The Election Commission of India (ECI) has rolled out the second and most expansive phase of its Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls across 12 States and Union Territories — Andaman & Nicobar Islands, Chhattisgarh, Goa, Gujarat, Kerala, Lakshadweep, Madhya Pradesh, Puducherry, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal. This phase, announced through an instruction dated October 27, 2025, is pegged to “01.01.2026” as the qualifying date and explicitly cites the June 24, 2025 order for Bihar as its procedural foundation, though with key modifications.

The instruction states that it is an “application of the Bihar SIR guidelines, subject to additions and modifications” — a phrasing that signals both continuity and quiet correction. What emerges is a recalibrated national model that softens the stringent documentation demands that had triggered widespread criticism during the Bihar rollout earlier this year.

The October 27 directive: recalibrating the Bihar model

The October 27, 2025 nationwide instruction now appears as a corrective response to these controversies. It retains the Bihar framework’s administrative skeleton but relaxes the parts that provoked legal and political backlash — particularly the document collection and automatic deletion provisions.

The ECI acknowledges in its circular that the nationwide exercise must account for the “qualifying date of last intensive revision” in each state, many of which go back more than two decades — to 2002 (Gujarat, Kerala) or 2003 (Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh). In such a diverse administrative terrain, a one-size-fits-all demand for citizenship documents was untenable.

Hence, the Commission’s “additions and modifications” represent a recalibrated approach of enumerate first, verify later.

The critical relaxation: no document collection during enumeration

The most consequential change is categorical that “No document is to be collected from electors during the Enumeration Phase.”

This single instruction overturns the Bihar precedent. Booth Level Officers (BLOs) will no longer collect proof of age or citizenship from existing voters at the door. Their task, between November 4 and December 4, 2025, is limited to recording updated data using the new Modified Enumeration Form (Annexure III) and Declaration Form (Annexure IV).

This is not a waiver of verification but a change in timing and logic. Verification is postponed to the claims and objections phase, ensuring that enumeration focuses on inclusion rather than exclusion. It prevents inadvertent disenfranchisement due to logistical hurdles — missing forms, illiteracy, migration, or inaccessible terrain — especially across the island territories (A&NI, Lakshadweep) and rural interiors of Rajasthan, UP, and Madhya Pradesh.

The relaxation also repositions BLOs as facilitators rather than investigators — a shift from the quasi-policing role seen in Bihar’s version.

Enumeration redesigned: linking voters to previous rolls

As per instructions, to ensure continuity and prevent duplication, the ECI has modified the enumeration form to include two new columns that record a voter’s linkage to entries in previous SIR rolls — either of the self, parents, or relatives.

In Bihar, this linkage mechanism had been introduced belatedly, after BLOs reported difficulties in obtaining documents. In the nationwide version, it is embedded from the outset.

Moreover, BLOs can now access the last intensive revision rolls of any state, not just the one in which the voter currently resides. For example, an elector earlier registered in West Bengal’s 2002 roll can use that entry to retain enrolment in Tamil Nadu — a move that particularly benefits internal migrants and mobile working populations.

From proof to continuity: a different evidentiary standard

The nationwide SIR also redefines what counts as proof of eligibility. Under the Bihar model, most voters registered after 2003 had to produce one of the eleven listed documents — ranging from ration cards to land records — to retain their place on the rolls.

Under the new approach, documents are only required for those not appearing in any state’s previous SIR roll. For all others, linkage itself establishes continuity. This modified framework prioritises historical presence over paperwork, effectively shifting the evidentiary standard from documentary proof to administrative traceability.

For first-time voters turning 18, the process is also streamlined. Instead of waiting until the claims-and-objections period, Form 6 applications can be filed alongside the SIR declaration during enumeration itself.

Non-inclusion protocol: ECI replaces automatic deletion

Another significant change concerns the treatment of unreturned enumeration forms.

In Bihar, failure to submit the form by the July 25, 2025 deadline risked automatic exclusion from the draft rolls. The new nationwide instruction explicitly prohibits such deletion without investigation.

If an elector’s form is not returned, the BLO must determine the probable cause — whether the person is absent, has shifted residence, is deceased, or appears as a duplicate — based on local inquiry.

Instead of silent removal, the directive mandates public disclosure:

“Booth-wise lists of electors whose names are not included in the Draft Roll shall be displayed on the Notice Board of respective Panchayat Bhavan/Urban local body office and on the CEO’s website.”

This requirement for both physical and digital publication marks a structural transparency mechanism absent in Bihar. Non-inclusion is now a verifiable administrative act, open to scrutiny and contestation during the claims and objections phase.

