On January 27, 2025, the Supreme Court delivered a significant split verdict in a case that underscored the tension between constitutional freedoms, religious identity, and societal discrimination. The case revolved around a plea by Ramesh Bhaghel, a tribal Christian from Chhattisgarh, who sought the court’s intervention to bury his father either on his private land or in the traditional tribal burial ground of his village. The opposition to his request stemmed from his father’s conversion to Christianity, with the village gram panchayat and local community asserting that Christians were not entitled to use the burial ground reserved for their Hindu tribal ancestors. The Chhattisgarh High Court upheld this exclusion, effectively relegating the petitioner to a distant Christian burial ground. This appeal, therefore, became a litmus test for the judiciary’s commitment to addressing systemic religious discrimination and balancing individual rights against societal norms.

The case presented a complex legal challenge at the intersection of Articles 14, 15, 21, and 25 of the Indian Constitution, raising questions about equality, religious freedom, and the right to dignity in death.

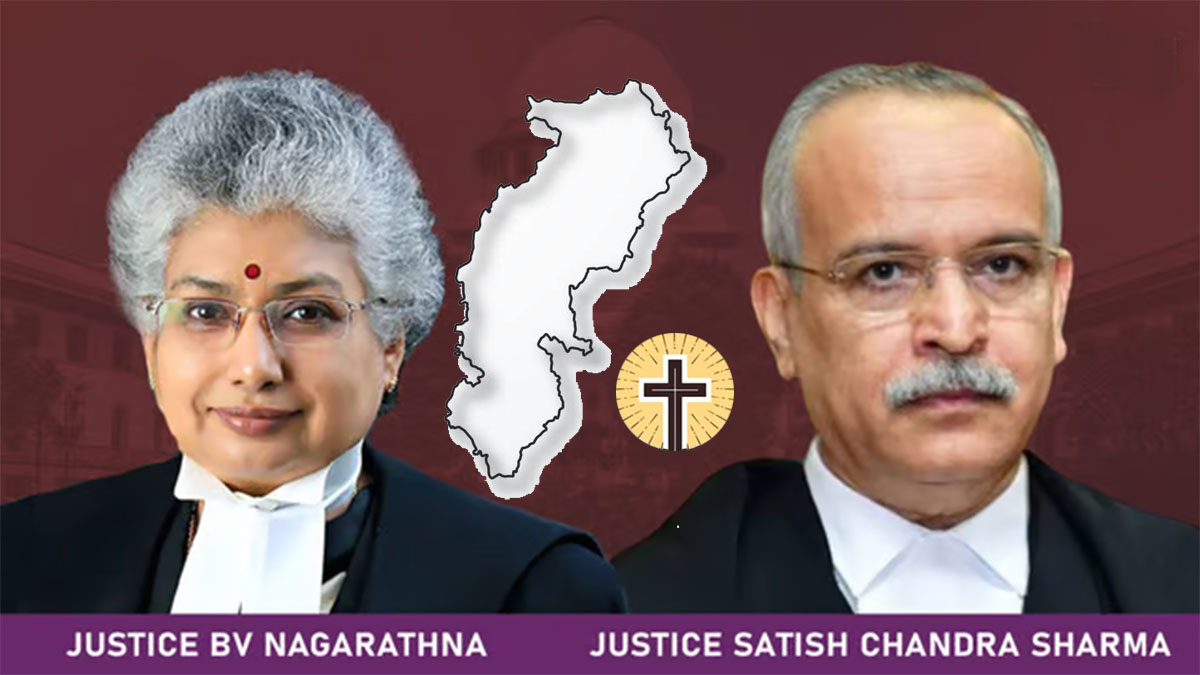

With the Supreme Court’s two-judge bench issuing divergent opinions, the matter brought to light the judiciary’s struggle to reconcile competing interests. Justice BV Nagarathna delivered a progressive opinion firmly rooted in constitutional values, calling out the State and local authorities for perpetuating discrimination against Christians and emphasising the secular fabric of India.

