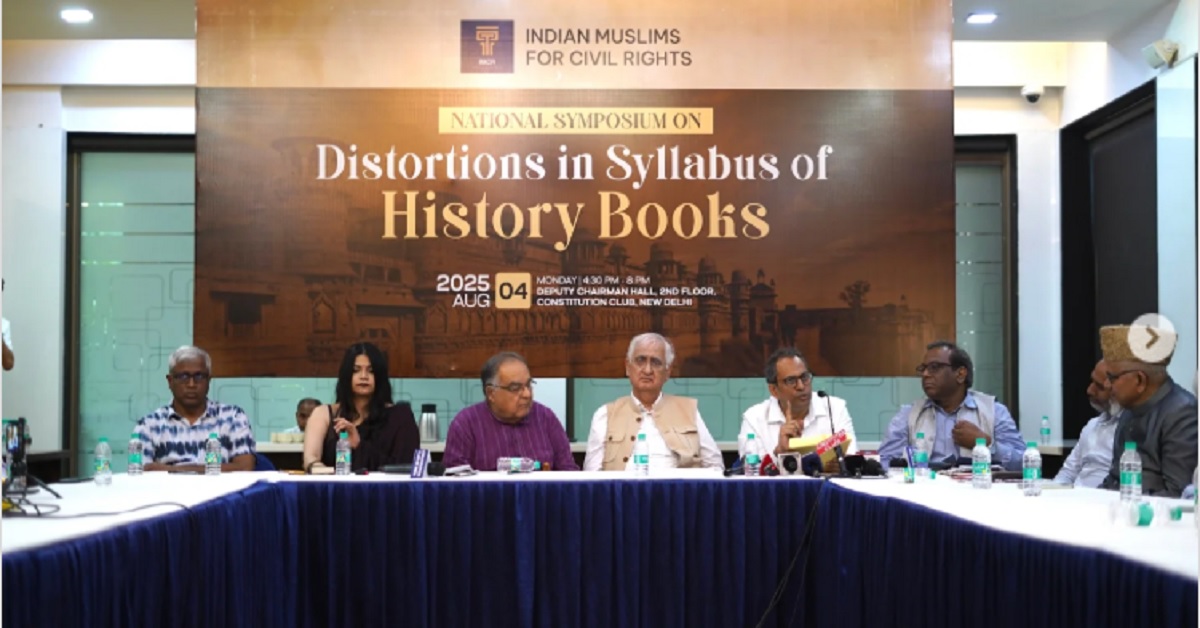

The Indian Muslims for Civil Rights, Salman Khurshid sahab, Mohd Adeeb sahab, Ashok Kumar Pandey Ji, Ashutosh Kumar Ji and the valiant, feisty, combative young historian Dr Ruchika Sharma. In this battle of ideas, the knowledge of history has also to be disseminated on visual and other forms of media and communication.

I am nervous in speaking before this panel of knowledge elites who are far ahead of me in mediatized performance. In fact, I was hardly needed within this panel, given there is a galaxy of experts present.

These days, communicating within (and among) the like-minded audience is hardly a challenge and it doesn’t serve the desired purpose as much as it should. The panellists have already spoken a lot on the theme of the symposium. At stake are the words, “evidence”, “proof”, “facts” (subut, sakshya, pramaan). The incumbent regime is doing everything in its power to create a common sense against “evidence” (rationality). Not just in the discipline of history but in every sphere of our daily lives. Not just in India; elsewhere too. Non-state actors, with the backing of state power and wilfully failed criminal-justice system, are deciding what we eat, what not to and what kind of edibles can be stored in our kitchens and refrigerators. These factors impinge on whether we can live or can be killed with impunity.

We are here to reflect upon the National Education Policy 2020. Its basis, as admitted by the Indian government is National Curriculum Framework for School Education 2023. The three year of school education during the Grades 6 to 8, according to them are very critical. They do admit that content and pedagogy both are crucial. I looked into the textbooks meant for Grade 6 and for Grade 7. The title is Exploring Society, India and Beyond. The regime claims that these textbooks have an emphasis: minimizing the text by focusing on core concepts. “Focusing on big ideas”, is their emphasis in the “Letter to the Student”, appended at the beginning of the books; and multi-disciplinary approach is an important stated concern. Fundamental Rights and Duties are excerpted from the Constitution, and printed with embellishment. All these are high sounding claims, apparently. But not so, as we get into the details by proceeding further into the book.

