Vinutha Mallya in conversation with Raosaheb Kasbe

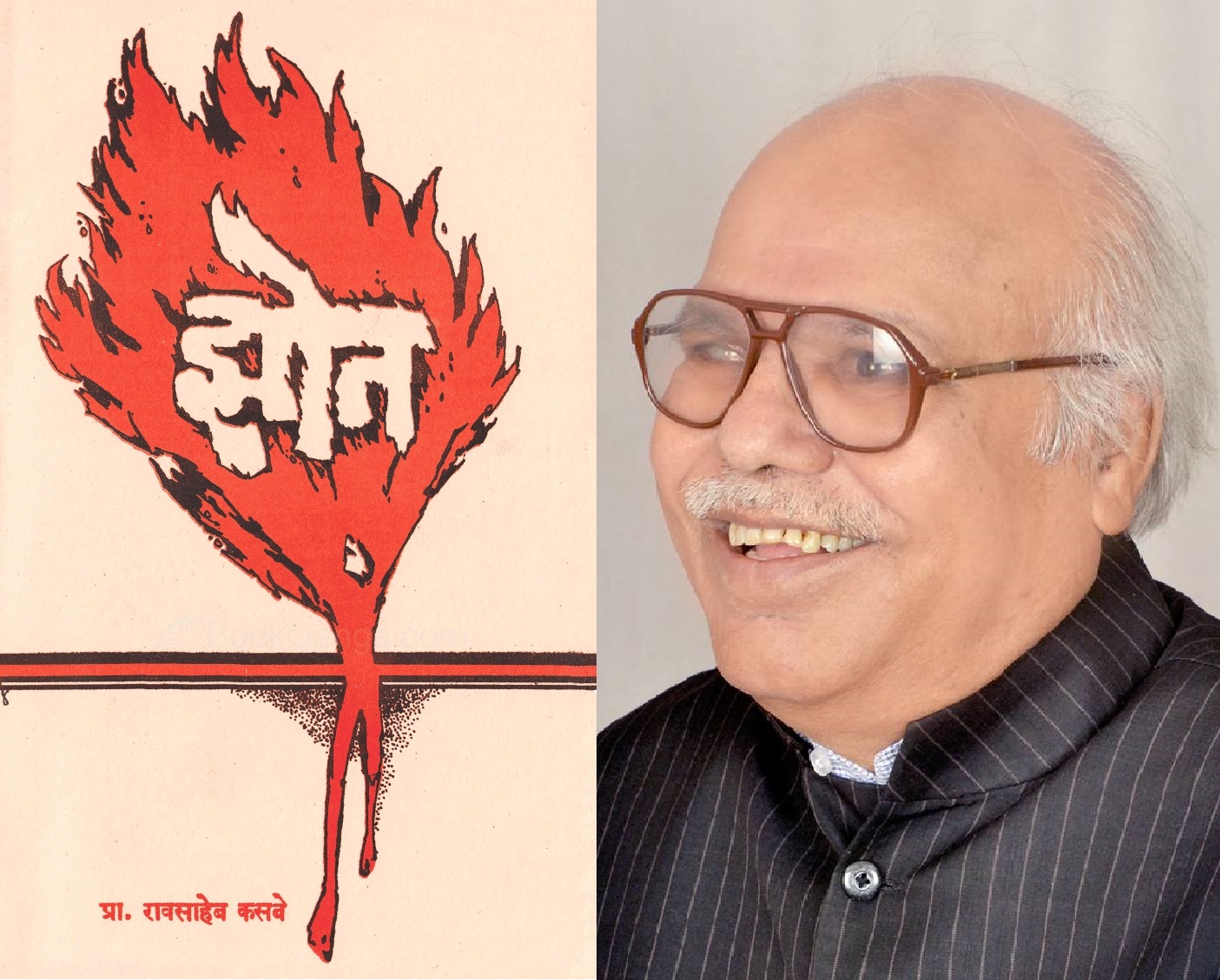

When Raosaheb Kasbe’s Zot was published in Marathi in 1978, RSS cadres made a public bonfire of it at the Janata Party convention in Pune that year. The book presented an incisive critique of M.S. Golwalkar’s Bunch of Thoughts, the main ideological treatise of the RSS. Kasbe traced the historical roots of cultural nationalism as outlined by Golwalkar, and exposed its authoritarianism. His study of the functioning of the RSS revealed its communal blueprint, its anti-modern views and anti-democratic objectives.

