In the pursuit of a just and inclusive society, access to education plays a crucial role in empowering marginalised communities. However, in India, the educational landscape remains stratified with the Muslim minority grappling with numerous hurdles that impede their educational progress and perpetuate social disparities. Recent academic revelations on the declining enrolment of Muslim students in education and higher education are concerning. The contentious “ban” on hijab (a matter still before the Supreme Court), an all pervasive intimidatory socio-political environment coupled with a push back from sections of the religious clergy are contributory factors.

“The enrollment of Muslim students dropped by 8 per cent from 2019-20 – that is, by 1,79,147 students.” – Christopher Jaffrelot, A. Kalaiyarasan

While the enrolment of Dalits, Adivasis, and Other Backward Classes (OBCs) has increased, the decline in Muslim enrolment is particularly alarming. Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes currently constitute 14.7% and 5.6% of the total enrolment, respectively, while OBCs make up 37% of the student population. In contrast, Muslim students account for only 5.5% of the overall enrolment, with other minority communities comprising 2.3%. It is worth noting that teachers from the Muslim minority group represent 5.6% of the total.

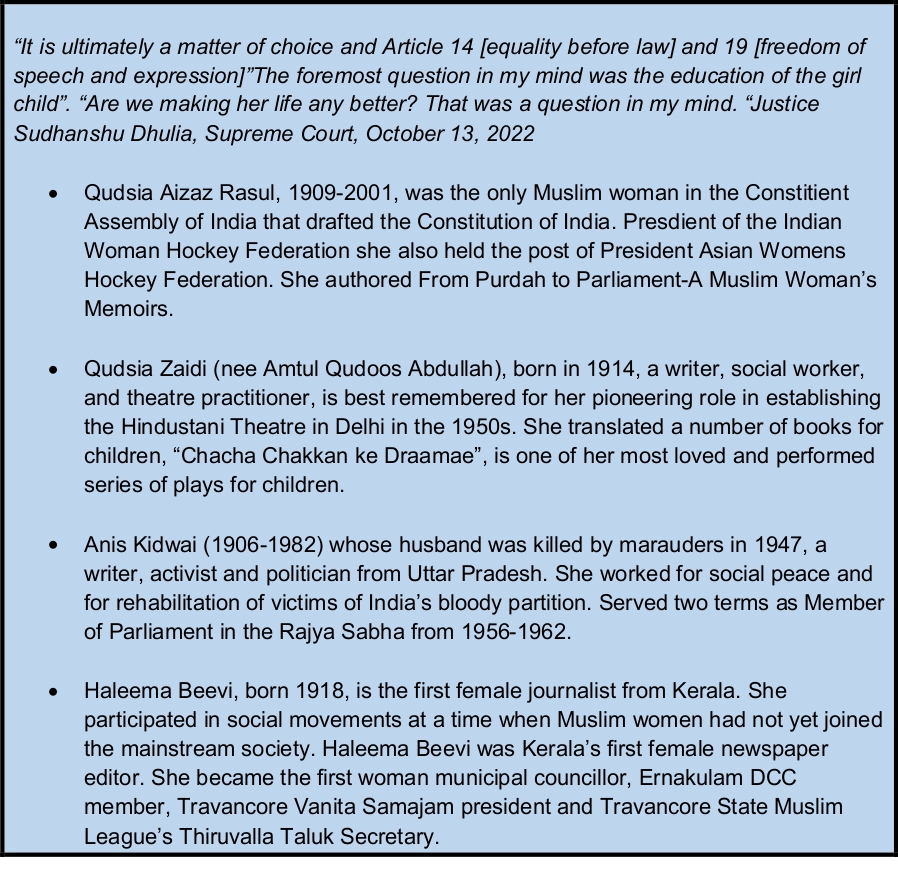

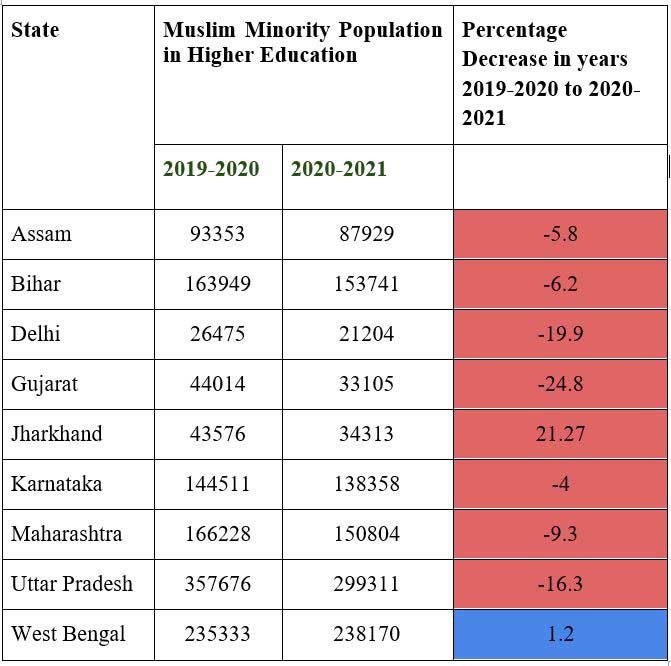

States such as Uttar Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, Bihar, and Karnataka significantly contribute to the decline in Muslim enrolment, with Uttar Pradesh alone accounting for a decrease by 16 per cent and Delhi showing a steep decline of almost 20 per cent. Importantly, the Muslim community is the only category to experience an absolute decline, while other communities have witnessed an overall increase in enrolment.

Figure 1.1 Data source: AISHE-2020-2021

Figure.1.2 Data source: AISHE-2020-2021

States which have witnessed a decline: AISHE 2020-2021.

This decline in Muslim enrolment in higher education raises serious concerns about equal access to education and opportunities for the Muslim minority in India. It underscores the necessity for targeted efforts and policies to address this issue and ensure inclusive and equitable access to education for all communities.

The underrepresentation of Muslims in higher education is a cause for profound concern, considering their low enrolment rate of 4.6%, despite constituting approximately 15% of the population. This marginalisation is indicative of deep-rooted inequalities and challenges faced by the Muslim community. Historically, Muslims have consistently had lower enrolment rates compared to other social, religious, and caste groups, except for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.

