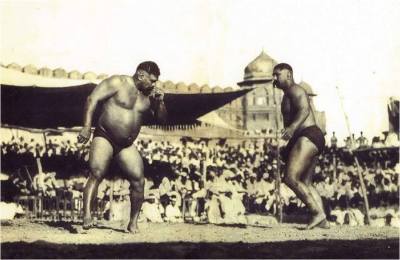

Dangal literally means the Indian style wrestling competition for male pahalwans (wrestlers). Dangal has been an important form of entertainment for ages, especially in rural (north and west) India. Dangals act in many ways. It works to settle the personal score between different Akharas and pahalwans. It’s a place where honour, reputation and social status are on stakes and personal and political rivalries are fought out, or settled. For example, one of the most important dangals used to happen every Sunday at Eidgahi Maidan, Jama Masjid in Delhi, till very recently. Itwari dangal, as it was fondly called, was the place where pahalwan like Gama, Imam Baksh, Chandgiram used to come and show their talent in front of thousands of wrestling lovers. I remember whenever I used to come to Delhi, I always wanted to win the bout at Eidgahi Maidan, as it meant a lot to win at Eidgahi maidan rather than any other place!

As it was strictly meant for male pahalwans, women were not even allowed to watch them fighting, let alone participating. Something similar to Khap Panchayats, where women still are not welcome. Women are the fairly latecomers in wrestling arena and yet not so welcome. In this context to make a film on the emergence and development of women wrestling in India itself is a fascinating idea.

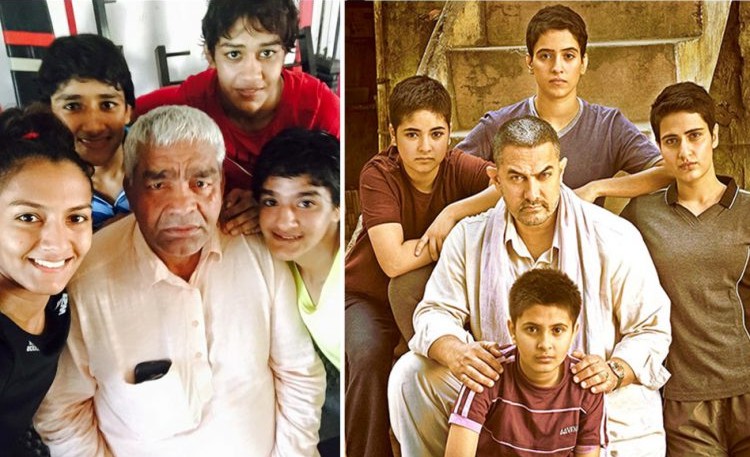

Dangal, the movie is based on a true story of Mahavir and his firebrand daughters and their ‘quietly’ active mother. It is an important movie to watch for many reasons. Firstly, it portrays a father who wanted his daughters to pursue something (wrestling) which was un-imaginable in those days. It reveals what it took for the first generation of women wrestlers to break those masculine stereotypes and depicts the overall impression of wrestling in the realm of sports culture in India. There are so many moments in the film to cheer about, to get goosebumps (at least I got many). Writing review is an unknown territory for me but there is a personal reason to taking to this venture of writing. The release of this film forced me to say something which, as a former wrestler for almost ten years, is still left with me. When Geeta came back from National Sports Academy (NSA), Patiala, she was a changed woman. She is no more a girl who just won the gold medal in national games. She has grown her hair, watched couple of cinemas in Patiala, ate gol guppas, had nail paints etc. These were some moments of pleasure which she was deprived of by her father (Mahavir) in Balali village, Bhivani in Haryana. Mahavir noticed these changes and kept sulking. He didn’t say a word. When she went to her father’s Akhara, she also tried to change the way Mahavir was teaching wrestling till now. Mahavir’s masculinity got hustled and in response he tried to teach Geeta a lesson, but eventually lost to her. This might be seen as one of the passing scenes in the movie, but for me, it says a lot! Mahavir who was always sure about his way of life and teaching was lost to his own daughter whom he taught. It was hard for him to accept. The defeat from his own daughter, a girl, hurt his masculinity deeply. A patriarch was made to taste the mud in his own den. There was no coming back from there. No sign of truce or repentance from Geeta. Masculinity is not always challenged by big events, with a grand opening. Patriarch(ies) are and have been challenged in bits and pieces, in small steps, quietly. That is way too hard to digest and especially difficult when you come from a place like Haryana where women succumb to death in order to break gender stereotypes. Many cases of killing in the name of honour are living example in this region.

