting took place during the idol immersion ritual on Dussera over playing of music.

In 2019, in Hingoli district of Maharashtra, the participants in the Kavad Yatra came in conflict with a group of Muslims who were together to offer Eid prayers. The procession had devotional songs playing on speakers. Both the groups started shouting religious slogans. In Jaipur, Rajasthan, communal riot ensued after a Haridwar bound bus was pelted by stones by some Muslims and blocked the Delhi Highway. This was a fall out of the tensions with the Kanwariyas. In Tonk district of Rajasthan, stones were pelted at a Vijayadashmi procession in the town, triggering vandalism and arson. Locals staged a sit-in outside the Malpura police station and refused to burn the effigies of Ravan till their demand for immediate arrest of the miscreants was met.

In Shajapur in Madhya Pradesh, stones were pelted on a Muharram procession. During the violence some two wheelers were set on fire. In Jehanabad, Bihar, riot broke out when a stone was thrown at the procession being taken out for immersion of idols near the Arwal More. The devotees blamed by-standers belonging to another community for the same after which both sides indulged in heavy stone-pelting which had left 14 people injured. The riot claimed two lives. Several shops in the area were set on fire by the rampaging mobs and the situation was brought under control after prohibitory orders were issued.In Purba Medinipur in the state of West Bengal, Christmas celebrations in a Church were disrupted when a group of men entered the church premises raised slogans “Jai Shree Ram”, attacked about 100 worshippers and vandalised the church and a vehicle belonging to the pastor. According to police, one was severely injured and others few had minor injuries and the locals appeared to be associated with the BJP as per the initial investigation.

Though religious festivals or processions remain the main reason emerging from the reportage of communal riots, there are other triggers that have led to communal riots which are insightful as far as understanding the patterns of communal riots are concerned. Rumours of cow slaughter/ beef and eve-teasing of women by members of “other” communities are still triggers for communal riots. However there is a more overt and aggressively emboldening shift in the pattern where Muslims are targeted and attacked and told to go to Pakistan, sending a message that they are second class citizens of the country and don’t belong to India. In a blatantly shocking incident in Dhamaspur in Gurgaon, members of a Muslim family and guests who had come to visit them were beaten with sticks and rods, allegedly by 20-25 men, who barged into their home and attacked them on Holi evening. The incident took place when some of the accused allegedly approached the boys from the family, who were playing cricket outside, and demanded that they “go to Pakistan and play”. During the attack the family members were beaten up mercilessly and their house was damaged along with 2 motorbikes and a car. The accused also fled with valuables from the house. This is not an isolated incident but comes in the wake of the persistent attacks on individuals across the country demanding them to chant “Jai Shri Ram” or asking Muslims to go to Pakistan, especially after the re-election of BJP in general elections.

Role of the State:

The State in its response to communal riots is guided by its ideology of Hindutva or supremacism based on religion. Muslims and other minorities are targeted by state and non- state taking cue from the hate speeches of those in power and the active network of patronage. This has allowed the violent supremacist to wreck violence with impunity. The police did not only fail to prevent the riots or bring the culprits to justice, but the police itself have indulged in violence against the innocent. The response of the police at Jamia in the midst of protests against the discriminatory CAA was starkly telling of this pattern. In unprecedented action, the police entered the Jamia Milia Islamia campus in Delhi on 15th December, 2019 and beat up the students with batons and used tear gas. The police have reportedly used stun guns used in terrorists operations to attack students of Jamia in their hostels and libraries leading to one student losing one of his eyes and other one losing one arm. The police action at Seelampur was also condemnable. One can’t help but notice that the police have become a brute force or army of the ruling party and wrecks violence on innocent students and Muslims whenever ordered to do so with no regard to law and order. The police indulge in shoddy investigation to allow the culprits to exploit the loopholes and go scot free.

The judiciary too has been tardy and not hearing these cases with priority, thereby delaying and now clearly denying justice. The role of the executive and the police in Uttar Pradesh has been particularly disturbing given how it has violently targeted the Muslim community leading to 23 deaths, and recovering the cost of damage from the Muslim community with a vengeance to break the very morale and backbone of the protest against the CAA.

Instead of acting as an antidote to hatred and violence, the State has actually turned against its own citizens and is attacking them in the most brutal. The State has become so overbearing that it has influenced all arenas of public knowledge and debates like it has in terms of state institutions. The media especially is influenced to only present the narrative weaved by the state and achieving this with whatever means necessary- manipulation of facts and highly partial coverage of news. Such incredibly biased reportage is shaping the popular imagination of the country and shrinking the spaces for impartial and objective public debates.

Conclusion:

2019 sees the brazen communal attitude of the State which is using all its organs to maintain a highly polarizing communal discourse. This discourse doesn’t depend on communal riots alone but has in fact found many other forms to seep into the Indian society. However, the year 2019 ended with re-invigorating energy and hope when citizens across religious identities came together to put up a determined and spirited protests to save the constitution of the country in the face of discriminatory laws pushed by this government matched only by its brutality to defend these laws. Such unity may be the anti-dote required to counter communal riots.