A recently released report on the Nutritional Status of Urban Population by National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau (NNMB), throws light on the chronic undernutrition faced by India’s urban population, particularly the urban poor.

The report compares the average consumption of different food groups by the urban population, to the scientifically calculated Required Dietary Allowance (RDA). RDA, for any food group, is the amount which a person needs to consume every day to avoid malnutrition. Upon such comparison, it was found that India’s urban population, which constitutes about more than 30% of the country’s population, consumes far lower amounts than what is required to stay healthy, of most food groups.

An average urban household consumes only 69% of the RDA for cereals and millets. This means that they fall short of the RDA by 31%. Similarly, most households consume only 81.3% of the RDA for milk and milk products and only 59.5% of RDA for green leafy vegetables.

In contrast to these shortfalls, the consumption of Roots and tubers was 188% of RDA and the consumption of oils was 159.5% of the RDA. Clearly, it shows that the families’ consumer more of the cheaper food groups.

This pattern of food consumption had a direct impact on the health and well-being of the families, with the population being deficient in most of the vital nutrients.

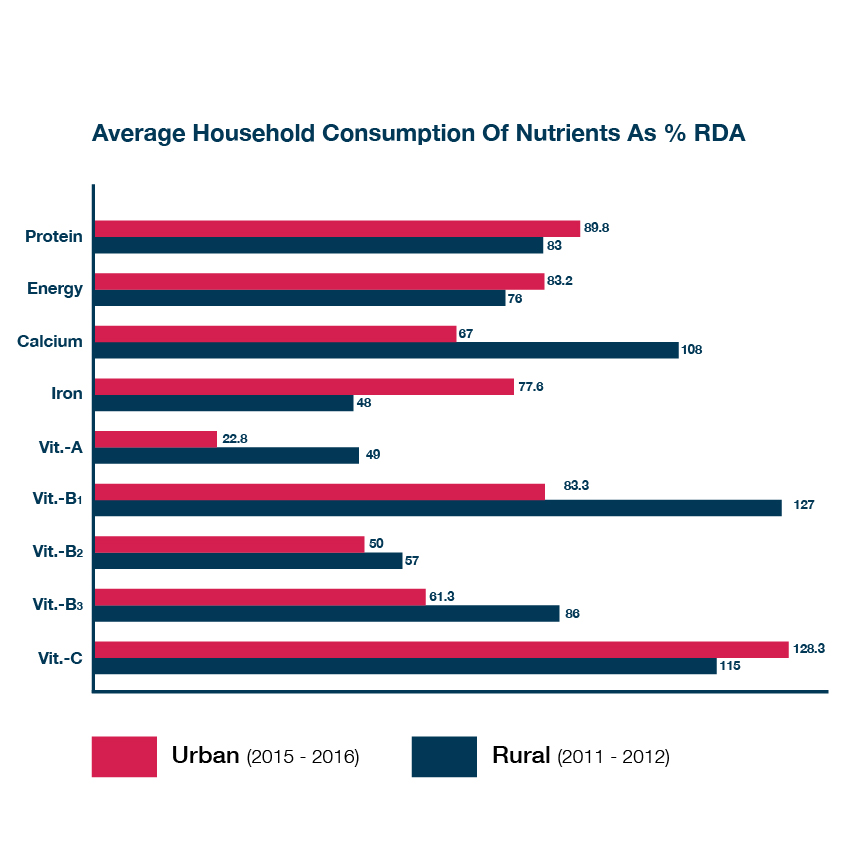

The average urban family was deficient in the macronutrients – protein and energy, both falling short of the RDA. The average family was also deficient in vital micronutrients. The intake of Calcium, Iron, Vitamin B1 and Vitamin B3 was significantly lower than the RDA, while the intake of Vitamin B2 and Vitamin A were abysmal at 50% and 23% of the RDA.

Families have sufficient intake of only two important nutrients, Vitamin C and Vitamin B9.

The effect of the insufficient nutrient intake has a particularly large impact on the children from urban families, with more than 25% of children below 5 years of age suffering from undernutrition. The report also indicates that children from urban poor and deprived communities are the most affected by undernutrition.

It is generally thought that malnutrition is a problem of rural India. But when we compare the present report with a similar one on rural India, brought by NNMB in 2012, the extent of undernutrition is not significantly different in urban and rural areas. For example, an average rural family, in 2012, was consuming 85% of the RDA for protein as opposed to 89% by an average urban family in 2016.

What is the reason behind the persistently high rates of undernutrition, even though India has grown at very high rates in the past decade and more?

The government claims that poverty rate in India has fallen from 45% to 21.9%, between the 1990s and the 2010s. If that is indeed the case, it is a significant reduction in poverty, by more than half. But the data on undernutrition gives a different and a less optimistic picture. Between the 1990s and 2010s, the percentage of children (under 5) who were underweight fell from 43% to 35%. A modest fall of 7 percent compared to a fall of 25 percent in the official poverty rate.

Could it be that the so-called trickle down of economic growth to the poor urban working class was not substantial enough to compensate for the gradual withdrawal of the government from the provision of affordable food in the form of Public Distribution System (PDS) and other welfare schemes?

It has been widely covered by many researchers, how a shift to a targeted form of PDS, where families were arbitrarily classified as below poverty line (BPL) and Above Poverty Line (APL) deprived many families of affordable rations, thereby negatively affecting the nutritional status of these families. The results are clear to see in the data above. Undernutrition persists despite the decline in official poverty figures.

The poor coverage of ICDS (Integrated Child Development Services) in the urban areas, could also be a significant reason behind the dismal nutritional indicators of children in urban areas. Even though urban population constitutes 31% of India’s total population, only 10% of the ICDS projects are allotted to urban areas and only 8% of all Anganwadi centres are situated in urban areas.

A significant part of urban working families, who live in unregistered slums, by the same reason are denied access to ICDS. Similarly, the poorest of the urban families which tend to migrate to different regions, depending on the availability of work, loose access to ICDS. As a result, children and pregnant women who are most vulnerable to undernutrition in urban areas, are not served by ICDS. These same factors also affect the access of the urban poor to PDS, which has already been diluted through targeting.

One hopes that the NNMB report will open the eyes of the establishment towards the need for a universal public distribution system. Considering the under consumption of a wide variety of essential nutrients government must include a larger range of food groups to be covered under the PDS. It is also the need of the hour to expand ICDS infrastructure in the urban areas, to serve the needs of the most vulnerable of the urban poor.

Courtesy: Newsclick.in