A few years ago, we also had “Learning Outcomes based Curriculum Framework (LOCF): BA History Undergraduate Programme, 2021”. In an essay in the journal, Social Scientist, Irfan Habib has written extensively. The prose is endearingly satirical, a trait which the eminent historian employs in his public speaking and less in writing and within the classroom. I would strongly recommend that all of you read the essay. Such a Framework from the regime envisages political encroachment upon the curricula-framing and through this the shrinking autonomy of the universities.

Maulana Azad’s role as education minister (1946-58), along with Nehru and Radhakrishnan, in the autonomy of the UGC was foundational (1953-56). He championed the creation of an independent statutory body to manage and fund higher education, a move that was essential for the institutional autonomy of universities and for the development of a standardized and high-quality higher education system in India. Not only this, Maulana Azad served as the Chairman of the Central Advisory Board of Education (CABE), a vital body for advising the central and state governments on educational matters and in framing school curricula. He presided over multiple meetings of the board, including those held in 1948, 1949, and 1950. This position gave him a direct platform to shape and influence educational reforms and policies at a national level.

Maulana Azad was quite conscious of the fact that the Medieval historical past (Muslim rulers) will be weaponized in certain ways by both, Hindu and Muslim communal forces. He therefore instructed (1949) ‘the historians of AMU to conduct research on that period by accessing original sources in Oriental languages.’ While resisting colonialism, his own perception of the Mughal past was distinctive. For instance, he looked upon Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi’s resistance (otherwise quite a conservative figure) against Akbar as an instance of why Muslim subjects too rise in resistance against the British colonial state (See Muzaffar Alam, “Maulana Azad and his memory of the Islamic past: a study of his early writings”, JRAS, Cambridge. 33, 4, 2023, pp 901-916)

For the diminishing autonomy of the universities in recent decades, politics is responsible as also the misuse and abuse of autonomy by the universities and the academia themselves, over a period of time. Recently, the Vice Chancellor (VC) of a prestigious university recently got a show cause notice on the flimsiest of grounds and the notice was not issued by the Visitor. More on that on another occasion!

The specific theme around which we have gathered here is something we are agitated about given that the incumbent regime is selective about facts, besides distorting the facts of history and more than that, which is, not less important, manipulating historical facts in most insidious ways. Manufacturing falsehood, parading these as history, and thereby poisoning the minds of children, of ordinary people in general. That is our concern here. There is a systematic attack on reason. People should not have minds, apply them, should not have or develop any critical faculty. They should not be thinking like citizens with powers of critical thinking, rather, they should function as mere subjects, praja, reáaya, before rulers. This appears to be the dominant political wisdom today.

We also need to keep in mind the fact that the NCERT textbooks are written more for the purpose of teaching material to the teachers. This is the purpose forgotten a long while ago.

Just four days ago, my teacher, Prof Farhat Hasan, along with Prof. Neeladri Bhattacharya, in their interview with Vrinda Gopinath (The Wire.In, July 31, 2025), have articulated all the important concerns pertaining to the issue. Ruchika has been doing it consistently in so many ways with effective communication. I hardly need to repeat these here. I would therefore seek your permission to raise some other issues which may not be getting adequate attention in terms of diagnosing the trouble. Just for the sake of informing the less informed, non-specialist audience here, allow me to do a quick recap, before embarking on the issues I wish to raise here:

In the latest version of NCERT textbooks, we have:

- Demonisation of Mughal rulers including Akbar (a feat achieved by Muslim reactionaries too); and the controversy around Aurangzeb-Shivaji. Through both of these, we can clearly identify the ways in which Hindu and Muslim Right Wing treat history.

- Discussing historical periods and rulers within the binaries of ‘Glorious’ and ‘Dark’ periods and rulers defined as ‘Heroes’ and ‘Villains’, in terms of their personal faith. This irrational method overlooks overall state policies and political contexts and values of the era, and thereby creates an atmosphere through which co-religionists of these past rulers are made answerable for certain deeds. Taken to extremes, this can mean ‘punishing them for the previous wrongdoers.’