Kasbe challenged the RSS on its own turf—its interpretation of Hinduism. Through a rigorous critique of Golwalkar’s text and careful analysis of ancient texts, the scholar showed how the RSS version of Hinduism was unapologetically casteist and deeply patriarchal.

Four decades and seven editions after its first publication, Kasbe’s zestful polemic is finally available for the first time in English, published by LeftWord Books as Decoding the RSS: Its Tradition and Politics. The book has been translated by Deepak Borgave and edited by Vinutha Mallya. The introduction to the book has been written by Shamsul Islam.

In this interview, the author speaks to Vinutha Mallya about the book, and highlights the value of socialism for India.

Vinutha Mallya [VM]: Why did you write Zot?

Raosaheb Kasbe [RK]: When I was a student of MA, I read four books that sparked something in my mind. The first was Karl Marx’s [and Friedrich Engels’] The Communist Manifesto. Then I read Babasaheb Ambedkar’s Annihilation of Caste and Caste in India. After that I read M.S. Golwalkar’s Bunch of Thoughts—it left me disturbed. I decided that one day I must write about this.

After I started teaching at Sangamner College, I began writing articles for newspapers and periodicals like Samaj Prabodhan Patrika, which was one of the best journals in Marathi. I wrote a lot for this publication. In those days, you were considered an intellectual if your writing was published in Samaj Prabodhan Patrika. My writing was noticed by Pu La Deshpande, Vasant Bapat, Vijay Tendulkar, and Kusmagraj. They wrote to me and invited me to meet them whenever possible. I went and met them all at that time.

I had already been teaching at Sangamner College for five years when Zot, my first book, was published in 1978. My second book, Dr. Ambedkar ani Bharatiya Rajyaghatana (Ambedkar and the Indian Constitution), was released a month after that.

VM: How was the book received?

RK: There was a store in the college where the books were kept on sale. The college management consisted of many RSS people. They protested to the principal [M.V. Koundinya] and demanded that the college store stop selling the book because it portrayed the RSS in a bad light. Koundinya said that if I had written a book it must be something good. He sent them back with the advice that they should write something nice about the RSS and get it published. Then the store could sell both books.

At the Janata Party convention in Pune later that year, the problems between the old Jan Sangh and the socialists began to surface. The socialists had kept this book on sale there, along with Baba Adhav’s Sanghachi Dhongbaji (Shenanigans of the RSS). People from the RSS demanded that the book be removed. There was an outbreak of fisticuffs between the two sides. The Jan Sangh group made a bonfire of the book and burnt it in public. I found out about it only the next day in Sangamner. I was on my way to give a talk somewhere and was at the state transport bus stand when I saw a newspaper with my name in the headline, ‘Raosaheb Kasbe’s Zot burnt’.

After it was burnt, Zot kept making headlines in the newspapers. It received a lot of support in Maharashtra, among the socialists, communists, the Dalit Panthers, and even from the Congress. The Congress raised the matter in the state assembly as well. In fact, Indira Gandhi and Jayaprakash Narayan both condemned the book burning and said that it would not kill the ideas that were in it. The book rode on a wave of popularity. It was priced at Rs 5. Pu La Deshpande bought a hundred copies and gifted them to his visitors. Sharad Pawar, who was Maharashtra’s chief minister, also bought a hundred copies to give away. Some freedom fighters in Dhule sold the book standing by the wayside.

Many well-wishers started telling me, out of concern, that the RSS was dangerous. I said that they wouldn’t harm me because they knew it would cause retaliation. But I received a lot of anonymous letters with threats (I didn’t have a phone connection in those days). So things kept going on like this.

VM: You never formally joined a political organisation. Why?

RK: Who will follow its discipline? It is good to remain independent. However, I’ve been friendly with all Left parties.

When my book Ambedkar ani Marx was released at Tilak Smarak in Pune in 1985, it was a big event. S.M. Joshi, a socialist, launched it. One of the speakers was S.Y. Kolhatkar, who was a member of CPI-M’s central committee. There was Republican Party of India’s Dadasaheb Rupwate too. Ram Bapat, professor of Politics in Pune University, was also there. Former chairman of the state legislative council V.S. Page, the socialist leader Nanasaheb Gore, and the noted freedom fighter Bhausaheb Thorat, were in the audience. So I was reassured that many people were with me. But I was also aware that when a person achieves fame, it requires a balancing act. You don’t know when you’ll fall.