While Muslims previously had slightly higher enrolment rates than OBCs, the situation has worsened over time. Dalits surpassed Muslims in terms of educational representation in 2017-18, and in 2020-21, Adivasis also outperformed them. The report further highlights that among major states, Muslims outperform Dalits only in Tamil Nadu, Telangana, and Delhi, while Adivasis perform better than Muslims in states like Rajasthan, Assam, Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Jharkhand.

The ban on wearing hijab in educational institutions in Karnataka sparked a contentious debate in 2021, raising concerns about discrimination and the violation of Muslim women’s rights. According to a report by PUCL-K, approximately 1,010 hijab-wearing girls dropped out of pre-university colleges in Karnataka due to the ban and other factors. The report criticised the sudden prohibition without proper protocols and consideration for the rights of Muslim women students. The timing of the ban during end-of-year examinations further exacerbated its impact.

In the context of affirmative action for Muslims, the Sachar Committee Report (SCR, 2006) identified three states in India that have implemented successful models. In Karnataka, non-Brahmin Hindu castes and non-Hindu minority communities, including Muslims, were declared backward classes. The Nagan Gowda Committee recommended categorising the backward classes into backward and more backward groups, resulting in a reservation magnitude of 68%. The Havanur Commission proposed a separate minority category with reservations not exceeding 6%. In Karnataka, Muslims with an income of less than Rs. 2 lakh were classified as “More Backwards” with a four per cent reservation. This approach led to increased Muslim representation in government services and professional courses such as Medicine, Dental, and Engineering.

Kerala’s positive discrimination policies too, have contributed to the growth in enrolment among Muslims, with the state having the highest percentage of Muslim youth (43%) attending higher education. The reservation system in Kerala allocates 40% for Backward Classes and 10% for Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs), with a separate quota of 12% for Muslims. These policies have played a crucial role in improving educational opportunities for Muslims, as evidenced by the high literacy rate of around 90% among Muslims in Kerala.

