Mumbai: Health experts have welcomed the Punjab government’s decision to reverse its recent ban on sale of syringes without prescription. The ban had been an attempt to control rampant drug abuse, but critics had said it would force addicts to reuse and share syringes, causing a spurt in hepatitis B and C and HIV infections, which are commonly transmitted among intravenous drug users.

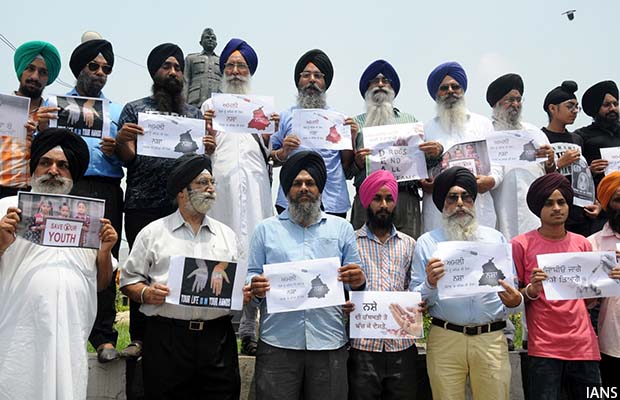

Amritsar: An anti-drug awareness rally

Public health advocates are now calling for the state to ensure all private and public health facilities adopt auto-disable (AD) syringes, which are fitted with safety plungers that break off after a single use–to ensure there is no reuse.

The deputy commissioners of six districts of Punjab had on July 5, 2018, banned over-the-counter sales of syringes at chemist shops and pharmacies, as part of the state government’s renewed crackdown on the use of heroin and other injectable narcotics.

In June 2018 alone, the media had reported 23 deaths from drug overdose in Punjab, placing pressure on the Congress-led state government to curb drug abuse, which had been one of its key election promises.

On winning state assembly elections in March 2017, chief minister-designate Capt Amarinder Singh had claimed he would wipe out Punjab’s drug problem “within four weeks”. He had resolved to set up a task force to work directly under the chief minister’s office. “The STF will launch a crackdown against drug smugglers and small-time suppliers. Psychiatrists would be appointed in drug rehabilitation centres to provide treatment to addicts as they are only consumers,” he was quoted as saying in the Hindustan Times on March 12, 2018.

A massive addiction problem

There are an estimated 860,000 opioid users in Punjab, of which 230,000 are dependent, that is, they need to consume drugs in order to function normally, according to a 2015 study commissioned by the central ministry of social justice and empowerment and the Punjab government.

Heroin is the most commonly used drug in Punjab (53%), followed by opium (33%), with pharmaceutical opioids the least common (14%), the study found.

The addicts were found to be preponderantly male–99%; 76% were aged between 18-35 years; and 89% were literate, with some form of formal education.

The average heroin user spends about Rs 1,400 per day to feed their addiction, more than 3.5 times the state’s daily per capita income of Rs 392 (or Rs 142,958 annually in 2017-18). This figure for opium users is Rs 340 per day and pharmaceutical-opioid users Rs 265 per day, the study said.

The epidemic is estimated to affect up to 67% of families in certain districts of Punjab, and has become a major socio-economic and political issue.

Punjab’s long-running drug abuse problem is attributed to several factors, prime among which is its location along a porous border with Pakistan, which itself is well-connected with the Golden Crescent–an area that covers Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan, one of Asia’s largest opium-producing regions–which enables narcotics to enter Punjab more easily than other parts of India.

There have also been allegations of official complicity in facilitating the trade–especially of the police, which has led to several arrests, as well as of powerful politicians including Bikram Singh Majithia, a minister under the previous Shiromani Akali Dal-led government.

The quick uptake of drugs among young men is blamed on Punjab’s high youth unemployment rate–16.6% of 18-29 year-olds are unemployed, compared to the national average of 10.2%. Lacking the skills to work in the services or manufacturing sectors and facing an increasingly mechanised agricultural industry, many rural, educated youngsters have been left adrift, according to this 2017 research paper.

Recent efforts to fight the problem

Last week, Punjab’s cabinet of ministers decided to recommend to the central government that first-time drug traffickers be punished with the death penalty. The Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (NDPS) Act currently prescribes the death penalty for repeat offenders only.

The move is seen as an effort to quell criticism from opposition parties of the Congress government’s failure to wipe out drugs as promised.

Amid allegations of police involvement in the drug network, on July 5, 2018, Chief Minister Capt Amarinder Singh ordered compulsory annual drug checks for all government employees.

At the same time, some district administrators issued orders prohibiting the sale of syringes without prescription, but the state government distanced itself from the move following criticism that banning the sale of syringes available on the open market could lead to increased sharing and use of discarded syringes, propelling the spread of infectious diseases.

“The intent of solving this problem may be noble, but the management tool being used is questionable,” Rajiv Nath, joint managing director of Hindustan Syringes & Medical Devices Ltd, had told IndiaSpend after the ban was announced. “This will amplify the problem of syringes being reused by drug addicts and accelerate the spread of hepatitis C in Punjab, an area with an already challenged healthcare infrastructure.”

In India, around 40 million people are infected with hepatitis B and at least 6 million with hepatitis C, according to 2017 World Health Organization estimates. While statewide figures for Punjab are hard to come by, a state task force to tackle hepatitis C (HCV) records the prevalence at 3.29%, or about 650,000 patients.

There were 56,975 positive cases of HIV recorded in Punjab in 2017, a positive rate of 1.33%, according to data released by the Punjab State AIDS Control Society (PSACS). Amritsar had the highest number of positive cases at 14,309 (2.58% positivity rate).

Some believed the ban on syringes would disproportionately affect chemists and pharmacy owners, who could face additional harassment from police keen to appear active in the “war on drugs”.

Commentators had also pointed out that getting around the ban would be easy. There would have been nothing stopping drug users from buying syringes online, for example, and often at a cheaper price.

“Remember that since Punjab is so closely located to Chandigarh and Haryana, anyone could just cross over the border and buy syringes there,” Ratti said.

Other solutions

The chief minister’s office, while rolling back the ban, directed deputy commissioners across the state to issue orders to chemists to prepare an inventory of syringes and keep a record of their sales including the buyers’ details.

A solution using a new technology was also suggested–auto-disable (AD) syringes, which are fitted with safety plungers that break off after a single use. All prescriptions must specify the use of AD syringes and both private and public health facilities should accelerate a switch, the Indian Medical Device Foundation suggested in a July 7, 2018, letter to Punjab’s principal secretary of health.

Up to 16 billion injections are carried out across the globe annually, of which 25-30% take place in India and only 37% are deemed safe and necessary.

Concerns around safe administration of injections in India persist, despite economic development and improvements in healthcare. As many as 21 people were reported to be infected with HIV in Uttar Pradesh earlier this year after a health worker used the same syringe on multiple patients, NDTV had reported in February 2018.

AD syringes have been cited as a viable and cost-effective solution to prevent the re-use of syringes and spread of infections, according to a May 2018 Health Technology Assessment study by the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER), Chandigarh.

The Andhra Pradesh government recently issued a notification announcing that all public hospitals in the state would switch to AD syringes by June 28, 2018, which is World Hepatitis Day, based on the recommendations of the PGIMER report.

This is something public health experts would like to see emulated in government policies across the country.

(Sanghera, a graduate of King’s College, London, is an intern with IndiaSpend.)

Courtesy: India Spend