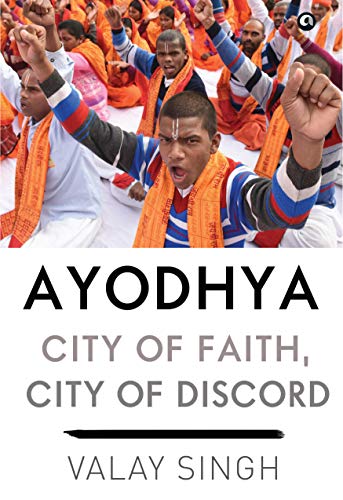

Written by Valay Singh and published by Aleph (2018), Ayodhya: City of Faith, City of Discord is a biography of the city Ayodhya. Over thousands of years, Ayodhya has been a place of reverence for many faiths; but it has also been a place of violence, bloodshed and ill-will. Going back almost 3,300 years to the time Ayodhya is first mentioned, Valay Singh traces Ayodhya’s history, showing its transformation from an insignificant outpost to a place sought out by kings, fakirs, renouncers and reformers and, later, becoming the centre-stage in Indian politics and the political imagination.

The following is an excerpt from the chapter “Scripture, Myth and Reality” of the book.

The Ramayana’s conversion into a divine or holy text began in the second millennium ce. Ram was not always worshipped as a god even though the worship of Ram certainly preceded the emergence of present-day Ayodhya as a centre of Ram worship. Moreover, it was after Tulsidas’s version of the Ramayana appeared in the sixteenth to seventeenth century that Ayodhya became an important centre of pilgrimage in north India and Ram worship grew rapidly. In the following centuries, it would become the most dominant cult, if not the most prevalent one among Hindus.

Ram embodies many values that are attributed to India itself, such as tolerance, secularism, social harmony, equality, moral propriety and courage. As the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) Atal Bihari Vajpayee said, Ram is also to many ‘the symbol of India’s cultural heritage and its national ethos’.1 ‘Ram-bharose’, or ‘thanks to Ram’, is a common phrase heard in high-rises as well as weekly haats. Ram has come to be synonymous with God, at least since the time of the poet-saint Kabir.

It was not always so. Ram worship erupted slowly and quite late in Indian religious history (as evidenced by most Ram temples and Ramayani art dating from the medieval period) and the Ayodhya of today offers us reason to believe that it developed even later as a place of Ram worship. The power of the Ram story as a legitimizing force was used in the fifth century by Vikramaditya (Skandagupta) when he moved his capital from Pataliputra to Saket (Ayodhya). Saket, till then a town with Buddhist and Jain histories, now became the Ayodhya of the Gupta king. After the fall of the Guptas, Ayodhya too faded away till the Gahadvalas rose to power in the aftermath of Ghaznavid raids.2 Bear in mind that this was a time of intense conflict between raiding Muslim armies from the northwest and regional struggles between Hindu kings. It is against the backdrop of a strife-torn political-social landscape that Vaishnavism began to emerge as a religious cult that would subsume many other sects in Hindu life. Some scholars believe that the Gahadvalas built five Vishnu temples in Ayodhya that survived till the time of Aurangzeb.3 However, it is baffling that even after extensive excavations, so little has been discovered of their remains.

Till at least the 1700s, Ayodhya was a regional military centre of the Mughal empire, from where the nawabs of Awadh ruled. It had been in the wilderness for centuries, the continuous armed struggle between the Delhi Sultanate and its feudatories kept the region in turmoil and despite or probably because of that, Ayodhya attracted only the religiously and spiritually inclined of all faiths. In fact, this aspect of Ayodhya needs to be appreciated much more than it has been. Like most pilgrim spots, some parts of today’s Ayodhya offer the spiritual minded, the seeker of peace and the renunciate solace and solitude.

As we have seen earlier, Nageshwarnath, the oldest temple in Ayodhya, is dedicated to Shiva, and as in most of the country, Shiva worship preceded the cult of Ram in Ayodhya as well.4 Shiva is a peer of Vishnu and hence there cannot be a direct comparison between him and Ram, who is the seventh incarnation of Vishnu.5 The six incarnations that precede him are Matsya or the fish avatar, Kurma or tortoise, Varaha or boar, Narasimha or half-man, half-lion, Vaman or the dwarf, and Parshuram or the priest with an axe. Then comes Ram, followed by Krishna of the Mahabharata, and after him, in the Vaishnava tradition, the Buddha as the ninth avatar of Vishnu. The tenth and final avatar is Kalki, a man on a white winged horse; he is to appear at the end of the present cosmic age.

1. Atal Bihari Vajpayee, ‘My musings from Kumarakom–I: time to resolve problems of the past’, The Hindu, 2 January 2001.

2. Vasudha Paramasivan, ‘Yah Ayodhya vah Ayodhya: earthly and cosmic journeys in the Anand-Lahari’ in Heidi Pauwels, ed., Patronage and Popularisation, Pilgrimage and Procession: Channels of Transcultural Translation and Transmission in Early Modern South Asia; Papers in Honour of Monika Hortsmann, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2009, pp. 101–16.

3. Ibid.

4. An inscription on a shivling dated 435–36 ce records a gift for the worship of Mahadeva (another name for Shiva). This shivling was found in the village Karamdande in Faizabad district (Meenakshi Jain, Rama and Ayodhya, New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 2013, p. 95).

5. However, from the Valmiki Ramayana, where Shiva is supposed to have asked Vishnu to manifest as Ram to kill Ravan to the Ramcharitmanas of Tulsidas, where Shiva is shown to be worshipping Ram and narrating the Ramayana to his consort Parvati, Ramcharitmanas marks the ultimate adoption of Shiva by Vaishnavism.

Courtesy: Indian Cultural Forum