In Tamil Nadu, Muslims do not have separate reservation but are included in the backward categories. The state eliminated religious-based reservations, and nearly 95% of Muslims are part of the backward classes. It is worth noting that the current reservation percentage in Tamil Nadu exceeds the limit set by the Supreme Court, standing at 69%.

Bihar’s approach, known as the “Karpuri formula,” involved dividing the backward classes into Other Backward Classes (OBCs) and More Backward Classes (MBCs). Quotas were allocated for OBCs, MBCs, SCs, STs, women, and economically backward individuals.

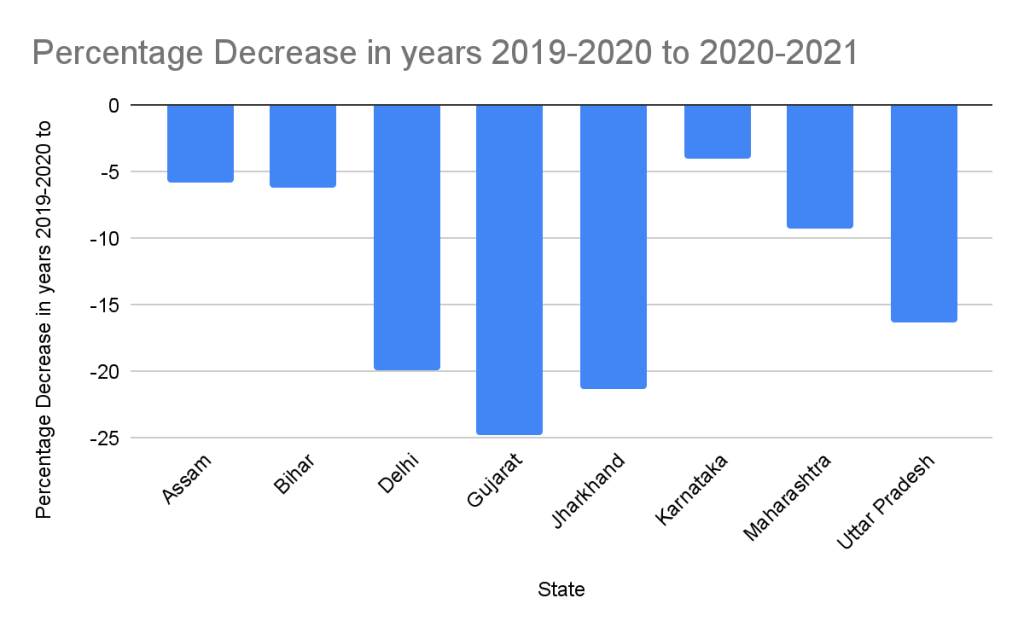

Data Source: https://www.roundtableindia.co.in/general-elections-2019-a-short-comment-on-muslim-representation/

Share of higher and lower caste Muslims in Lok Sabha.

Pasmanda Muslims face socio-economic challenges on a scale worse than almost all other socio-religious categories. They experience economic disadvantages, limited educational opportunities, social discrimination, and political underrepresentation. Efforts should be directed towards improving education, economic empowerment, social inclusion, and political representation to uplift their conditions and promote equality.

The social disadvantages faced by Pasmanda Muslims, categorised by social scientists as Ajlafs, and Arzals, is of significant concern, according to the Sachar and Ranganath Mishra Committees. While some Muslim castes are recognised as OBCs, acquiring scheduled caste status would provide greater government support and legal protection for citizens who fall on the extreme end of the social hierarchy. Data on Dalits and other lower-caste Muslims is scant, but they constitute a significant portion of the Muslim population, according to Pasmanda leaders.

The Sachar Committee Report of 2006 shed light on the social, economic, and educational disparities faced by the Muslim community in India. It identified various obstacles and proposed recommendations to address these issues. The report specifically highlighted the inadequate provision of educational, medical, postal, telecommunication, and basic infrastructure facilities in areas with a high concentration of Muslims. Additionally, it revealed limited access to toilets and difficulties in accessing water for Muslim households compared to the general population. The report also highlighted lower workforce participation.