In contrast, Justice Satish Chandra Sharma’s opinion prioritised public order and adherence to regulatory norms, reflecting a more conservative approach that arguably overlooked the structural inequities at play.

The court’s eventual compromise, directing the burial at a designated Christian graveyard under Article 142, addressed the immediate dispute but left broader constitutional questions unresolved, raising critical concerns about the judiciary’s handling of systemic discrimination.

Justice BV Nagarathna’s opinion: A strong defence of Constitutional values

Justice BV Nagarathna delivered a strongly worded opinion, criticising the State and the gram panchayat for perpetuating discriminatory practices against Christians and undermining constitutional principles. She described the refusal to allow the burial in the village graveyard as “unfortunate, discriminatory, and unconstitutional,” explicitly highlighting its violation of Articles 14 (equality before the law), 15 (prohibition of discrimination on grounds of religion), and 21 (right to dignity, which includes dignity in death).

As per the report of LiveLaw, Justice Nagarathna noted that the village panchayat’s actions and the affidavit submitted by the Additional Superintendent of Police (ASP), which opposed the burial, “betray the sublime principle of secularism.”

She observed:

“The refusal to bury the deceased in the ancestral village graveyard violates Articles 21 and 14 and furthers discrimination on the grounds of religion. The State cannot deny equality before the law.”

According to the LiveLaw report, Justice Nagarathna further criticised the State for failing to act against discriminatory attitudes, asserting that it had abdicated its duty to foster fraternity and ensure equality. It was her opinion that the attitude of the village panchayat gave rise to hostile discrimination, and such an approach betrays the secular fabric of our nation and the duty of every citizen to foster fraternity.

“How could ASP Bastar could give such an affidavit and what was the authority? It betrays the sublime principle of secularism. Secularism along with fraternity is a symbol of brotherhood between all faith and essential for the social fabric of our country and duty is to foster fraternity among different sections,” her opinion said as per Bar and Bench.

Justice Nagarathna proposed a pragmatic solution by allowing the burial on the family’s private agricultural land, emphasising that such a decision would not set a precedent for future claims. She directed the State to provide security to ensure that the burial could proceed peacefully and issued an additional directive requiring the State to earmark burial grounds for Christians across all districts within two months.

“The State must act to ensure that designated burial grounds for Christians are available throughout the State to avoid such controversies in the future.”

Justice Nagarathna invoked the Supreme Court’s past observations on secularism and fraternity, quoting Justice Chinnappa Reddy’s iconic statement in the Bijoe Emmanuel case:

“Our tradition teaches tolerance, our Constitution teaches tolerance, let us not dilute it.”

In short, through her opinion, Justice Nagarathna made the following key observations-

- Upholding secularism: Justice Nagarathna invoked the secular ethos of the Constitution, condemning the exclusionary practices of the gram panchayat and the State’s endorsement of such discrimination. She stressed that secularism entails equal treatment of all faiths and criticised the affidavit submitted by the State police, which explicitly denied burial rights to Christians in tribal burial grounds.

- Right to dignity in death: Justice Nagarathna’s recognition of the right to dignity in death as a part of the broader right to life under Article 21 is a crucial highlight. By directing the burial on private land, she sought to balance individual rights with practical considerations, though this move might inadvertently dilute the case’s central question of access to public burial spaces.

- Critique of Gram Panchayat: Her rebuke of the gram panchayat for “taking sides” underscores the growing politicisation of local governance bodies in communal disputes. However, her reliance on the private land solution, while pragmatic, could be criticised for sidestepping the long-term structural issue of discriminatory burial practices.

- Mandating systemic reforms: Justice Nagarathna directed the State to demarcate burial grounds for Christians across all villages within two months, a step that, while commendable, reflects a reactive rather than proactive approach by the judiciary in addressing systemic inequities.

Justice Satish Chandra Sharma’s opinion: Balancing rights and public order, no matter the cost

In contrast, Justice Satish Chandra Sharma took a more conservative stance, focusing on public order and adherence to existing regulations. He upheld the Chhattisgarh High Court’s decision to deny burial in the village graveyard and ruled that the deceased should be buried in the designated Christian burial ground located 20–25 kilometres away. Justice Sharma argued that burial rights under Article 25 (freedom of religion) must be subject to reasonable restrictions, including public order and State regulations.