- The authors/editors of the NCERT textbooks of the 1970s and then again in 2005-06 had reputed professional academic historians this is not the case anymore;

- Earlier, each chronological period had judiciously distributed adequate space, across the evolving grades from VI to XII;

- All regions had spaces in terms of history-making, in the earlier textbooks, yet there were allegations of selective emphasis;

- Gender, Caste, Environment, Technology and Socio-economic changes, Growth of Science in history, sports, literature, sartorial culture, etc., were the issues which remained less addressed; with the evolution of a historical understanding, these issues were attempted in the NCET textbooks of 2005-06. Yet, right wing allegations persisted.

- Allegations of the Right wing were and are (about earlier books), temple ‘destructions’ during the time when Muslim rulers ruled were not emphasized in these texts. Making this argument they pushed for deletion of similar acts by Hindu rulers. Narratives built to create a communally divisive atmosphere. As if today’s ordinary Muslims are answerable for the past conduct of Muslim rulers, and today’s Hindus aren’t answerable for the similar acts of the Hindu rulers in the past.

- Anglo-Maratha Wars are okay to be taught, the Anglo-Mysore wars must to be omitted

- Ironically, while right wing forces might apparently talk of nativism laced with the rhetoric of being anti-West, at the same time their historical narratives derive much from the colonially divisive projects of historical representation; Dr Ruchika Sharma is doing a lot to speak and write on these.

History has a political goal, has been a tool of ruling class, across the globe. It was so, always. This reminds me of Paul Freire’s 1968 book, Pedagogy of the Oppressed. He identifies two objectives of pedagogy: a tool for domination, and a tool for liberation. Here there are two models viz., “Banking Model”, in which the students are treated as passive recipients who in turn become unthinking, “submissively obedient” and status-quoist.[1] This de-humanises both the teachers and the students. In this, the oppressed turn into a new batch oppressors. Another model of pedagogy, Friere says, is: “Problem-Posing Model” wherein the teachers and students are co-educators to each other, it is dialogic and interactive.

In this context, one is also reminded of a recent book, Hilary Falb Kalisman, Teachers as State-builders[2]. This book talks of teaching which turns students into a force of resistance, state-subverters, disruptors, challengers to the status quo, and thereby creating thinking citizens who will build stronger society and state, rather than collaborators of the regime. That is how, Kalisman says, colonial societies emerged to resist the state and attain freedom.

School textbooks are often used to both craft what the nation is or must be and to “teach” future citizens how they are now bound to and by a common historical narrative. Therefore, it is not surprising that India and Pakistan (and later Bangladesh) have put concerted efforts into crafting propaganda-like historical narrations about what their nations stood for.

Such historical narrations ‘droned on, ponderously, sonorously, and repetitively’ in citizenship projects about how the nation came to be formed and what the nation-state did for people’s benefit. Joya Chatterji (in her Shadows at Noon, p. 145) writes: ‘It was not so much that this publicity was executed with brilliance. It was not. It was merely the case that it was repeated ad nauseam, and that everydayness made the message natural’.

Not that history has not been used as a tool in earlier times! But then it was, as it should be, used as a tool of emancipation. Emancipation of the colonised, enslaved people. To inject self-confidence among the rising nation, the nation in making. By the word, nation, I mean people, not merely territory. Jawaharlal Nehru’s Discovery and Glimpses were written for those noble purposes. Tara Chand’s books, the books written on the history of 1857 in 1907-09, in 1957, in 2007, etc., by the scholar-activist nationalists were pursuits in those directions. The NCERT textbooks, the books written for popular readings and published by the NBT were all exercises in those noble desirable purposes and directions.

Modern rational, secular democracies need such pursuits immeasurably. Praja ko Nagrik mein badalna hai, that is our biggest challenge today. It is a battle between “communalisation” and “secularization”. Please do note the difference. I am not using the words, “communalism” and “secularism”. I am using its variants, the process, not the mere nouns.

Once we read, Yasmin Khan’s 2011 essay (Modern Asian Studies), “Performing Peace: Gandhi’s Assassination as a Critical Moment in the Consolidation of the Nehruvian State”, we get to know, beyond the stated motive of the author, that the Nehru-led state was making efforts which were, in turn, using it in a certain way; the way for the marginalizing the forces who liquidated Gandhi’s body and life, if not his mind and ideas and ideology and praxis and methodologies. Nehru strategically managed the public mourning, funeral, and distribution of Gandhi’s ashes to assert state power and legitimise Congress leadership during the turbulent post-Partition period (1947–1950). The state-organised funeral in Delhi, contrasted with widespread, vernacular mourning rituals across India, bridged the gap between the state and the people, reinforcing Nehruvian secularism. Public grief, amplified by events like the Ardh Kumbh Mela, transformed Gandhi into a saintly figure, fostering communal harmony and countering Hindu nationalist sentiments. Yasmin Khan emphasizes that these rituals were not merely ceremonial but politically transformative, solidifying the Congress Party’s role in shaping a unified, secular Indian state.