According to the findings of the Sachar Committee, the enrolment of students from various communities in schools is influenced not only by their household’s economic conditions but also by factors like local development, such as the presence of schools and infrastructure, and the educational background of parents.

There are noticeable disparities at the state level when it comes to the presence of educational facilities and infrastructure in villages with high concentration of Muslims. For instance, West Bengal and Bihar have approximately 1,000 villages each that lack these facilities, while Uttar Pradesh surpasses them with 1,943 such villages. When it comes to housing and hygiene, a smaller proportion of Muslim households live in sturdy houses compared to the overall population, and approximately half of Muslim households in India do not have access to toilets. Moreover, access to amenities like tap water, electricity, and safe drinking water is comparatively lower among Muslims, particularly in villages with a high concentration of Muslim residents, as compared to the national average. (SCR, 2006)

Despite the substantial evidence pointing to the significant deprivation faced by Muslims, Dalits, and Tribals in India, the current government has taken steps to curtail social welfare measures targeting these marginalised communities, particularly in the educational sector. The Union Budget of February 2023 reflects a 38 per cent reduction in funds allocated to minorities, with Muslims being the most educationally disadvantaged among the minority groups. One notable discontinuation is a scheme that provided a modest amount of Rs. 1,000 per year to primary school children from minority backgrounds with an income limit of Rs. 1 lakh per year. This scheme was discontinued for students in grades I to VIII, citing overlap with the Right to Education Act, which guarantees free education until the age of 14. However, this justification overlooks the minimal financial support the scholarship provided and its role in assisting economically disadvantaged students with expenses like textbooks, uniforms, and study materials. Moreover, the Maulana Azad National Fellowship for minority students pursuing PhD programs and the Padho Pardesh scheme, supporting minority students studying abroad through subsidised loans, were abolished. The Minister for Minority Affairs, Smriti Irani, has provided explanations for these discontinuations, but they fail to address the actual challenges faced by students. The underlying motive behind the elimination of these programs is not a mystery; the ruling BJP party has consistently criticised these schemes as “discriminatory” since their initiation under the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government following the 2006 Sachar Committee report, which exposed the alarming educational disparities faced by Muslims.

It is worth noting that the Gujarat High Court intervened in 2013, compelling the Narendra Modi-led government in Gujarat to implement a prematric scholarship scheme for minorities after a public interest litigation (PIL) argued that the scheme violated the constitution by being based on religious grounds. This historical context sheds light on the challenges and controversies surrounding these welfare measures.

The Sachar Committee Report revealed that Muslims, especially women, face significant barriers to accessing government development programs, leading to discrimination and exclusion. They encounter difficulties in obtaining loans, housing assistance, and pensions, and often struggle to obtain caste certificates, hindering their eligibility for reservation policies. The challenges extend to acquiring ration cards, preventing them from accessing state services and educational benefits. The segregation of Muslim communities further exacerbates these issues, limiting their access to essential services and government institutions. Additionally, Muslim women face underrepresentation in decision-making roles and exclusion from minority welfare institutions, impeding their full participation in society and the opportunities provided by government initiatives.

The issues of declining Muslim enrolment in higher education, the ban on hijab in Karnataka, and the challenges faced by Muslims, Dalits, and Adivasis require urgent attention and comprehensive policies to promote inclusive education, address socio-economic disparities, and ensure equal opportunities for all. Efforts should be made to provide targeted support to marginalised communities and remove barriers to their educational and professional advancement. Furthermore, promoting social inclusion, economic empowerment, and political representation are crucial steps toward achieving true equality and justice in Indian society.

Related

Does the State have the right to disrupt Muslim woman’s right to education?

Jamia student leader, Masud Ahmed, gets bail in ED case, to remain in jail in Hathras UAPA case

Haleema Beevi: Pioneer of Social Reform and Broad-Based Muslim Education in Kerala