“There is no reason why there should be an unqualified right to burial. Sweeping and illusionary rights can lead to public order disruption. Maintenance of public order is in the larger interest of society.”

As per the report of Bar and Bench, Justice Sharma also dismissed the argument that burial in the village graveyard was a constitutional entitlement, stating:

“The right to religious freedom under Article 25 cannot be stretched to claim a blanket right to be buried in grounds earmarked for another religion.”

Justice Sharma, according to LiveLaw, reasoned that the availability of a designated Christian burial ground nearby was sufficient to satisfy the petitioner’s rights, noting that burial grounds are traditionally designated for specific communities to avoid conflicts.

“To claim Article 25 rights to burial in areas designated for another faith would be stretching the right beyond reasonable limits. The State can frame regulations to maintain public order.”

Justice Sharma’s opinion ultimately prioritised regulatory uniformity and social harmony over addressing systemic discrimination, a perspective criticised for lacking sensitivity to the petitioner’s plight and the broader implications for minority rights. In short, through his opinion, Justice Sharma made the following key observations-

- Deference to local practices: Justice Sharma’s reliance on the High Court’s reasoning—that burial grounds are designated for specific communities—risks legitimising exclusionary practices rooted in social prejudice. By framing the dispute as a matter of public order, his judgment arguably prioritised societal biases over constitutional values.

- Regulatory formalism: His rejection of burial on private land and insistence on using the designated Christian burial ground in Karkapal highlights a strict adherence to regulatory frameworks. However, it also underscores a reluctance to question systemic discrimination in such frameworks, even when they conflict with fundamental rights.

- Public order vs. individual rights: While public order is a valid constitutional limitation under Article 25, Justice Sharma’s reasoning effectively places an undue burden on minority communities, forcing them to accept segregationist practices. This approach risks emboldening majoritarian pressures, particularly in deeply polarised societies.

Article 142 directions: A compromise that misses the larger picture

The Supreme Court’s decision to invoke Article 142 to direct the immediate burial of the deceased at the designated Christian graveyard in Karkapal reflects a pragmatic approach to resolving the immediate dispute.

While this direction ensured that the petitioner could proceed with the burial without further delay, it falls short of addressing the deeper constitutional and social issues raised by the case. The Court’s reliance on Article 142 to avoid a prolonged legal battle highlights an attempt to balance competing interests, but it also exposes significant gaps in judicial engagement with structural discrimination.

One of the most troubling aspects of this compromise is the Court’s avoidance of the core constitutional issues at stake. Instead of referring the matter to a larger bench to decisively address whether the denial of burial rights in the village graveyard amounted to unconstitutional discrimination, the Court settled for an ad hoc resolution. This avoidance not only leaves the fundamental question of the constitutionality of such practices unanswered but also risks setting a precedent where urgent cases involving marginalised communities are reduced to temporary, case-specific solutions. By failing to engage with the broader principles of equality and secularism, the Court missed an opportunity to lay down a robust precedent that could guide future disputes of a similar nature.

The compromise also reinforces the marginalisation of minority voices. By directing burial at a designated Christian graveyard far from the petitioner’s village, the Court effectively sidelined the petitioner’s plea for equal treatment and dignity. This resolution sends a message that minority communities must navigate systemic biases rather than challenge them outright. The petitioner’s demand for burial in the village graveyard was not just a logistical issue but a symbolic assertion of equality and belonging. The Court’s failure to address this demand perpetuates the notion that minorities must acquiesce to discriminatory practices, thereby entrenching their exclusion from shared communal spaces.

While the invocation of Article 142 served to bring an end to the immediate crisis, the compromise falls short of delivering substantive justice. It highlights a judicial tendency to focus on expediency at the expense of confronting structural inequalities, leaving marginalised communities to grapple with the long-term consequences of systemic discrimination.