Nehru was very clear about the problem of communalism. He knew it more clearly than anybody else that in colonial era Muslim communal separatism was stronger because of the colonial state; during 1938-47, competitive communalisms of the two largest religious communities became greater menace because of the colonial state. After 1947, more particularly, after January 30, 1948, Hindu communalism was greater threat. Patel realised it only after January 30, though he didn’t survive for long after that to help Nehru in a larger way. He died in December 1950; not in 1960 (our Home Minister, Mr Shah should allow me to correct him)!

I was referring to the processes of communalisation. These forces remained there, not exactly subterranean, in the early years of independence. The majoritarian forces were apparently and arguably not in a hurry to be state-centric. They were working more on cultural fronts, and in the spheres of education, with the “Catch-them-Young” approach. This focus was there among both Hindu and Muslim communal forces. Both, were waiting for the right moment to capture state power for a full scale implementation of their communalisation programmes. In Pakistan, this project was hardly ever in resistance, as the very basis of the creation of Pakistan was communal. Krishna Kumar and at least in a column, Arvind N Das had written extensively on this. Persons, some previously with the prestigious, St Stephen’s, [I H Qureshi (1903-1981) and also the Gen Zia’s regime] did much to push Pakistan rightward. Ali Usman Qasmi’s (essay in Modern Asian Studies, 2018), “A Master Narrative for the History of Pakistan: Tracing the origins of an ideological agenda”, explains this phenomenon at length.

Gen Zia’s reign (1977-1988), more aptly depicted in Hanif’s novel, A Case of Exploding Mangoes[3], coincided with the Saudi-funded project of the Islamisation of Knowledge (IoK) scheme. A range of scholars in different parts of the world started promoting Islamisation of Knowledge (known as ‘IoK’) in the late 1970s. The first World Conference on Education in Makkah (1977) marked a decisive step in the formulation of this project on an international platform. [Among the best-known scholars advocating this notion were Palestinian–American scholar Ismail al-Faruqi and Malaysian philosopher Syed Naqib al-Attas. For radicalization under Gen Zia’s regime, see, Virinder and Waqas Bhatt’s ‘If I Speak, They Will Kill Me, to Remain Silent Is to Die’: Poetry of resistance in General Zia’s Pakistan (1977–88), Modern Asian Studies, 53, 4, 2019. Also see my blog, “Namo’s India a parody of Zia’s oppressive regime in Pakistan?”, SabrangIndia. In, February 17, 2020].

“Sub-continental Majoritarianisms”, to use Papiya Ghosh’s expression, and global politics of the Ummah created a fear among Hindus, especially after the Khilafat mobilisations during the national movement. After Partition too, Hindu Majoritarianism derived fodder from such political pursuits of the Ummah. (Sir Syed Ahmad Khan was against the pan-Islamic, extraterritorial, Ummah; he was for a Qaum confined within national boundary). This phenomenon (Muslim communalism) feeding majority communalism has been afoot since the 1970s and 1980s. This is not a marginal factor. One communalism feeds another, is what Nehru had said, and Bipan Chandra later elaborated upon it.

India and its own Muslim right wing organizations were not averse to or unconnected with the abovementioned schemes promoting the Muslim right wing. Please do have a look into Chapter 6 of Laurence Gautier’s latest book on post-1947 AMU and JMI, Between Nation and Community, Syed Anwar Ali, a Jamaat-e-Islami affiliated teacher in the AMU and his book, Hindustan Mein Islam, and I H Quraishi’s book, The Muslim Community of the Indo-Pakistan Subcontinent, 610-1947, which give us a clear idea of Muslim Right Wing in our sub-continent, pre and post-1947.

All right wing forces have globalised networks. Secular resistance too has to ensure globalised networks of solidarity. No study or commentary in isolation will really help us understand the communal forces. (Communalisation of the textbooks is just a part of that politics); and thus, a less informed understanding and flawed or partisan diagnosis will not help us create an effective solidarity. Going soft on the Muslim right wing and hard against the Hindu right wing has proved a counterproductive strategy all these years.

