The Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) is once again under scrutiny — not for defending artistic expression, but for systematically undermining it. Recent controversies surrounding Phule and Punjab ’95 expose a disturbing trend: when filmmakers dare to interrogate India’s entrenched hierarchies — be it caste oppression, Brahminical dominance, or unchecked state violence — their work is subjected to excessive scrutiny, prolonged delays, and a litany of cuts or title changes. The CBFC, far from being a neutral certifying body, appears increasingly complicit in advancing a political project — one that rewards films reinforcing majoritarian or state-sanctioned narratives with easy certification and even public endorsement, while obstructing those that challenge dominant power structures.

This selective censorship doesn’t just stifle dissenting voices — it shapes the nation’s cultural memory. By muting anti-caste icons, distorting histories of resistance, and erasing portrayals of state brutality, the CBFC is actively curating what stories are allowed to be told, and by extension, what truths can be collectively remembered. What remains is a sanitised cinematic landscape, stripped of its radical edges and emptied of the marginalised voices that once sought to fill its frames.

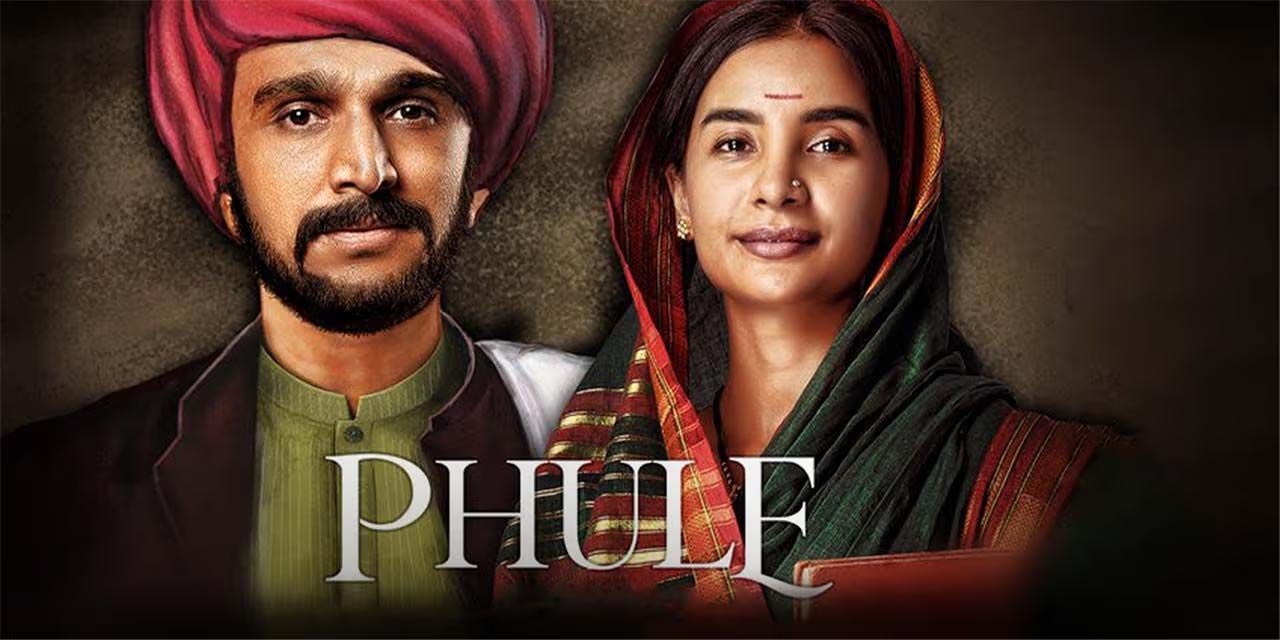

Phule: When telling the truth becomes ‘too casteist’

Ananth Mahadevan’s Phule, a biopic starring Pratik Gandhi and Patralekhaa, tells the story of Jyotiba and Savitribai Phule — pioneering 19th-century anti-caste reformers who fought Brahminical patriarchy, opened schools for women and Dalits, and laid the foundation for radical social change. The film was timed to release on April 11, 2025, Jyotiba Phule’s birth anniversary, but was postponed to April 25— after the CBFC demanded the removal or alteration of multiple words and lines related to caste and historical oppression.

Among the cuts were references to specific caste groups (“Mahar”, “Mang”), systems (“Manusmriti”), and regimes (“Peshwai”), as well as lines like “3,000 saal purani gulaami” (3,000-year-old slavery), which the CBFC asked to be softened to “kai saal purani hai” (it is ancient). References to Manu, caste, and the ideological roots of the Varna system were deemed “sensitive,” effectively scrubbing the Phules’ own language and political vocabulary from their story.