Lets take a look at another scene which was appealing in its own narrative. When Mahavir took Geeta to Rohtak to participate in one of the first Dangal of her life, she was looked down upon, taunted, made fun off with her father. In real life it wasn’t one of the easiest moments for Mahavir, let alone Geeta, who was 13 at that time. Women in Haryana are particularly domesticated with all those taunts by men, but men are not warmed up to all these. They don’t know how to take shame. It is as if they are not ready for it. The most commendable thing which came out here is what happened when Mahavir decided to put Geeta in front of thousands of male spectators, no matter how much shame it brings it to him. Eventually, Mahavir and Geeta had the last word. He was more ashamed by the public in general and his clan members in particular. The scene, where she tells his opponent male pahalwan, chori samajhke mat ladiyo, was an evocative one. This says a lot about the ways in which girls have been been typecast by all Haryanvi society and mards around her!

In an appealing scene, which might have been missed by many, Geeta Phogat won the gold medal at Commonwealth Games, 2010 in Delhi. The national anthem was played, but that wasn’t what Geeta was cheering for/ overwhelmed about! She was looking for her father in stands, who wasn’t there! And when she saw him, she ran towards him and gave him the medal. The moment of winning a gold medal at the Commonwealth was a proud moment for her, her father and her family than it was for the country. The film revolves around the personal and social spaces in which Phogat sisters and Mahavir are situated and not in the spaces of nation, nationalism or patriotism. Geeta’s achievement was more pronounced because she fought and won a battle against all obstacles set out by a dominant and exploitative society. She owed her success only to her parents/father and family not to any nation/national sports body. Playing for India was merely a departure moment here and not the defining one. She could see and anyone who has little acquaintance with wrestling and the social circle around it will tell you that the achievement is more important for Geeta (or any other woman wrestler) because it enabled her to overcome the constant fear and shame. It challenges the blindness which denies to see women as equal human being in the region from where she comes from.

Her belief in her father more than the national team coach also confirms the stature of sports (minus cricket) in this country. In this context, I can recall the recent example of Narsingh-Sushil Kumar drama which had reached the court. This incident also shows how contaminated the sports administration in general and Wrestling federation in particular has become. Moreover, the women teams have been thoroughly neglected (materially as well as socially) in order to discourage them rather than encouraging them to fight it out. The coaches have their own favouritism and are least serious regarding the team performances. Not surprisingly, the position of women team’s coach has been considered as a position of punishment. The recent coach of the team (who also assisted Amir Khan in the film) Kripa Shankar was a forgotten/unsung hero who comes from Madhya Pradesh and not from the north lobby (Haryana, Punjab administrators dominate the wrestling’s highest body in India). Even the current Wrestling Federation of India chief, Brij Bhushan Saran Singh, a BJP member of parliament is from Uttar Pradesh and has no distant relationship with wrestling!

In a country, where the cases of women players’ molestation and rampant bias are common, (one must not forget the case of women hockey players who were constantly molested by the head coach and when they raised their voices, they were shown the door), it is important to ask where would one go to regain their strength, assurance, confidence and trust? For Geeta and many others (given the lack of any other spaces to rely upon), it was her father, who became sutradaar to reach where she was in 2010 despite all the odds against women entering the wrestling arena.

The hard-core training could seem comical to some and frustrating to many when they do not understand the context. it is often traumatic, indeed frustrating and could be seen forced, but we must ask are there any other ways to deal with it? The film and the social context might not have a straight sociological answer for that and we may not always look for an answer. On explaining further, it is not easy to get away with caste and gender barriers in a society where lines are demarcated so sharply and doing anything in this regard could be ‘sehat ke liye haanikaarak’ sometime! Mahavir and his daughter did take that risk and overcome it. It may not appear perfect, but for the time being, this attempt/endeavour was necessary.

Sometime the linguistic grammar can not express the grammar of actions and their impact on larger canvas. Mahavir’s life is one such example. He might emerged as stubborn, choleric and unpalatable, but the actions posed throughout the film has larger implications. He was not there to champion the cause of gender justice, but the emergence of Geeta and other women’s barging in the ‘all-male club’ certainly paved the way for that. This is a welcome step, given the limited access to anything ‘social’ to women. This film has its own narrative and it is completely fine if it doesn’t suit our notions and convictions. Mahavir might have won via Geeta through his perseverance, but he lost in bits and pieces, quietly to her as well. Dangal stands apart from many other sports movies (Chak De India, Mary Kom etc.), it neither sets high claims, nor tried to achieve them. It’s a tale of unsung struggles and overcoming them.

Praveen Verma was a wrestler for more than ten years, and ended up in University by chance! He is now doing PhD from Department of History and is also with NSI.

Courtesy: Kafila.online