Khoo gar-e- Hamd se thorha sa gila bhi sun le

Barring one or two lesser known pamphlets published by the Indian Left I have hardly come across any comprehensive criticism against the India’s Muslim right wing pursuits in these domains. We do understand that post-1947, the Muslim Right Wing couldn’t be as dangerous as the Hindu Right Wing. It was Nehru’s understanding of communalism and it was his desired magnanimity. That does not, however, really mean that such a lesser danger would not attract attention and will not be resisted. I am not compartmentalising the resistances we ought to offer.

Given the contemporary challenges, I strongly feel that Muslim intellectuals (if they really exist) of India need to speak out more on those aspects. India’s Liberals as also Leftists have reasons to agree with Nehru’s understanding on the colonial and post-Independence communalisms in India (Nehru understood that Muslim communal separatism was more dangerous only till 1947, under the colonial prodding; post-1947 India, Hindu communalism is more dangerous). To this, Late Prof Imtiaz Ahmad had an opinion: this differential understanding doesn’t really mean that while fighting the two communalisms you will discriminate between the two. They have reasons not to speak as much on Muslim right wing. But that cannot be a choice for the Muslim intellectuals. The more they avoid exposing India’s Muslim right wing, the more they provide weapons to the Hindu right and the more they weaken the moral authority of India’s Secularists.

I am only reminding this audience of the fact that minority rights discourses from Muslim leaders have remained weaker during our national movement (the Muslim League shifted this discourse to a direction in which Muslim minority was to be treated to be a nation of ex-rulers), and after Independence too, communal-identitarian concerns were given priority. Rather than strengthening the secularisation processes of India, Muslim intellectuals have remained more active in safeguarding regressive and patriarchal Personal Laws, and less at strengthening the secular forces of India. The religious and “secular” Muslim leadership has remained more identitarian, less secularistic. That has all along done a great disservice to the overall processes of secularisation, only to help majoritarian forces.

Fast forward to 1977 and after: Resurgence of competitive communalisms in the 1980s

Riding on alliance-politics, majoritarian forces in India eventually succeeded, more menacingly with the turn of this century/millennium. They had never really given up. Competitive majoritarianism remained a force to reckon with across the sub-continent. Whenever they formed governments in alliance/coalition in New Delhi, majoritarian parties preferred to the portfolios education, culture, information and broadcasting. Other non-Congress or anti-Congress regional forces hardly pitched for such portfolios.

Unlike majoritarian parties, secular forces, most of who have been state-centric; were dependent upon state resources, subsidy concessions and spaces to run their secularisation projects. Of course, the Left forces existed in industrial trade unions, on the university campuses, students and youth movements, and in the peasant movements, and through certain effected cultural organisations in both theatre, literature and art, too. A changing global economy and the disintegration of the USSR has weakened Left forces in recent decades.

One of the reasons why in recent years more and more Hindus have embraced Neo-Hindutva is the real question to be addressed, here. To my understanding, this question is fundamental because the attack on rationality and ever-increasing receptivity of the falsehood and of the distorted history is linked with this issue. This leads us to another question, how did we deal with the Muslim communalism, in the colonial era as well as in post-independence era?

What proportion of the Muslim literati looked at India’s ancient past with desirable and reasonable pride? Why did Shibli feel more agitated to write in defence of Aurangzeb? Why did he write biographies only of Muslims – non-Indian, Arab-Muslims at that? What proportion of Muslim elites are self-critical? To what extent do they look critically upon the ideas, institutions and history-making individuals of Muslims? What made a section of Muslim elites run a narrative of venerating Aurangzeb as Zinda Pir, and adding the suffix of rahmatullah alaih too?

An honest answer to those questions may help us find one of the missing answers for the first question I raised here as to why more and more Hindus have been embracing majoritarianism in recent decades.

The vilification and/or “villainisation” of Medieval Muslim rulers by Hindu majoritarian and reactionary forces, by stating half-truths, or putting out facts in a distorted manners, is just one problem! What is the obverse side of this problem? Why do a section of Muslims of today feel so very compelled to defend and justify and eulogize only a certain kind of Muslim rulers? Omission of the story of valiant resistance and confrontation of British colonialism by Tipu Sultan is an obvious problem. The latest NCERT edition has omitted Tipu. A valid resistance to this politics does require that certain facts about Hyder-Tipu rule should not be ignored or omitted by secularists too. The Moplah-Nair “communal” conflict has an agrarian history of land ownership as to whose ownership preceded whose, before and after Hyder-Tipu rule? D N Dhanagre (Past and Present, OUP, vol. 74, 1977) has written about this. Quite a secular historian. Yet, that fact, uncomfortable for Muslims and Liberals and Left, has been obviously overlooked. Ignoring these aspects of history not just makes us intellectually dishonest, it also thereby weakens the legitimacy of our resistance. And that is how we self-restrict building a solidarity for our cause. We have to rethink and introspect.

