“Democracy is more likely to develop and endure when all segments of a society are free to participate and influence political outcomes without suffering bias or reprisal.”

There has been much ado regarding the Muslim vote. What of the Muslim parliamentarian? A recent report by The Hindu reveals that there are no elected Muslim Ministers of Parliament in areas that have a high concentration of Muslims.

As reported by SabrangIndia, a paper by the think tank Hindu Centre for Politics and Public Policy written by Gilles Vernier notes that there are 34 out of 80 Lok Sabha constituencies and 130 out of 403 assembly constituencies where the Muslim population is of considerable strength in number.

Furthermore, according to the report by The Hindu, the presence of Muslim MPs is inversely proportionate to the presence of BJP MPs. Interestingly the report also notes that the share of Muslim MP’s from the Indian National Congress has also declined by 7.5 % from its peak in the year in the sixth, seventh and eighth Lok Sabha, years 1977-1989. These were the Janata Party ruled coalition years, ironically.Given that the traditional support base of the grand old party spanned across privileged sections and also inspired support from marginalised sections, both Dalits and Muslims, this decline is telling: it speaks of a representation crisis not just of the Muslim community in general but of marginalised sections with the minority Muslims –Pasmanda including Dalits and women too – in particular. The onslaught of an aggressive, autocratic majoritarian Hindutva in the face of the Modi 1.0 and 2.0 regimes has seen the “secular” parties also on a defensive backfoot when it comes to fair representation of all sections including Muslims.

The Hindu reports that the regional parties instead were able to ensure some level of representation for Muslim MPs, for example the Indian Union Muslim League (IUML), Jammu and Kashmir National Conference, Samajwadi Party etc. In addition, CPI-M was also able to fill the gap by giving Muslim representation in both Kerala and West Bengal.

The report also notes that big states such as Maharashtra, Gujarat, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh have also seen a decline in the number of Muslim MPs. Worse, Gujarat, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh do not have a single Muslim MP.