Such public display may appear procedural, but in practice, it serves as a safeguard against arbitrary disenfranchisement — a concern repeatedly voiced during the Bihar hearings.

Staggered scrutiny: verification after draft publication

The ECI’s new timeline formalises a two-step structure:

- Enumeration and Draft Roll Publication (Nov 4 – Dec 9, 2025)

- Claims, Objections, and Verification (Dec 9, 2025 – Jan 31, 2026)

Under this model, notices to electors whose enrolment cannot be linked with any previous SIR roll will be issued only after the draft publication. This ensures that the BLO’s November work focuses solely on accurate data collection, not document policing.

By de-linking enumeration from verification, the Commission implicitly acknowledges the impracticality of its earlier Bihar model, which conflated both into a single, high-pressure phase.

| Key differences between Bihar SIR and Nationwide SIR | ||

| Sr. No. | Bihar SIR | Nationwide SIR |

| Enumeration phase | ||

| 1. | Enumeration centred on verification; existing electors registered after 2003 were required to furnish documents proving age and citizenship to retain their names on the rolls. | Enumeration focuses on inclusion; enumerators trace electors using entries in previous SIR rolls of self, parents, or relatives. No documents are required at this stage.

|

| Enumeration form design | ||

| 2. | The linkage to earlier rolls was introduced later during field implementation, after officers reported difficulties in obtaining documents. | The enumeration form now includes two new columns to record the link between electors and their entries (or relatives’) in the last intensively revised rolls from the outset.

|

| Scope of Roll linkage | ||

| 3. | Linkage was restricted to Bihar’s 2003 revision rolls; Booth Level Officers (BLOs) could only search within the state. | Linkage can now be made to any state’s last intensive revision roll; BLOs have access to previous revision rolls of all states. |

| Voters’ Proof and Documentation Requirement | ||

| 4. | Most voters registered after 2003 had to produce one of the 11 prescribed documents to confirm eligibility. | Documents are required only for electors not appearing in any state’s previous SIR roll. Others can establish continuity through linkage without submitting documents. |

| Claims-and-Objections Period | ||

| 5. | Notices to prove eligibility were issued only to electors whose inclusion was challenged or who failed to produce documents. | Notices will be sent to all voters not found in any previous SIR roll; their inclusion will depend on document verification during hearings |

| Cross-State Continuity for Migrant Voters | ||

| 6. | Electors could only rely on Bihar’s 2003 roll.

| Electors can rely on any previous roll from any state (for example, a name in West Bengal’s 2002 roll can help retain enrolment in another state like Tamil Nadu). |

| Citizenship Verification Approach | ||

| 7. | Citizenship verification was treated as a central test; electors had to provide documents proving citizenship and age. | Citizenship continues as an eligibility criterion but is not invoked as the central test; Aadhaar remains one of the listed documents. |

| Inclusion of New Electors | ||

| 8. | Form 6 applications from new voters (those turning 18) were accepted after the enumeration phase, during the claims-and-objections period. | New electors can file Form 6 together with the SIR declaration during enumeration itself. |

| Consultation and Preparatory Steps | ||

| 9. | Implemented with limited advance notice and minimal consultation with political parties. | Begins with meetings between Chief Electoral Officers and political parties in each state to explain the process and ensure participation from the start. |

ECI’s October 27, 2025 instructions [Nationwide SIR covering 12 States and UTs] can be read here

A nationwide rollout shadowed by Bihar’s controversy

The ECI’s nationwide SIR plan, formally discussed at the Third Conference of Chief Electoral Officers (CEOs) held in New Delhi on September 10, 2025, was conceived as a “unified” exercise to clean and update voter rolls. Yet, state-level realities have exposed deep procedural differences.

In Bihar, the SIR had snowballed into a controversy over legality and intent, as the state’s entire voter list was placed under re-enumeration. Booth Level Officers (BLOs) were directed to visit every household, distribute pre-filled forms, and collect documentary proof of citizenship and age from all existing electors, even those long registered. This effectively turned the revision into a de facto verification drive, with the burden of proof shifted onto the voter.

The June 24, 2025 notification — later at the heart of several petitions — stated that if any Electoral Registration Officer (ERO) or Assistant ERO “doubts the eligibility of a proposed elector due to non-submission of documents or otherwise,” they must initiate suo motu inquiries, issue notices, and even refer “suspected foreign nationals” to the competent authority under the Citizenship Act, 1955. This language blurred the line between electoral roll management and citizenship verification — a domain constitutionally outside the ECI’s scope.

