The 2017-18 budget is an opportunity for the government to concentrate on improving school education for over 260.5 million children who enrolled in elementary and secondary school in 2015-16–children who will form the core of India’s working-age population, one billion by 2030, the largest in the world.

“Business as usual” will not solve the problem, submitted Pratham, an education nonprofit, in a pre-budget consultation with India’s finance ministry. “Unless major shifts are undertaken on an urgent basis to build children’s foundational skills, we are losing huge opportunities each year for improving the life chances of an entire generation of children and youth in this country,” the consultation note added.

IndiaSpend reached out to the education ministry for a comment on the 2017-18 budget, but we had not received a response at the time of publishing. (This story will be updated if and when the ministry responds.)

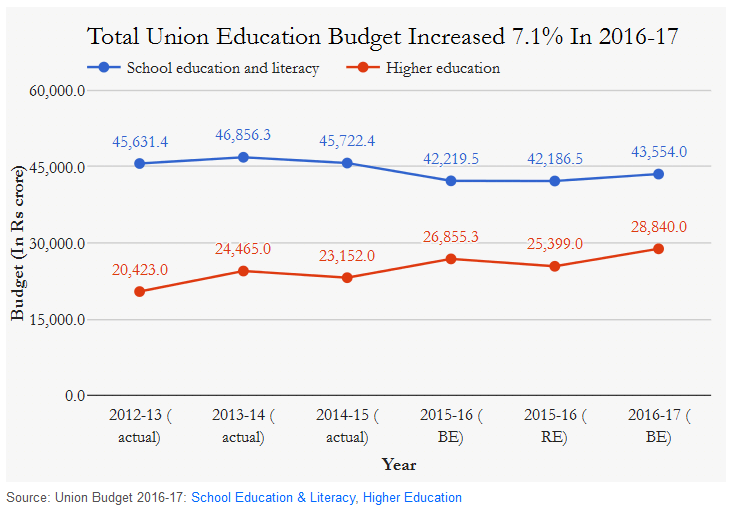

Higher education dominated last year’s education budget (with an increase of 13% over the 2015-16 budget) and the conversation about education–with policies for improving the quality and ranking of higher education, creation of a higher-education financing agency, and approval of new higher-education institutes–even though only 34.2 million enrolled in higher education institutions in 2014-15 or, a seventh or fewer than those enrolled in school.

In contrast, the school education and literacy budget increased 3.2% in 2016-17, compared to 2015-16 revised budget estimates, according to union budget data.

Over the financial year 2016-17, the central government allocated Rs 43,554 crore to school education and literacy, and Rs 28,840 crore to higher education.

Low school outcomes result in a less-productive workforce

In 2014, though the government implemented a programme, ‘Padhe Bharat Badhe Bharat (If India learns, India advances)’, to improve early grade reading, writing and math, data on learning outcomes do not show improvements in rural schools. For instance, elementary school education in public and private schools is plagued with low outcomes–46.1% of grade I rural children couldn’t read letters in 2016, while 39.9% couldn’t recognise numbers 1 to 9, according to the Annual Status of Education Report.

If children do not have basic education–reading, writing, comprehension and math skills–India will have a workforce that is unproductive, not fit to be hired, and unprepared for higher education or skill development.

“It is clear that for quality and outcomes to improve in higher education, much more focus and investment is needed in elementary education,” wrote Rukmini Banerji, chief executive officer of Pratham, in an email to IndiaSpend.

The low level of education is also reflected in a drop in secondary school enrolments. In 2015-16, 88.94% of primary school-age students enrolled in primary school, compared to 51.26% of secondary-age students in secondary school, according to data from the Unified District Information System for Education.

2017-18 budget should focus on improving school outcomes

Along with increasing the amount spent on education, the budget also needs to be restructured to focus on learning outcomes, and monitoring of quality.

“There is a significantly low proportion spent on learning enhancement,” while more attention is paid to inputs such as schools and books, said Avani Kapur, senior researcher at Accountability Initiative, a New-Delhi based nonprofit. She explained that the NITI Aayog, the government think-tank, plans to start ranking states, using the school education quality index, one indicator of which would be school learning outcomes. “Orienting the budget more towards learning outcomes could move this agenda forward,” she added.

Further, delays in decision-making and fund-flows have led to major delays in programme implementation, according to Pratham’s note to the finance ministry. Even though the school year begins in April in most schools, learning enhancement programmes often get implemented between September and November, wasting much of the school year.

The government does not monitor learning outcomes regularly. For instance, the annual report on schools includes information on enrolment, and number of teachers, but not on the quality of education.

The government started a school standards and evaluation programme, called ‘Shala Siddhi’, in 2013, which is primarily based on self-assessment by schools and school examinations. Until now, no report has been published as the government is collecting information from the states, according to a person who works with the programme.

One government measure of learning, the National Achievement Survey will now be conducted every year, instead of every three years, according to press release from the Ministry of Human Resource Development.

But the education ministry should ensure states know how to conduct measurements well, and that available data are used to improve learning, according to Pratham’s pre-budget submission to the finance ministry.

The ministry of human resource development prepared an outcome budget for 2016-17, outlining activities and effects on enrolment, gender equality and more. But there was no clear outcome on learning levels. The budget outlined one outcome as “enhanced learning levels and retention” with no specific measures for the outcome.

One way of improving learning outcomes through the budget could be through outcome-linked financing, suggested Kapur, the researcher at Accountability Initiative. For instance, the central government could provide 10% of aid to the states only if they reach certain pre-decided outcomes, such as learning goals.

India’s education spending lower than other BRICS countries

Total central government education spending in 2016-17 on school education made up 2.68% of India’s gross domestic product, according to calculations by the New Delhi-based Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability (CBGA), a budget research and advocacy organisation.

In 2015-16, Indian central government spending on school and higher education was less than other BRICS countries–India spent 3% of its gross domestic product (GDP) on education, compared to 3.8% in Russia, 4.2% in China, 5.2% in Brazil, and 6.9% in South Africa, according to 2016 data from India’s Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation.

“There is an urgent need to increase financial resources” for school education, said Protiva Kundu, lead researcher at CBGA. Based on an analysis of 10 state education budgets, she said education is not a priority for all states.

This 2017-18 central education budget might be 10%-12% more than last year’s budget, according to a January 2017 report in Livemint.

This is the first of Indiaspend’s budget primers. We will also be fact-checking the statements made during the budget on February 1, 2017, on our Twitter timeline here.

(Shah is a writer/editor with IndiaSpend.)

Courtesy: India Spend