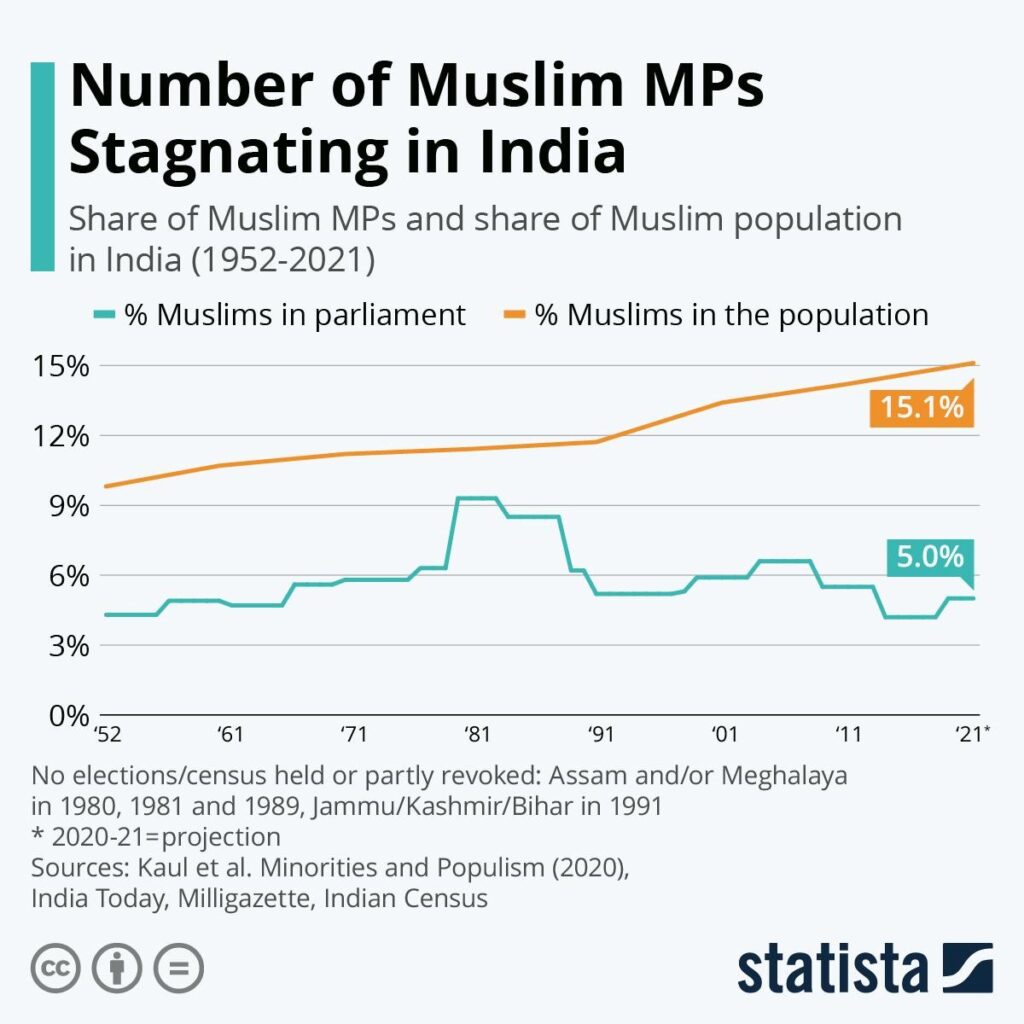

In the 1980s the share of Muslim MPs was at its peak, at about 8.3 % in the seventh and eighth Lok Sabha. Overall, the number of MPs has declined to 5 percent in the last 3 Lok Sabhas in the UPA 1, NDA 1, and NDA 2, and is noted to be similar to what was recorded in the 1990s, which The Hindu report further notes, was also a period which saw the rise of the BJP. However, in the 2000s, after the decline the share went back to 7 % percent with the UPA 1 government, according to The Hindu.

How does the voting pattern work in Muslim dominated areas?

According to a detailed analysis in Sabrang India, during the period from 1991 to 2002, the BJP under the influence of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), experienced electoral success in the state of Uttar Pradesh, largely on account of its polarising Ram Mandir politics after the demolition of the Babri Masjid (December 6, 1992). In 1991,with the stigma and hate-driven campaign for the Ram Mandir at its peak, the BJP emerged victorious in 76 out of 122 minority-dominated seats in UP, surpassing both the Congress (which won only seven seats) and the Samajwadi Party (which won one seat). Interestingly, independent candidates secured the second highest number of seats.

In 1993, the BJP once again dominated the minority-dominated seats, winning 69 out of 122, while the Samajwadi Party won 31 seats, the Bahujan Samaj Party secured five, and the Congress managed to win only six. The remaining 16 seats were won by other political parties or independent candidates.

In the 1996 elections, although the BJP’s overall performance declined, it still secured a majority of the minority-dominated seats by winning 59 out of 128. The Samajwadi Party followed with 43 seats, the Bahujan Samaj Party with 13 seats, and the Congress with only seven.

However, in 2002, the Samajwadi Party under the leadership of Mulayam Singh Yadav gained ground in the minority-dominated seats, winning 43 out of 129. The Bahujan Samaj Party secured 24 seats, while the BJP managed to win 32 seats in these areas. The fact that even at its worst, it still managed a hold on close to 15 per cent of the minority-dominated seats is telling.

Sabrang India’s analysis reveals the stark observation that voting patterns attest the Muslim vote may be a decisive factor in winning a candidate, however if the Muslim vote gets divided between candidates, then each time tha thas happened, it has resulted in the victory of BJP as illustrated above.

A slightly divergent and nuanced trend from poor representation of Muslim representatives in the state assemblies and Parliament is the seats given to the minority community at the local levels (that is Panchayats and Zilla Parishads)

This is true of both of the Model Hindu Rashtra states, first Gujarat, then Uttar Pradesh.

Such astute dual messaging by a party and ideology that is also associated with the stigmatisation and demonisation of Muslims works towards containing the political antipathy of minorities as a block and engaging at least a small section, some families even so that some are drawn albeit at the local levels to a party that is otherwise perceived to be and is detrimental to their social, political and economic interests. The messaging is almost to say that representation benefits them locally but not at the policy making and national levels.

The BJP’ Effect

In India, the total number of seats in the Parliament and state and Union Territory assemblies is 4,908. The Lok Sabha consists of 543 seats, the Rajya Sabha has 245 seats, and the remaining 4,120 seats are allocated to the legislative bodies of the states and Union Territories.

Over time, the representation of Muslim Members of Parliament (MPs) in India’s Lok Sabha has fluctuated. Initially, it increased from 4.3 percent in 1952 to 9.3 percent in 1977. However, it subsequently dropped back to levels comparable to the 1950s and 1960s. Following the 2019 elections, Muslims constituted 5 percent of Indian MPs, despite comprising approximately 14 percent of the population. In contrast, the Lok Sabha is predominantly Hindu, with over 90 percent Hindu MPs, while Hindus make up around 80 percent of the Indian population.

The electoral victory of the BJP, which designates Hindu nationalism as its ideal, has had a dire impact on India’s religious minorities. Although one Muslim MP was elected for the BJP in 2019, the situation for Muslims in India has deteriorated significantly in all areas of life since the party’s rise. BJP’s term has been strewn with lynchings of Muslims, fund cuts for all minorities, shielding or inaction against rape accused members of their party, and heightened state repression for all citizens.