Then June 24, 2025 Bihar SIR instruction can be read here

Organisations like the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), and several political parties, challenged both the suddenness and scope of the Bihar exercise. The controversy deepened when complaints emerged of BLOs supplying single copies of forms — even though electors were asked to submit duplicates — and of undue pressure and unrealistic deadlines.

Judicial intervention: Supreme Court steps in

By early September, the Supreme Court of India had stepped in. During hearings on petitions challenging the Bihar SIR, the bench led by Justices Surya Kant and Joymalya Bagchi scrutinised the ECI’s insistence on document submission and its implied role in assessing citizenship. The Court’s September 8, 2025 order became a turning point, reported LiveLaw.

The judges clarified that Aadhaar could be accepted as a form of identity proof, but “not as proof of citizenship.” The order, while limiting the ECI’s overreach, also introduced Aadhaar as the 12th acceptable identity document, in addition to the eleven previously listed in Annexures C and D of the June 24 order. The Court explicitly directed that any refusal to accept Aadhaar “shall be treated with utmost seriousness.”

In compliance with the Supreme Court’s direction, the Election Commission of India issued instructions to the Chief Electoral Officer, Bihar, on September 9, 2025, regarding the use of Aadhaar during the Special Summary Revision (SIR).

ECI’s instruction on Aadhaar dated 09.09.2025 can be read here

This judicial correction reshaped the SIR framework — it drew a clear legal boundary: identity verification is permissible under the Representation of the People Act, 1950 (Section 23(4)), but citizenship assessment is not. In effect, Bihar became a national test case, forcing the Commission to recalibrate its process before extending it to other states.

West Bengal: historical mapping, administrative delinking

In contrast, the Telegraph reported that the West Bengal’s SIR has been structured around a different logic — a historical mapping rather than re-enumeration. Here, the ECI has ordered a house-to-house verification based on the 2002 voter list, the last time an intensive revision was conducted in the state. BLOs have been tasked to cross-check every current elector against the 2002 roll, verifying continuity rather than demanding documents anew.

Those whose names appear in both lists will not need to provide any proof. Their children — if enrolled after 2002 — can use their parents’ details to establish linkage. For those not found in the 2002 list, BLOs will collect information for possible inclusion during the upcoming claims and objections phase.

This approach — seemingly technical — carries significant administrative and political undertones. Alongside the mapping, the ECI has delinked the Chief Electoral Officer’s (CEO) office from West Bengal’s Home and Hill Affairs Department, relocating it to premises under central government control. The official reasoning: “administrative neutrality.” But in a state long governed by an opposition party, the move raises questions of trust and control.

While the Commission cites the Representation of the People Act, 1950 to justify the delinking, observers point out that similar interventions are rare in BJP-ruled states, suggesting an uneven application of the principle of neutrality.