These interventions came after lobbying from Brahmin organisations such as the Brahmin Federation, led by Anand Dave, who claimed the film unfairly demonised Brahmins and failed to acknowledge those among them who had supported Phule. This is despite the fact that Phule’s writings — including Gulamgiri — explicitly and systematically critiqued Brahminism and caste violence. By censoring casteist realities, the CBFC has not just interfered with a film; it has interfered with a historical reckoning.

As director Mahadevan put it while speaking to Times of India, “We should not sugarcoat history.” He revealed that the film’s script was based on extensive archival research, including Phule’s own writings, government records, and educational archives. He had deliberately chosen not to romanticise or soften the injustices of the time. That the CBFC found the truth too inflammatory speaks volumes.

Political leaders like Jitendra Awhad (NCP-SP) publicly condemned the CBFC’s decision, accusing the board of succumbing to pressure from upper-caste groups. “What is true must be shown,” Awhad stated, warning against the sanitisation of social justice struggles in popular media. The episode reignites long-standing questions: whose history is acceptable to depict on screen? And who gets to decide?

Silencing the struggles of the marginalised

Phule is not the only film to face such erasure. In fact, its very existence is an exception — Hindi cinema has rarely engaged with Dalit-Bahujan histories in a meaningful or centralised way. Earlier Marathi films like Mahatma Phule (1954) and Satyashodhak (2023) have attempted to honour his legacy, but no Hindi-language film with a nationwide release has previously placed Jyotiba or Savitribai at the centre of the frame.

The CBFC’s actions have the potential to ensure that such legacies remain ghettoised within regional spheres. Its interventions render Phule’s politics legible only in diluted, caste-neutral terms — which is antithetical to the very purpose of their lives’ work. This signals a broader refusal to engage with the intellectual and political lineage of caste annihilation movements. In censoring Phule, India is not just denying a film; it is denying memory.

Punjab ’95: Sanitising the state’s sins

In a similar vein, Punjab ’95 — directed by Honey Trehan and starring Diljit Dosanjh — faced an even more severe gauntlet from the CBFC. The film is a biopic of Jaswant Singh Khalra, the human rights activist who exposed the illegal mass cremation of over 25,000 Sikhs killed in fake encounters during the Punjab insurgency. The CBFC initially demanded 85 cuts, later escalating to nearly 120, including removing references to specific locations, Sikh scriptures, international bodies, and — most damningly — Khalra’s name and the film’s title.

Khalra’s widow, Paramjit Kaur Khalra, had condemned the demands, reminding the public that the film had been made with the family’s full consent. As per Hindustan Times, she had noted, “Hiding Punjab’s truth will benefit no one.” The Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) also defended the film’s accuracy and called for its unaltered release. The struggle that movies who depict a historical event of India’s past, which might want to be forgotten or ignored, is emblematic of how truth itself is policed.

The politics of what gets censored — and what doesn’t

These censorship decisions are not isolated or apolitical. Films like MSG-2: The Messenger (2015), which portrayed Adivasis as “shaitans” (devils), were allowed to release — and even received enthusiastic endorsement from followers of Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh, despite his criminal convictions. The Kashmir Files (2022) and Kerala Stories (2023), accused of communal polarisation, received tax exemptions and direct political promotion. In stark contrast, films like Haider (2014) and Udta Punjab (2016) faced extensive censorship for exposing state violence or drug abuse.

This contrast underscores a chilling trend: the CBFC functions less as a neutral regulator of public sensibilities, and more as an ideological gatekeeper. Stories that challenge Hindu upper-caste hegemony or question state violence are obstructed; stories that reinforce them are amplified.

Conclusion: Censorship as historical violence

The CBFC’s treatment of Phule and Punjab ’95 reveals a deeper crisis of memory in India. Censorship is not merely about content — it is about control over collective narratives, about what histories are allowed to survive. In rendering caste violence “too sensitive” for public viewing, the state sends a clear message: caste can be discussed, but only within state-sanctioned parameters. Similarly, police brutality and human rights violations can be mentioned — but only if the perpetrator is not the state itself.

At stake is not just artistic freedom but historical truth, democratic debate, and the public’s right to remember. To censor films like Phule and Punjab ’95 is to erase the very people and movements who fought to make India more equal, more just, and more humane. If the truth makes some uncomfortable, that is all the more reason for it to be shown.

Related:

Fiction as history and history honestly portrayed: a tale of two films and a documentary

Congress Radio, the power of revolutionary change: Lessons from ‘Ae Watan Mere Watan’, the film