“While the veneer of cultural syncretism helps to maintain the image of an essentially pluralist and inclusive character of Hinduism, there is systematic and violent exclusion of Muslims from the body politic of the Indian nation.”

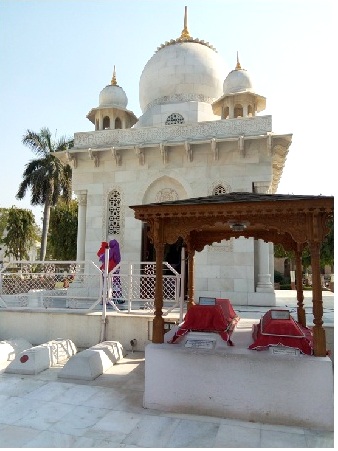

Saraspur Roza, where Ehsan Jafri is buried/ Image Courtesy: Heba Ahmed

The UNESCO has given the designation of a World Heritage City to Ahmedabad, the first of its kind in India. The declaration was followed by self-congratulatory statements by Vijay Rupani, the Chief Minister of Gujarat and Amit Shah. Ruchira Kamboj, India’s permanent representative to the UNESCO, said that Ahmedabad deserved the status of a heritage city because of its long history of unity among different communities and its confluence of different architectural traditions. The status of a UNESCO heritage site increases the brand value of a city and popularises it as a tourist destination. The recognition by UNESCO is the result of two decades of “heritage cultivation”. The Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation established a heritage cell in 1996, which was later upgraded into a Heritage Department. The AMC also started a Heritage Walk in 1997.

A UNESCO tag, especially one endorsed by men like Shah and Rupani, helps to bolster the image of Ahmedabad as a folksy city with syncretic cultural traditions. The syncretism of Ahmedabad appeals to Gujarati asmita: the cultural pride of belonging to Gujarat, which extends from the rhetorical “five crore Gujaratis” featuring in Narendra Modi’s speeches to the Gujarati diaspora, consisting mostly of caste Hindus. The asmita of Gujarat was orchestrated in the gaurav yatra undertaken by Modi in 2002 in the immediate aftermath of the anti-Muslim pogrom; the yatra helped refurbish Modi’s image against his critics and also deflected any condemnation of the killings of Muslims. In a similar way, nostalgia about Ahmedabad’s heritage carefully avoids mentioning any destruction of architectural heritage. Episodes of violence disrupt seamless chronicles of urban heritage; hence, there is a silence about how Hindutva mobs tore down the iconic shrine of Wali Gujarati in 2002, to be replaced by a tarred road built under the Ahmedabad municipality’s supervision.

While the veneer of cultural syncretism helps to maintain the image of an essentially pluralist and inclusive character of Hinduism, there is systematic and violent exclusion of Muslims from the body politic of the Indian nation. This contradiction is mirrored in the narrative of urban heritage in Ahmedabad: it is claimed to be inter-cultural, but excludes many spaces which do not fit the neat definition of national monuments. Just like the asmita of Modi’s gaurav yatra spelled acartography of anti-Muslimness, descriptions of Ahmedabadi heritage make scarce mention of Muslim cultural spaces.

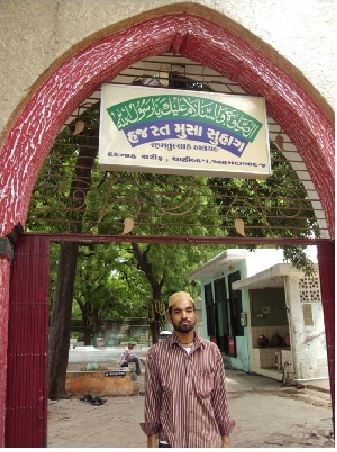

Dargah of Hazrat Moosa Suhaag in Shahibagh, Ahmedabad/ Image Courtesy: Heba Ahmed

Take for example, the website of “The House of Mangaldas Girdhardas – An Urban Heritage Hotel”, which claims to have devised “three Heritage Walks that give visitors an unforgettable glimpse into six hundred years of history that is continuing to evolve today.” The website portrays the old city of Ahmedabad, the part which has earned the UNESCO tag, as “a tightly condensed humanity going about daily chores as if time had stood still, with chaotic bazaars, crisscrossing narrow streets (called “pols”) punctuated by beautifully carved bird feeders, roaming cattle, crumbling but stunning examples of vernacular architecture and artisan workshops.” This description infantilises the lives of a large section of Muslims who live in the old city. It is unclear what “vernacular architecture” refers to; perhaps it is hinting at shrines like the Chalte Pir ki Dargah in Mirzapur, or the Hazrat Moosa Suhaag’s Dargah in Shahibagh in the old city. These dargahs are very popular and have a daily assemblage of visitors and worshippers. But their location in the midst of Muslim ghettos makes them unsuitable for inclusion in the list of heritage tourist spots advertised in different Heritage Walks.

Chalte pir ki Dargah in Mirzapur/ Image Courtesy: Heba Ahmed

Another blog says that the “pol culture brings us back to the age when Ahmedabad was known as the Manchester of India. Heritage of these pols has helped Ahmedabad gain a place in UNESCO’s tentative lists.” A pol is a cluster of houses, usually with the same caste location. Following the 2002 pogrom, most of the pols in eastern Ahmedabad have become even more homogenously demarcated. While Hindus have shifted to western Ahmedabad where Muslims are less in number, Muslims too have moved to places like Juhapura, a large Muslim ghetto far removed from the main city. These accounts of violence and separation are blithely ignored by tourist brochures celebrating the diversity of pol life.