VM: What is the relevance of socialism and communism now? Do they have a future?

RK: Whatever is happening here is happening in Trump’s America too. It is the same thing in Brexit England. The situation will continue like this, and the violence will go on until socialism is established. Like Marx said, the criticism of religion is the premise of all criticism. And religious criticism can end only when it becomes clear that the human being forms the core of the world. There will be no contradictions then—and the social and political systems that will work, and move forward, are those that keep the human being as their base.

Capitalism is going through a crisis just now. [Narendra] Modi’s rise is a strong indication that India’s capitalism is in crisis, and he is here to strengthen it. The contradictions [emerging from capitalism] will become stronger one day or the other, and it will lead to an explosion. It will lead to anarchy, and movements will begin from there—with the struggles between the poor and the capitalists. It is socialism that will win this battle. But we need to create a mass movement, no? Who is thinking of a mass movement? Everybody is going behind electoral politics.

There is a lot of illiteracy and lack of discernment just now. India’s people are not yet ready for democracy. That is why in his last speech in the Constituent Assembly on November 25, 1949, Ambedkar warned the country about the social and economic inequalities in our newly formed political democracy. It was a great lecture, which won great applause. But people haven’t read all this; they are now waking up to it because there is a need. Unless economic and social equality arrives in India, nothing will change here.

In the Left movement, people criticise Modi saying he is this and that. I say that Modi’s arrival was imminent—it was to happen. Because the Left failed to do what Marx said is the first thing to do, i.e. the premise of all criticism being religious criticism. We did not do a diagnosis of religion and culture. This is why there are so many illusions about religion in people’s minds. We haven’t tried to dispel these illusions about religion.

The first reason to bring in socialism is caste. But we did not initiate the anti-caste movement. It could not be done until caste converted to varga, class.

The Naxalites are talking about it now because there are many from the Scheduled Castes in that movement. They say ‘Jai Bhim, Comrade’ today. But it should have been said 50 years ago. And, because of not paying attention to the caste system, see what happened to the communists in Bengal. The Communist Party there was seen as a bhadralok party.

VM: Isn’t it said that there is no casteism in Bengal?

RK: This is the thing about communists—they didn’t believe that casteism existed in India. They believed that there was no caste in India, only class. That’s why they called Ambedkar a ‘bourgeois liberal’. Ambedkar raised the question in Annihilation of Caste in 1936. He asked the communists how they were going to bring the revolution, because for revolution you need class. How will you create class? Even between the poor upper caste person and poor lower caste person there is caste conflict. Had anyone thought about it?

VM: There are many misconceptions about Ambedkar and his philosophy.

RK: Ambedkar was asked by a journalist once, ‘What is your political character?’ Ambedkar responded, ‘Is this something you should ask? I am a socialist’. The journalist persisted and said there were many socialists in the Congress too, so why didn’t he join the Congress. Ambedkar replied that the socialists in the Congress were suffocating and he wanted to breathe freely in the open.

Many didn’t understand Ambedkar, including the Left parties. Madhu Limaye once asked me, ‘Was Ambedkar a socialist?’ I felt, what were people saying? They don’t at all read Ambedkar. At least read him first, I said. Later, in his Prime Movers: Role of the Individual in History, Limaye wrote 110 pages on Ambedkar.

They used to think Ambedkar was a sectarian leader and that Gandhi was the tallest leader. But Ambedkar established the Independent Labour Party. How could he have been a sectarian leader? So one set was blinded by Gandhi and the other by Marx. But is every single word of Marx the final truth? Something would have changed, no? Like Stalin said, there is no rulebook on Marxism. It is a dynamic thought; it must keep changing. Ask any question, and Marxists pull out a book, and say, ‘No, no, Marx has said this, Engels has said that, Lenin has said this, Stalin has said that.’ They should state what they want to do.

VM: If you had written Zot now, do you think the responses would be very different and the risk too?

RK:Things are happening exactly like I’ve written in the book, isn’t it? LeftWord should have published this [the English translation] by 1980. But they thought it was a book about religion… Oh, but LeftWord didn’t exist in 1980! [Laughs]

Courtesy: Indian Cultural Forum