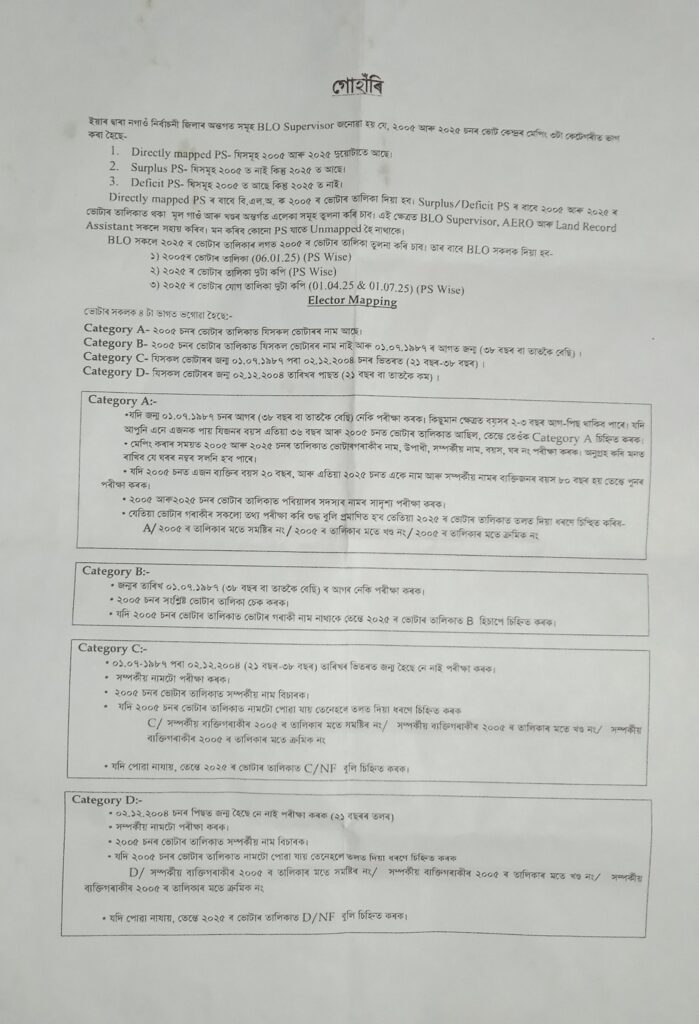

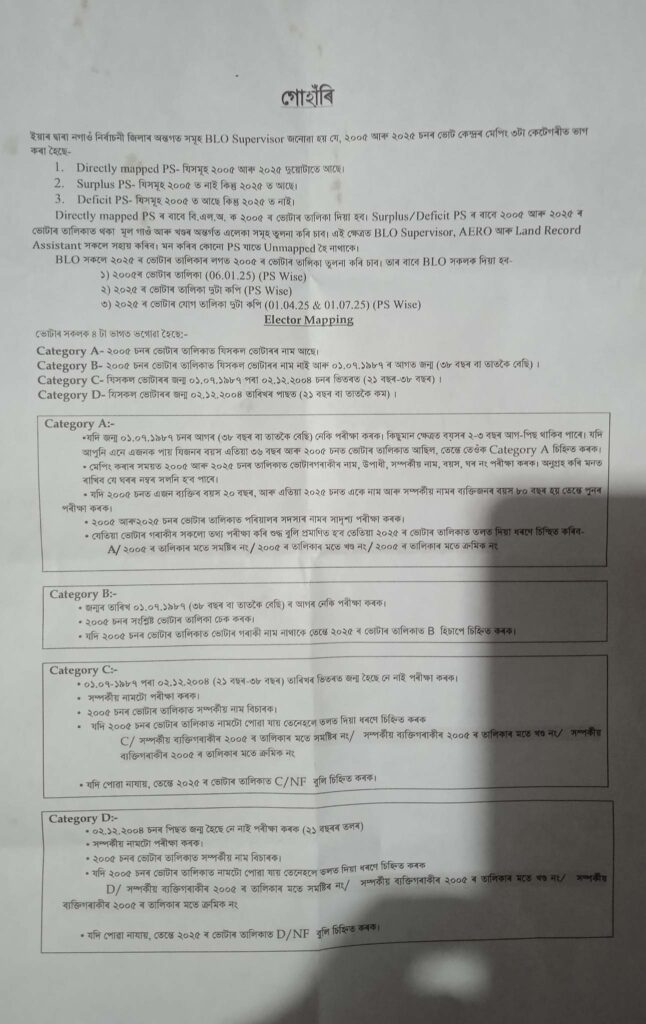

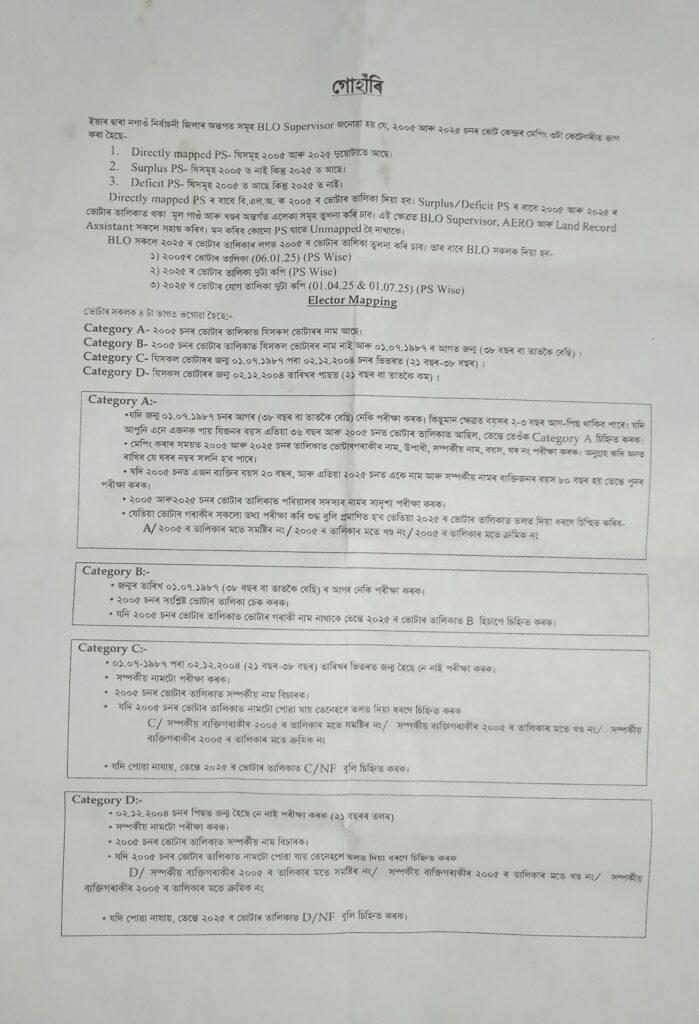

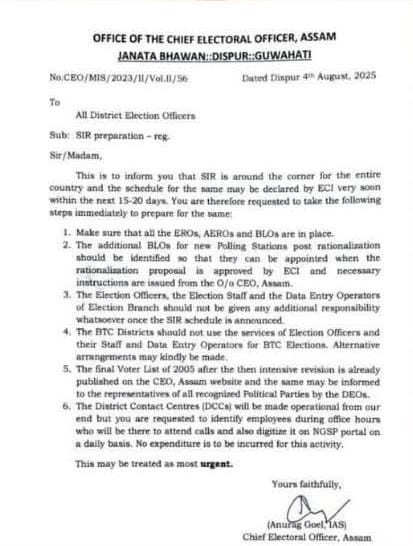

Assam: citizenship and the politics of exclusion

Nowhere, however, does the SIR intertwine as closely with citizenship politics as in Assam. The state’s revision, announced in August 2025, echoes long-standing anxieties around “illegal voters” — a phrase deeply enmeshed with the National Register of Citizens (NRC) debates. The ECI notification is available on social media:

The Times of India reported that, Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma publicly declared that the SIR would “cleanse” the rolls. Assam’s Chief Electoral Officer (CEO) Anurag Goel instructed district officials to complete preparations within twenty days — a pace that mirrors the high-pressure Bihar exercise. The reference point here is the 2005 revision, now being shared with political parties for comparison.

In practice, this has revived fears of selective scrutiny. By tying roll verification implicitly to citizenship, the Assam model reinforces the same grey area that the Supreme Court cautioned against in the Bihar case.

This triangulation — Bihar’s judicially restrained overhaul, Bengal’s archival verification, and Assam’s politically charged exercise — lays bare the “unified yet differential” nature of the ECI’s national plan. The SIR may be centrally conceived, but its execution remains fragmented by context, court, and politics.

The larger question: a unified process, differential application

The ECI’s nationwide SIR now rests on a paradox. It is designed as a unified exercise — same schedule, same forms, same qualifying date — but its ground implementation is explicitly differentiated by context and constraint.

- Bihar’s SIR remains judicially supervised, its documentation policy rewritten by the Court.

