Regarding the criminal law provisions, a report points to abuse of the procedural law.

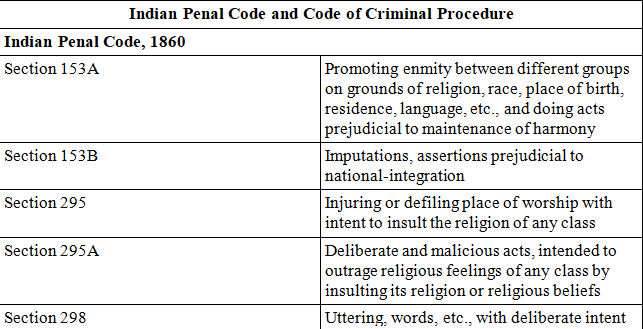

The first provision the report dealt with was section 153A of the IPC. This provision criminalises promoting enmity between social and religious groups. The finding regarding this section was that the judiciary has consistently held intention as a central component to establish an offence under this section. The provision, however, falls short in terms of restricting speech that promotes enmity on the basis of gender. The defence of ‘truth’ has not always been allowed and instead, the judiciary has tended to view the likely effect of the representation rather than its truth. Section 153B of the IPC supplements 153A as well as 295A. The provision extends liability to publishers as well as those who reiterate the content. While intention has been an important ingredient regarding section 153A, it has not been accorded equal weightage in adjudicating cases under 153B.

Section 295 of the IPC deals with injuring or defiling a place of worship with the intention to insult. This section too places a premium on intention as an ingredient. However, the intention to insult must also be accompanied by an injury. The injury, on the other hand, need not be physical damage. The section also includes objects that are held sacred. Regarding speech, that may be termed ‘defilement’, the Courts have exempted narrations of acts of defilement, whereas commentary constituting ‘defilement’ has been punished.

Section 295A of the IPC deals with deliberate and malicious acts to outrage religious sentiments. The Courts have placed a high threshold for determining whether an act constitutes an offence under this provision. This is to ensure that the critique in good faith to bring about social reform is not punished. Under this provision, truth is not a valid defence if all the other ingredients are proved – primarily the deliberate and malicious intention. The report however argued that “Section 295A is a disproportionate measure since forfeiture and other means of prior censorship are available to the government. The threat of arrest and conviction in this context is not necessary to preserve public order, and it does create a great risk of chilling freedom of expression.”

Section 298 of the IPC deals with uttering words with an intention to wound a person. This section places a lower threshold than 295A regarding proving the offence. However, the onus is on the State to prove that the accused had a deliberate intention. Unlike section 295A, which applies to a class of people being insulted, section 298 applies to an individual.

Section 505 of the IPC is a broad provision dealing with several acts amounting to public mischief. However, in the context of hate speech, subsection 2 is relevant. Section 505(2) deals with statements creating or promoting enmity or ill-will between classes of persons. The provision primarily deals with spreading rumours. This provision concerns instances where the statements were made with an intention to cause mischief, as well as where the likely effect is to cause mischief. The judiciary, on its part, has opted to interpret this provision conservatively, in order to prevent its abuse.

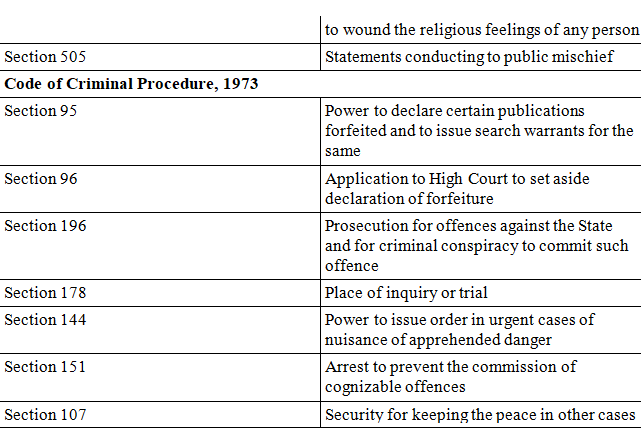

Moving on to the CrPC provisions, the report began with sections 95 and 96, which authorise the state government to forfeit any book, newspaper or document whose publication is punishable under the above mentioned IPC sections. The report found that while section 95 authorises the state government to forfeit offending publications, section 96 allows appeals against the order for forfeiture. However, the role of the judiciary is limited only to determining the validity of the grounds of forfeiture. The Bombay High Court had extended the provision for appeal to the general public, rather than only the aggrieved publisher. A problem with section 95, however, is that the Order for search and seizure is to be published in the official gazette, whereas readers and publishers may not always be aware at the time of publication. Thus, publishers would tend to err on the side of caution, thus effecting a policy of self-censorship.

Section 196 of the CrPC deals with sanction for prosecuting offences against the State and for criminal conspiracy to commit such offences. The requirement of sanction prior to cognisance acts as a safeguard against frivolous complaints being filed. However, the provision does not prevent the allegations from being investigated, or the police from arresting a person in connection with the offence. The report considered the National Crimes Record Bureau figures for 2015, where 941 persons were arrested for offences promoting enmity between groups. The report also mentioned that this provision does not prevent sedition laws from being invoked indiscriminately. Thus, the provision does not prevent harassment even though sanction may not be granted.

The report also looked at other CrPC provisions, which may not be directly related to hate speech. Section 178 provides for the place of trial. Under this section, if the place where the offence was committed is not known or if the offence has been committed at several places, any court, whose jurisdiction the offence has occurred in, can hear the matter. This provision was used in late painter M. F. Hussain’s case, where complaints were filed in numerous jurisdictions for the same work of art. The Delhi High Court had acknowledged the threat to free speech that this provision entailed, when it allowed the complaints to be compiled and be heard in Delhi as one case.

Section 144 of the CrPC concerns prohibitory orders for case of nuisance or apprehended danger. The provision states that there must be an imminent danger requiring immediate remedy. The order, in this regard, must be in writing and based on material facts. The order must state the specific acts that are prohibited. The duration of the order must also be co-extensive with the duration of the emergency. The report noted that this provision has been used repeatedly to curb free speech though internet shut-downs in Gujarat, Bihar, and Jammu and Kashmir.

Sections 107 and 151 deals with preventive detention. Section 107 provides for the Magistrate to order persons to execute bonds for ‘good behaviour’, or promise to abstain from doing any particular act. This provision is effected when there is an apprehension that there is likely to be a breach of peace. Section 151, on the other hand, empowers the police to arrest persons without a warrant, where the officer is aware of a design to commit an offence.

Summing up, the findings regarding the criminal law regarding hate speech have shown that the laws tend to be abused for more than their intended purpose. The judiciary, in interpreting the IPC provisions, has tended to place a premium on proving intention. Truth is not always treated as a valid defence – particularly, when the effect of the speech or publication can affect public tranquillity, even though violence does not occur. The law is silent on speech and publications causing ill-will on the basis of gender. The Courts, on their part, have upheld these IPC provisions under the reasonable restrictions contained in Article 19(2).

The CrPC, under section 95, allows censorship without judicial review, whereas section 96 can be invoked by an aggrieved party – the Bombay High Court decision may not be accepted by all High Courts – however, even if the order under section 95 is quashed by the Court, the problem here is harassment. Similarly, section 196 provides for sanction to be granted before the court takes cognisance of the offence. However, since this provision does not bar investigation and arrest, the scope for harassment is also quite large. The other provisions too have been abused. The example of section 178 regarding M. F. Hussain lays bare how several complaints can be filed in relation to a single act, thus this provision too is subject to abuse.

This article was first published on newsclick.in.