In his essay, “Imperialist Nostalgia”, Renato Rosaldo writes, “Nostalgia is a particularly appropriate emotion to invoke in attempting to establish one’s innocence and at the same time talk about what one has destroyed. The relatively benign character of most nostalgia facilitates imperialist nostalgia’s capacity to transform the responsible colonial agent into an innocent bystander.” He insists that “imperialist nostalgia uses a pose of “innocent yearning” both to capture people’s imaginations and to conceal its complicity with often brutal domination.” Majoritarian nostalgia rides roughshod over the minority’s trauma of exclusion.

The cultivation of Gujarati heritage in Ahmedabad has permitted private stakeholders like heritage hotels to chart heritage walks and promote heritage tourism. But as Dia Da Costa explains in her essay “Sentimental Capitalism in Contemporary India: Art, Heritage and Development in Ahmedabad, Gujarat”, heritage tourism also involves urban reconstruction, which is a euphemism for the exclusion and displacement of marginalised communities. Da Costa writes, “while depicting images of Hindu worship on riverbanks, mosques are conspicuously absent.” The UNESCO designation has spurred talks about heritage conservation and protecting ASI sites from encroachment and illegal construction. But these lofty entrepreneurial endeavours disregard the lives and narratives of those people who have witnessed the violent destruction of places where they live and pray. And their efforts at rebuilding these places are not supported by those who officiate at heritage cultivation.

Dargah of Ladla pir in Shahibagh/ Image Courtesy: Heba Ahmed

Jameela Khan lives near the Jamalpur Darwaza in Ahmedabad. She is a member of both the Bharatiya Muslim Mahila Andolan and the Jamaat-e-Islami. Referring to the Ishanpur Masjid which was partially damaged during the pogrom in 2002, she alleges that the Waqf board has not done anything to rebuild mosques and dargahs or to protect them from destruction in the first place. She herself has led an agitation for the maintenance of mosques and graveyards. In Shahibagh, at the dargah of Ladla pir, Mehboob bhai, his wife Kamrun-nisa and their two daughters took over the responsibility of care and protection of the dargah from Mehboob’s father, Anwar Mirza. In 2002, the dargah was attacked by the marauding tolas and the family had to seek refuge in a relief camp at the Dariya Khan Gumbat. Kamrun-nisa says that over the years, especially after 2002, the status of this dargah has been declining. She resents the fact that the Ladla pir is considered a “lesser” saint compared to other prominent Sufi shrines in Ahmedabad. She wants to construct a boundary wall to prevent encroachment upon the hospices of the dargah, but her non-Muslim neighbours have opposed it.

At Ma Fateshah’s dargah in Shahibagh, the khadim, Syed Anwar Hussain says that Ma Fateshah was the daughter of the celebrated saint, Hazrat Shah Alam (1415-75) of the Suhrawardi order. This dargah faced heavy damage during the 2002 pogrom. Anwar Hussain remembers how the tolas tore up copies of the Koran, destroyed the mazaar or the grave of the saint, and looted their belongings from their homes. He says that he has not received any compensation from any agency; only public donations from worshippers have made the restoration work possible. Anwar Hussain and Mehrun-nisa, his wife, had taken shelter at the relief camp of Dariya Khan Gumbat for six months before returning to cleanse the dargah. He emphasises that since the patron saint of the dargah is a woman, the dargah was made “paak-saaf”(clean and pure) by the services of women alone.

Gulbarg Society in Ahmedabad during the 2002 riots/ Image Courtesy: The Hindu

Qasambhai Mansuri is the only survivor of the Gulbarg Society massacre who has rebuilt his damaged home and returned to live there, despite losing nineteen members of his family in the massacre. He narrates that he took it upon himself to rebuild the mosque located on the premises of the Gulbarg Society and to renovate the dargah of Sheikh Jalaluddin which stands nearby.

Dargah of Sheikh Jalaluddin near the erstwhile Gulbarg Society/ Image Courtesy: Heba Ahmed

For each of these survivors of violence, the history of Ahmedabad is replete with episodes of anti-Muslim violence. But their memories of violence do not feature in official accounts of heritage-building in Ahmedabad. The mosques and dargahs which have withstood damage and destruction are located in the old walled city, the area that has earned the moniker by UNESCO. Irony lies in the fact that even while the old city is hailed for its architecture and cultural traditions, the Muslims who live in those spaces have suffered systemic disempowerment. The sanitised versions of Gujarati heritage in Ahmedabad make no mention of places like the Saraspur Roza wherein lies the grave of Ehsan Jafri.

Ehsan Jafri with his daughter/ Image Courtesy: firstpost

Recently, a ghazal written by Wali Gujarati was included in a Hindi textbook issued by the Gujarat State School Textbook Board. But there was no mention of the demolition of his grave. Wali’s ghazal is a reflection of the pain of separation from his homeland:

“Gujarat ke firaq se hai khaar khaar dil,

Betaab hai seenay mein atish bahar dil,

Marham nahin hai iske zakhm ka jahan mein,

Shamshir e hijr se jo hua hai figar dil.”

Read an extract from Harsh Mander’s book Fatal Accidents of Birth here: From Godhra to Una.

Read Rajendra Chenni’s essay on the loss of syncretic culture in Karnataka here: In Dispute

Heba Ahmed is a Ph. D. Research Scholar at the Centre for Political Studies, JNU. Her M.Phil. dissertation was titled “Remembering Gujarat 2002: Contending Memories and the Politics of Violence.”

Courtesy: Indian Cultural Forum