Among states with over 15 percent Muslims, Kerala, Assam, West Bengal, Jammu & Kashmir have largely maintained a consistent number of Muslims MPs over time. Actual numbers? Can we tally these to the party in power at the time? The two exceptions to this criterion is Jharkhand and Uttar Pradesh. In Jharkhand only 1 Muslim MP was elected and in UP, where at its peak there were about 18 percent Muslims MPs, now it has dropped down to 1 percent.

In 2022, the Al Jazeera reported that for the very first time in India’s history as an independent nation, there wasn’t a single Muslim MP from the ruling party to represent a population of religious minorities that forms up to about 14 percent of the nation. BJP’s last long standing Muslim MP, Mukhtar Abbas Naqvi, had recently resigned from his post as Minority Affairs Minister as his term was slated to end.

According to acclaimed social scientists, Christopher Jaffrelot “Between 1980 and 2014, the number of Muslim MPs in the lower house of the Indian parliament – and hence their percentage – diminished by more than half. This evolution is all the more significant as the share of Muslims in the Indian population rose during the same period.”

Image: Statista

BJP and Muslim Women

The BJP has often claimed they have the confidence of Muslim women. Maintaining that the highly contested Triple Talaq Bill was a huge ‘victory’ for Muslim women, the party has often argues after elections that Muslim women votes for them en masse. But even if that were the case, what has the representation of Muslim women been in the parliament?

According to a report by IndiaSpend, Muslim women in India face a double burden of discrimination as both women and Muslims. This cumulative discrimination has a compounding effect, making it even harder for Muslim women to overcome the barriers they face in entering politics. Out of 16 Lok Sabhas since independence, five of them, including the first one, did not have any Muslim women MPs, and the highest number of Muslim women MPs at any given time has never been more than four.

This lack of representation is evident in the current Lok Sabha, where initially only two women MPs were present, with two Muslim women joining through separate by-elections in 2018. An analysis conducted by the Trivedi Centre for Political Data for the 2019 general elections found that out of 1,279 candidates in the first phase only two were Muslim women. In the second phase, out of 1,202 candidates, there were seven Muslim women.

BJP’s empty claims for the Pasmanda

Many BJP leaders, including the current PM Modi have spoken about reaching out to and uplifting backward caste Muslims, that is the Pasmanda, however there is yet to be any action to back the words. They have argued that the Pasmanda have a past Inddic heritage and thus due to being backward they have been sidelined by upper caste Muslims. Hence, BJP has premised to grant them rights. But thus far, it seems, this has been a rhetoric as no concrete steps have been put forth.

