As Varanasi goes to polls the jheeni jheeni chadariya of its composite culture is under threat

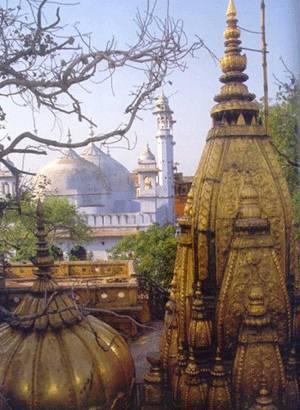

Kashi Vishwanath Temple and Gyanvapi Mosque

The elections in Varanasi are taking place at a delicate juncture. It is not just Modi and BJP versus Gathbandhan. Varanasi has symbolised a richly vibrant syncretic culture that emerged over the centuries. Kabir and Raidas (or Ravidas) contributed to it as did various Urdu shayars of yore. Premchand and Dhumil arose from here, as did Bismillah Khan. Mandirs and masjids coexisted as did weavers’ guilds and unions of mallahs. All this is sought to be crushed under a ritualistic and regressive juggernaut, ignorant of history and culture.

Uttar Pradesh, over the last five years, has been a hotbed of communal politics. Since the Muzaffarnagar riots in 2013, the state has witnessed a vicious brand of communal politics actively organised by the Sangh and the BJP. The rise of the Yogi regime further aggravated this trend. In Varanasi too there have been concerted efforts at communal polarisation.

It is understandable why Varanasi would be a soft target for the Hindutva brigade. Varanasi has a history of temple-mosque politics which is similar to that of Ayodhya before the Babri Masjid was demolished. The Sangh believes that the Gyanvapi masjid in Varanasi stands on the same ground that the original Kashi Vishwanath temple stood upon. One of the slogans raised during the Babri masjid demolition was “Yeh toh sirf jhanki hai, Kashi-Mathura baki hai.” Over the years, this issue has been consistently used by the Sangh to whip up communal sentiments. In fact, locals allege that the current demolition drive in the area to create the Kashi Vishwanath corridor brings the Hindutva brigade one step closer to demolishing the mosque.

Another reason why Varanasi has been such an important target for the BJP is that it has historically been a symbol of cultural and social syncretism. The famed Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb of the region, which involves mixing and acceptance of different cultures and religions, has for long found strong expression in Varanasi. Traditionally, the cultural ethos of the city has gone beyond the narrow “peacekeeping” notion of secularism to that of whole-hearted mutual embrace.

One of the greatest musicians to ever come from Varanasi was Bismillah Khan, the shehnai maestro, who single-handedly brought the instrument that was earlier only played in temples and weddings into mainstream Hindustani classical music. Bismillah Khan embodied the syncretism of Varanasi, embracing many religions and traditions at once. He would often say that music was his true religion. He had an undying love for the city. At a time when most other music practitioners of some fame, like Ravi Shankar, decided to move on to greener pastures and never look back, Bismillah Khan never left Varanasi.

The relationship between Varanasi and literature is also rich and diverse. As against popular perception, the city finds mention not only in Hindu scriptures, but also in the imagination of Urdu poets such as Ghalib. Ghalib composed a poem of 108 couplets, Chirag-e-dair (The Lamp of the Temple), based on Vanarasi, which he visited in 1827. About Varanasi he had to say: “Zamane bhar Mein / yeh sthal / Mukaam-e-fakher / kehlata hain// Dehli shaher bhi / iski / parikarma ko / Aata Hain.”

Varanasi itself has seen many Urdu poets, like Nazeer Banarasi and Rashid Banarasi, both of who belonged to the weavers’ community. Nazeer Banarasi wrote extensively about India, its festivals and politics. Rashid Banarasi, in one of his poems, says that the Ganga protects those who respond to the conch of Hindus, the call to prayer of Muslims, the devotional songs of Sikhs, and the church bells of Christians. Not only Urdu poets, the city has produced legendary Hindi poets as well. Dhoomil (Sudama Pandey), was widely known for his revolutionary poetry, who was also from Varanasi. A host of other progressive writers, such as Premchand, Kashinath Singh, and Namvar Singh, who were ahead of their times in the themes they wrote about, also hailed from Varanasi.

Varanasi’s tryst with poetry of tolerance and syncretism of course goes much further back. Two saint poets, who stood for their own unique and emancipatory philosophy, both from Varanasi, were Kabir and Raidas (or Ravidas). Kabir denounced both Islam and Hinduism, even while embracing them both. He belonged to the working class, whereas Raidas was a dalit who was not even allowed to enter the city. Both are still as relevant and revolutionary today as they were in their lifetimes.

It is worth mentioning here that a large part of the economy of Varanasi consists of the production and trade of sarees. The weavers who make these sarees and silk materials are Muslims, and they are traded by Hindus. The famed Banarasi Saree is largely crafted by Muslim weavers in the area.

Though Varanasi has been simmering since the demolition of the Babri Masjid and has mostly seen the BJP in power in recent times, the city was also once a bastion of the Left. This was due to a large number of trade unions, not just in the saree and silk trade, but also among the artisans who produce wooden toys and brass goods which the areas is known for. There have also been prominent leaders of the left, such as Rustam Satin, who have made lasting contributions to the cultural vibrancy of Varanasi.

As we enter the last phase of polling, it is important to remember all that is at stake here. Hanging in the balance is our prized composite inheritance. What can be said about Varanasi can also be said about the country as a whole. The very secular fabric of our nation is being destroyed by the Hindutva brigade, and it must be stopped.

Courtesy: Indian Cultural Forum