I recall having read a long interview of Intezar Husain, with Umar Memon (July 1974), published in the early 1970s. (English rendering carried in the Journal of South Asian Literature, 1983). Intezar reminded us Muslims that, in comparison with the Hindus, our attitudes vary. This variation hasn’t been addressed as adequately as required. That has contributed to communalisation and pushing the country rightward.

Our discriminatory and dishonest treatment of both communalisms might be one of the factors why Hindutva has been gaining greater acceptance among growing number of Hindus?

I would therefore seek your permission to make you a bit uncomfortable at least in the last segment of this talk, if not intermittently throughout the talk.

Intezar argued that Shibli Nomani “continually romanticised our history, but there were some other aspects of our history which he didn’t describe at all”. Nirad Chaudhuri’s Continent of Circe, “dealt with the history of India and analysed the Hindu community in an uncompromising and even brutal manner”. “The Muslim community has taken great pride in the fact that the philosophy of history was born among Muslims. But the fact is that these Muslims do not face their history squarely, but merely picked out its good features and then celebrated these as the entire whole of our history. Nirad Chaudhuri’s approach is completely the opposite since he has no wish to “celebrate” the history of the nation of which he is one individual. We see him striving to reach its essence and to present that essence without regard to how his own people would react to it”, argued Intezar Husain.

Now, my question is this: why when such issues were raised in the 1970s, did they remain unaddressed (or inadequately) addressed as before? Addressing these questions may help us understand, at least partly, why more and more Hindus have begun to hate Muslims incrementally.

I have already referred to Syed Anwar Ali’s Urdu book Hindustan Mein Islam. This could be a case study to measure the Muslim right wing’s way of looking at post-Independent Indian History (and their political intent too) Anwar was a faculty at AMU.

As the Hindu right wing has engaged more in vilifying Muslim rulers in general, they appear to be less interested with the Muslim right wing’s knowledge production in India. The day they take this up, things would become even more difficult in terms of building solidarity and resistance against Neo-Hindutva.

Leaving this at that, let us come around the issue of Partition. The subject has been taught through the prism of causes, not on consequences. Why? Because, causation is motivated with the idea of blaming someone and absolving others. In this case, since the League asked for Pakistan and got it, it has to share greater blame. Nonetheless, in such a restricted or selective teaching of the causes behind Partition, Muslims and Muslim League are hardly distinguished from each other, even in among some of liberal circles.

Why is it that stories and narratives of Muslim resistance to Partition remain under-explored, under-prescribed and under-popularised? Why do a good number of educated Muslims of India still rejoice in a historical literature which absolves Jinnah and his League? I leave this question for certain sections of the Muslim educated elite of India: to undertake an honest self-introspection on this count too.

Following two works of Muslim writers are very significant in the genre of anti-League Partition literature.

Syed Tufail Ahmad Manglori’s 1946 book, Musalmanon Ka Raushan Mustaqbil, got translated into English in 1994 only. Similar literature, such as Hifzur Rahman Seohaarvi’s 1945 book, Tehreek-e-Pakistan Par Ek Nazar, remain least known. Does this mean that in academic circles as well as in the popular domain, anti-League Muslims remain lesser known? How many of the Muslim literati really talk about such figures and such writing? I have spent over three decades as student and as teacher in AMU. Few years back, when I was addressing an AMU gathering, on Tufail Manglori (Manglauri), the founder of the City School and shared that he was an ace wicket keeper of the MAO College Cricket team, the information was received by a large audience with surprise. Very few knew about this. A good number of Muslims do remember Seohaarvi as an ex-MP but his anti-League book, Tehreek-e-Pakistan is hardly known even among the literati or the chatterati.