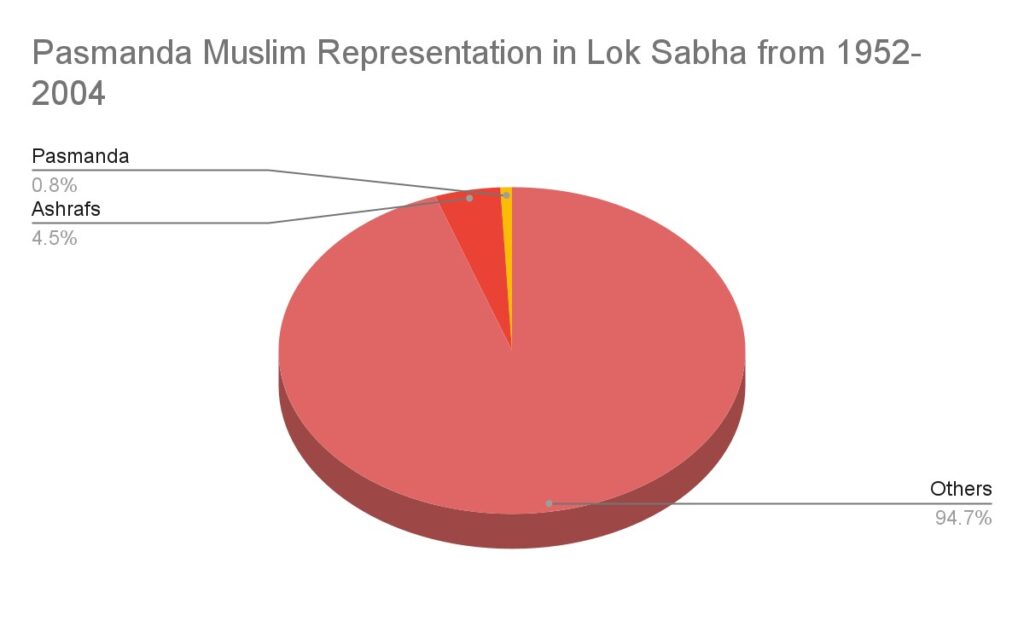

Source: CJP

Khalid Anis Ansari, a well known academic and also a faculty member in sociology at Azim Premchand University, Bangaluru, Ansari points out that out of the 7,500 elected representatives from the first to the fourteenth Lok Sabha, only 400 were Muslims. Among them, 340 were from the Ashraf (upper caste) community, while only 60 were from the Pasmanda background. In the 2011 Census, Muslims accounted for about 14.2% of India’s population. This means that Ashrafs, with a population share of 2.1%, were overrepresented in the Lok Sabha with around 4.5% representation. In contrast, Pasmandas constituted approximately 11.4% of the total population but had a mere 0.8% representation in Parliament.

In fact, while BJP claims to support the cause of the Pasmanda Muslims, it appears as clearly lip service when we see the data.

Alternate Models for Ensuring Representation

The Sachar Committee 2006 recognised and noted the grave lack of Muslims in politics and thus sought to illustrate alternate models successfully adopted by governments to ensure there would one minority voice at the very least. One such case study cited by the Sachar Committee Report observes innovative mechanisms implemented by the Andhra Pradesh government to enhance Muslim and minority participation in decision-making processes, despite their low representation in elected bodies. These mechanisms include provisions for ‘co-opting’ and nominating individuals from minority communities in various institutions.

In Mandal and Zila Parishads, one person from the minority community is co-opted based on prescribed criteria i.e., the individual belongs to a linguistic or religious minority group. A similar provision exists for two persons in Zilla Parishads. These co-opted members can thus contribute to discussions and suggest agenda items, although they do not have the right to vote on collective decisions.

For Municipal Corporations and Municipalities, the Andhra Pradesh Municipal Laws (Amendment) Act enables the co-option of two persons from minority communities. These members can participate in meetings and express their opinions but do not have voting rights. This provision applies to certain Municipal Corporations and Nagar Panchayats.

In Cooperative Banks, a member belonging to a minority community is nominated by the Registrar to participate in committee meetings without voting rights. This provision extends to district cooperative banks and other higher-level cooperative banks as well.

In Agricultural Marketing Committees in fact Andhra Pradesh has implemented an inclusive approach by allowing a total of 14 nominated members from different categories. Five of these nominations are reserved for SCs, STs, BCs, minorities, and women out of the 14 permitted nominations, this ensuring representation of the marginalised as a guarantee.

Overall, these mechanisms provide a minimum level of democratic participation to under-represented segments, including Muslims, although they do not grant significant political power. Co-opted and nominated members are furthermore given the opportunity to contribute to discussions and influence agendas in the respective institutions.

BJP and the Development Myth

The then MPs from BJP, which came into power in 2014, were criticised dearly for their poor performance and lack of accountability. For instance, Sabrang India notes that despite winning the 2014 elections in Uttar Pradesh with promises of development, they failed to utilize a significant government fund of Rs 333.6 crores allocated for improving facilities, education, healthcare, and other essential services in their respective constituencies. This failure was particularly evident in the 33 Lok Sabha seats where both Dalits and Muslims form a significant portion of the population, with Rs 71 crore remaining unspent in Dalit-dominated constituencies and over Rs 64 crore unused in constituencies with a substantial Muslim population.

Despite their underwhelming performance, the BJP has been unapologetic and continues to outspend other political parties in advertising through television, radio, and print media. The Economic Times has reported that the BJP accounted for 59% of the total ad insertions in Goa, Punjab, and Uttar Pradesh between November of the previous year and February 4, 2017. During state elections, the BJP reportedly spent more than Rs 150 crore on advertising, while the combined spending of the Samajwadi Party, Bahujan Samaj Party, and Congress was less than half of the BJP’s advertising share. The SP accounted for 13% of the ad share, the BSP for 12%, and the entire political campaign of the Congress saw ads of around 4%. In January of the same year, a total of 27,133 ads were aired on TV channels, 11,722 ad spots were played on the radio, and 2,797 ads were inserted in print media.

This clearly shows the BJP’s use of muscle power and monopoly over advertisements by spending more and more on trying to increase their electoral gains rather than improve the efficiency of their current working parliamentarians. Muscle power, hate-laced campaigns, which combined with the denial of representation to religious minorities spells a recipe that can effectively erode democracy.

Related:

UP Civic Polls: Clashes Reported in Amroha, Lucknow; Several Muslim Voters’ Names ‘Missing’

Madhya Pradesh Polls: 38 lakh Muslim Voters, Only 4 Candidates

“No harm caused by thirty minutes of Namaz, won’t inconvenience anyone”: Madras HC