Image Courtesy:mhi.org.in

Image Courtesy:mhi.org.in

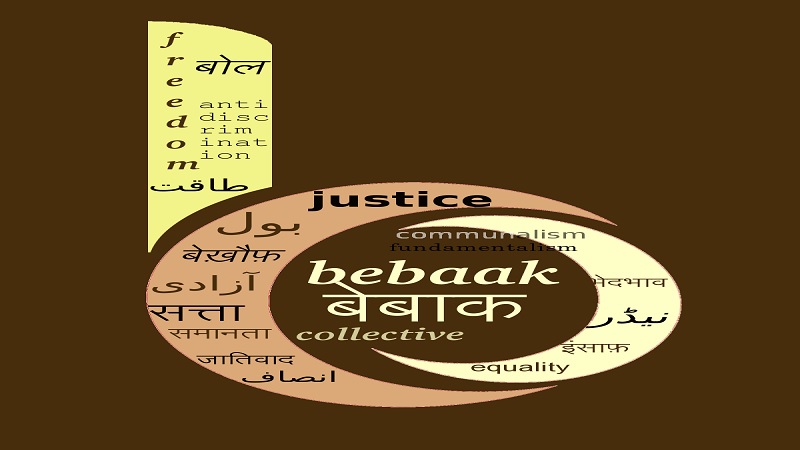

The Bebaak Collective, an umbrella body of several women’s groups published the ‘Communalisation of Covid-19: Experiences from the Frontline’ report on January 21, 2021 during a virtual conference to highlight the rampant communalisation during the coronavirus lockdown.

The report, covering seven states from northern, central and western India, documents the discrimination and violence faced by Muslims due to communalisation of the pandemic. Authors Hasina Khan, Khawla Zainab and Umara Zainab interviewed various civil society organisations, student activists, human rights lawyers, other individuals and citizen groups working on the frontlines, and used media reportage to reveal the pattern of anti-Muslim violence during the pandemic.

Moreover, the report recommended measures such as:

- an effective overseer over media that fail to follow journalistic ethics

- intervention of the Press Council of India and NBSA

- introduction of a religion-based anti-discrimination law similar to the SC/ST Prevention of Atrocities Act

- mental health support to Muslims who faced widespread stigma, hatred and discrimination

- implementation of the Sachar committee recommendations especially the Equal Opportunity Commission and Diversity Index

- Supreme Court cognisance of this gross hate propaganda.

In response, renowned journalist, activist and SabrangIndia co-founder Teesta Setalvad congratulated the Collective for taking up the initiative. She reminded the audience that the grievances suffered by Muslims, migrant workers, adivasis and other marginalised communities were the result of growing schisms in society that amplified institutional failures.

Further, she said, “We respond to moments of crisis rather than continuums of crisis. We need to seriously think about institutional lacunae and the short memory of the administration that fails to deliver its services.”

Setalvad warned that the dangers of amplification have become much more severe in times of social media. But still these “agents” did not work before. She said that the growing misinformation and manipulation of history demands a better understanding of historical events to solidify future actions, especially in the case of young activists.

Accordingly, she referenced interviews of Arundhati Roy that talked about communalisation of the pandemic and similar documentaries for a more comprehensive perspective.

Regarding Muslim ghettoisation, she said that real estate prices have soared to keep Muslims from affording houses in specific neighbourhood. However, less mixed neighbourhoods endanger all conversations from all perspectives.

“When we get limited to silos then these problems get much worse,” she said.

Taking this idea of silos a step ahead, Setalvad talked about the Wall Street journal article that talked about the giant corporate allying with powerful governments. Such partnership restricts communication between differing groups, meaning that Facebook algorithms circulate the same message in the same group.

Referring to the Global Dissemination report by Oxford, the activist said that Facebook and other social media platforms give us a false assurance that they are open. As such she recommended that the Collective’s report include a need for supporting independent media platforms.

“How do alternate media platforms function without the support of such groups? Without that support you cannot expect voices to carry on further,” she said.

Referring to Bebaak’s report, Setalvad said that while the report talks about High Court verdicts favouring minorities, it also needs to consider speaking order.

She told the audience that 205 FIRs were filed against 2,765 foreign nationals in 11 states of the country as reported by SabrangIndia. Yet every single one of these foreign nationals was exonerated.

Setalvad argued that the most important verdict was that of the Nagpur bench on August 21, 2020 that pulled up police and media for the actions against the community. She emphasised that unless the order is speaking, there is very limited relief, and pointed out that there was a lack of judicial action against hate speech.

“Nowhere do you have constitutional courts actually questioning the dangers of hate speech. I ask you all to visit Citizens for Justice and Peace website that shows five dozen complaints against the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting against digital and institutional platforms. We need to understand the relation between hate and media,” said Setalvad.

She referred to the growing hate as state project and the journalism as genocide and called for a more severe look at the way journ is progressing especially of online news and media channels.

Setalvad gave two examples of this point by referring to local newspaper Vijaya Karnataka that continues to spread hate speech and India Today’s coverage of the Tablighi Jamaat incident that campaigned Muslims as “corona spreader and super spreader.”

“Persons in positions of power need to be penalised for hate speech. Article 19 is not touched by hate speech. If an already organised community is targeted by repeated hate by people in power then Article 19 and 20’s non-discriminatory rights are affected,” she said.

Similarly, feminist historian Uma Chakravarti built on the notion that people in power sell hatred. However, she further added that “we have to promote humanity.”

Remembering the killing of Mahatma Gandhi, she said, “We need to consider the history of who we are and as citizens what kind of society we will build. After Gandhi’s murder, everyone wanted a society where all people have rights and securities. When I went to school in the south, I never saw any disc. The hatred seen now was never seen in the public sphere,” she said.

Chakravarti argued that the reason for this stark difference is that nowadays hatred rather than love, humanity, citizenship has been normalised.

“Hatred has been made legitimate. Hate speech is almost normal. What might have been said behind closed today is said on the public podium,” she said pointing out that one only needs to look at the family WhatsApp group to understand this.

She raised concern about the growing acceptability of hatred and people’s lack of reaction to hate speech seen on social media. Chakravarti emphasised that free speech and hate speech require a balance where generating hatred against a community is understood as violence.

“Today we have labelled the hatred corona but even before that such hatred had already begun,” she said.

Chakravarti said that before the coronavirus pandemic there was a political pandemic and referred to the citizenship amendment in 2003. The amendment created a bond between her and others such as Shaheen Bagh icon Bilkis Bano who claimed that she could tell the history of seven generations of her family but could not produce a document to prove it.

She lauded the anti-CAA protests and the farmers’ struggle that recorded two great public outpourings. Similarly, she praised women student Pinjra Tod activists who understood that “pinjras” (cages) existed outside hostels as well. She also highlighted that recent protests had recorded a large number of women activists being picked up and thrown in jail.

She ended by saying that she still hoped for a better India illustrating a secular example wherein a Muslim labourer got off a truck taking him home to stay with a dying Hindu labourer. The Muslim person ensured a proper funeral for the fellow worker personifying Chakravarti’s hope that, “We can still build a better India.”

Related:

A 2020 Report of 10 Worst Victims of Apathy: India’s Migrant Workers

Inequality has gotten sharpened in India: Teesta Setalvad

Migrant Diaries: The story of Zia ul Sheikh

Activists denounce Babri Masjid demolition judgment