Critical reflections: Judicial challenges in addressing discrimination

The Supreme Court’s handling of the burial dispute raises important concerns about the judiciary’s approach to balancing constitutional values against public order, systemic discrimination, and local governance. A closer examination of the case reveals troubling trends that demand critical scrutiny.

First, Justice Sharma’s emphasis on maintaining public order over upholding individual rights reflects a growing judicial inclination to privilege peace and harmony over addressing the legitimate grievances of marginalised communities. While public order is undoubtedly an important consideration, prioritising it in this manner risks reinforcing entrenched biases rather than dismantling them. In cases involving historically marginalised groups, such an approach undermines the transformative potential of the Constitution by legitimising social hierarchies under the guise of pragmatism.

Second, the Court’s avoidance of structural issues highlights a broader hesitation to confront systemic inequities. By focusing on short-term solutions, such as imposing a two-month deadline for demarcating burial grounds for Christians, the Court addressed only the immediate logistical concerns without tackling the underlying issues of social exclusion and prejudice.

The decision stops short of questioning whether the segregation of burial grounds is constitutionally permissible, thereby missing an opportunity to challenge practices that perpetuate discrimination.

Third, the case underscores the politicisation of local governance bodies, which often act as enforcers of communal divides rather than mediators of inclusive policies. Instead of protecting the rights of all citizens, these institutions have increasingly become instruments of exclusion, driven by majoritarian pressures. The judiciary must play a more active role in holding local governance bodies accountable to constitutional principles, ensuring they act as facilitators of inclusion rather than agents of division.

Finally, the intersection of caste, religion, and conversion brought to light by this case reveals the persistent hostility faced by tribal Christians. These individuals often occupy a precarious position, trapped between their ancestral identity and their chosen faith. Conversion to Christianity frequently becomes a basis for denying them access to ancestral land or communal spaces, exacerbating their social exclusion.

The judiciary must ensure that constitutional protections extend to all citizens, irrespective of their faith or choice to convert, and that conversion does not become an excuse for perpetuating discrimination.

Together, these reflections highlight the need for a more proactive and transformative judicial approach to address structural inequalities and protect the rights of marginalised communities.

Broader implications: The judiciary’s role in addressing systemic discrimination

The split verdict in this case underscores the judiciary’s ongoing struggle to reconcile constitutional principles with the realities of an increasingly polarised society. Justice Nagarathna’s dissenting opinion serves as a vital reminder of the judiciary’s fundamental duty to uphold constitutional values and protect the rights of marginalised groups. Her emphasis on equality and non-discrimination reflects the transformative vision of the Constitution, which seeks to dismantle systemic inequities and foster inclusivity.

However, the lack of a decisive resolution on the fundamental issue of discriminatory burial practices reveals the judiciary’s limitations in confronting entrenched societal biases. By failing to refer the matter to a larger bench or deliver a definitive ruling, the Court has missed an opportunity to provide clarity and enforce constitutional safeguards against discrimination.

This case also brings to light the pressing need for legislative reforms aimed at ensuring equal access to public burial grounds for all communities, irrespective of caste, religion, or conversion status. The judiciary’s reliance on public order as a justification for discriminatory practices risks normalising exclusionary behaviour, allowing prejudices to persist under the guise of maintaining peace. Legislative intervention is critical to prevent such misuse of public order and to establish clear, enforceable guidelines that uphold the principles of equality and secularism.

In a country as diverse as India, disputes of this nature challenge the foundational ideals of the Constitution, particularly secularism and equality.

The resolution of such cases serves as a litmus test for the judiciary’s commitment to addressing systemic discrimination and safeguarding the rights of marginalised groups. While pragmatic solutions may provide immediate relief, they fail to address the deeper social and institutional barriers that perpetuate exclusion. To truly uphold constitutional ideals, the judiciary must adopt a more assertive stance, one that not only resolves individual disputes but also challenges the systemic biases that underlie them.

Related:

Sambhal Custodial Death: A systemic failure exposed

Eradicating Stigma: A Landmark Judgment on Manual Scavenging and Justice for Dalits