Mushir-ul-Haq (1933-1990) has demonstrated it very well in his 1972 essay, “Secularism? No; Secular State? Well- Yes”. In this essay Haq highlighted a contradiction in the approach of some Muslim leaders. He observed that while they might publicly criticise “secularism” as a concept, they would simultaneously defend the “secular state” and the constitutional protections it afforded them, such as minority rights and the freedom to manage their own religious and educational institutions. He pointed out that this stance could appear to be a form of double standards.

With this, the point I am trying to emphasise here is: in order to strengthen the fight against Neo- Hindutva and in order to strengthen the hands of the likes of Yogendra Yadavas, Apoorvanands, Harsh Manders, Ravish Kumars, Ruchika Sharmas, we ought to resolve that critiquing and exposing the Muslim right wing should not be the business best ignored by thought-leaders, opinion-writers, academics, public intellectuals bearing Muslim names. They must not shy away from this urgent task. They must not keep arguing to the tune that ‘this is not the right time for burdening Muslims of India’ with such a task. For too long we have made such a fallacious and counterproductive argument. This is one of the many factors having contributed to the rise of Neo-Hindutva. The projects of communalising the textbooks, the state and the society have been gaining strength with the way we have been arguing, “this is not the right time to critique, expose and resist the Muslim conservatives and right wing ……’

Do we really even realise the depth of the threat?

I am very sorry to say the answer to this question is not in the affirmative. I am saying this with the unique experience of working with and living on a Muslim majority campus. This is a pessimism coming from me who in his own self-assessment is not someone who gives up on anything easily.

Before I leave, I must clarify what Neo Hindutva is:

The term “Neo-Hindutva” is a relatively recent academic and journalistic concept used to describe the evolution and new expressions of Hindu nationalism in contemporary India, popularised by scholars such as Edward Anderson and Arkotong Longkumer in a 2018 special issue of the journal Contemporary South Asia and an earlier 2015 article, which is, “idiosyncratic expressions of Hindu nationalism which operate outside of the institutional and ideological framework of the Sangh Parivar”, quite distinct from the modernisation of Hinduism by figures like Swami Vivekananda in the late 19th century.

Neo-Hindutva is defined as a more diffused, mainstreamed, and adaptable version of traditional Hindutva. Unlike the original ideology formulated by Vinayak Damodar Savarkar in 1923, which was explicitly a political theory of Hindu nationhood, Neo-Hindutva is characterised by its ability to permeate new spaces and take on various forms.

Key characteristics that distinguish Neo-Hindutva from its traditional counterpart include:

- Mainstreaming and Normalisation: It is no longer confined to the institutional and ideological boundaries of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and its affiliates (the Sangh Parivar). Instead, it has become a normalised, everyday discourse that is seen in popular culture, social media, and even in spaces like yoga and spiritual movements.

- Focus on Development and Neoliberalism: Unlike traditional Hindutva, which was often viewed as separate from economic policy, Neo-Hindutva has been linked to a specific brand of neo-liberalism. It often frames economic progress and material prosperity as a result of and a prerequisite for Hindu assertion. This ties national pride and economic growth together.

- “Hard” vs. “Soft” Expressions: Scholars like Anderson categorize Neo-Hindutva into two types: Hard Neo-Hindutva: This includes groups and movements that are openly connected to Hindu nationalism but operate outside the direct control of the Sangh Parivar, often with a more militant or vigilante approach. Soft Neo-Hindutva: This is a more subtle and concealed form, often avoiding explicit links to majoritarian politics. It operates through think tanks, international organisations, and cultural groups that promote a Hindu identity and narrative under the guise of cultural preservation, charity, or community building.

- Appeal to new constituencies: Neo-Hindutva has expanded its appeal beyond the traditional upper-caste support base by incorporating and co-opting the aspirations of lower-caste groups and Adivasi (tribal) communities, often by offering them a space within a broader, unified Hindu identity.

Thank you for the patience in listening to my discomfiting words!

(The author presented this view on August 4, 2025 at a symposium held at the Constitution Club of India, New Delhi, topic Distortions in the Syllabus of History Books; the presentation sent to us by the author has been suitably edited for publication)

[1] Brazilian educator, Paulo Freire written in Portuguese between 1967 and 1968.

[2] Assistant Professor of History and Endowed Professor of Israel/Palestine in the Program for Jewish Studies at the University of Colorado Boulder

[3] 2008 comic novel by the Pakistani writer Mohammed Hanif. It is based on the 1988 aircraft crash that killed Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, the sixth president of Pakistan.