- West Bengal’s process is historically anchored and administratively separated from the state government.

- Assam’s revision remains entangled in citizenship discourse.

- And in the rest of the twelve states, the process is now being executed under a relaxed documentation regime that acknowledges the backlash from Bihar.

The result is a single national framework fragmented into state-specific realities — a nationwide SIR that, in effect, mirrors the country’s political and administrative diversity rather than uniformity in it.

Recalibration, not reconciliation

The October 27, 2025 instruction marks a strategic recalibration — a conscious step back from the hyper-bureaucratic and citizenship-linked model that defined the Bihar SIR. The nationwide SIR instructions seem to prioritise inclusion, transparency, and procedural fairness over immediate verification, while retaining the ECI’s control over the pace and design of the process.

Yet, this recalibration does not necessarily resolve the underlying questions:

- Can a constitutionally independent body modify its own guidelines mid-course without admitting procedural error?

- Does judicial oversight in one state suffice to ensure uniform legality nationwide?

- And, most crucially, does decentralised implementation enhance democratic participation — or risk producing uneven standards of electoral inclusion?

As the nationwide enumeration begins on November 4, 2025, the ECI finds itself balancing between correction and continuity. The revised framework avoids the pitfalls of Bihar’s coercive verification, but its differential application across states suggests that India’s “unified” SIR remains, in practice, a patchwork — legally restrained, politically contested, and administratively uneven.

Related:

ECI’s nationwide SIR plan: a ‘unified’ push, applied differentially across states

89 lakh complaints of irregularities during Bihar SIR were rejected by ECI: Congress