Bengaluru: “Climate change in India will soon become critical.”

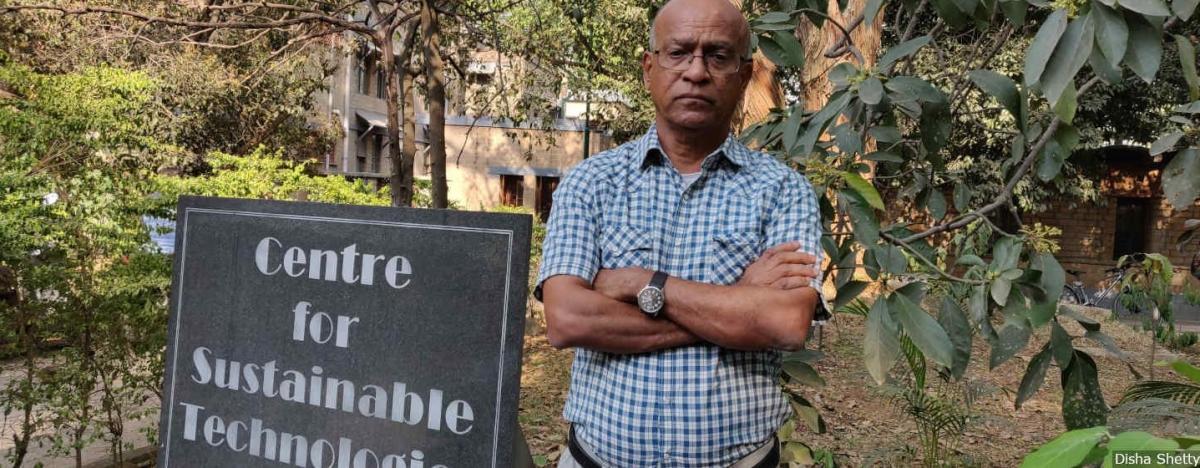

N H Ravindranath, a climate scientist at the Indian Institute of Science in Bengaluru, is the lead researcher preparing the first national assessment of the impact of climate change in India. The country, he says, is currently unprepared.

That is the warning delivered by N H Ravindranath, the scientist who is tasked with preparing the first national study on the impacts of climate change, even as he describes how unprepared India is in terms of data and planning.

Climate change is likely to make rainfall erratic, lead to rising seas and make extreme weather events, such as droughts, floods and heat waves–like the one currently sweeping large parts of India–frequent, according to the latest report of the United Nations body to assess climate science, the Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change (IPCC).

Communities and livelihoods nationwide have already been affected by climate change, as IndiaSpend reported in a seven-part series from India’s climate-change hotspots.

Yet India, where one in every seventh person on the planet lives, has no national study on the impact of climate change, although about 600 million people are at risk from its effects.

This is set to change over the next few months of 2019. Ravindranath, a climate scientist at the Centre for Sustainable Technologies of the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) is currently heading a study that will assess the impact of climate change across regions and sectors. His assessment, which is likely to be the bedrock that will inform climate-related policy, will be submitted to the Indian government and the United Nations (UN).

Human activities have already caused warming of one degree Celsius compared to pre-industrial times, according to a 2018 IPCC report. By 2030, or latest by mid-century, global warming is likely to reach 1.5 degrees Celsius.

In March 2019, Ravindranath headed the first study that analysed climate change in India’s Himalayan Region (IHR). The study found, as IndiaSpend reported, that all 12 Indian states studied–including Assam, Mizoram and Jammu and Kashmir (J&K)–are “highly vulnerable”, with little capacity to resist or cope.

In 2018, Ravindranath, along with other researchers, also helped the government of Meghalaya assess the damage to its forests. Over 16 years to 2016, nearly half of Meghalaya’s forests experienced an “increase in disturbance”, and around a quarter are now “highly vulnerable” to the impact of climate change, the study found.

At his office at the IISc in Bengaluru, Ravindranath spoke to us on the lack of climate data by district and the need to make these data more accessible to farmers, so they can be prepared for what is coming.

Edited excerpts from the interview:

To frame a policy on climate change, India first needs to have data. Where does the country stand with respect to understanding the impact of climate change across the country?

If you want to look at the impact of climate change, say on agriculture for rice, wheat, maize, millet, pulses, so on and so forth, we still have very limited data. We need good climate models. We need good climate change projections at the district and the block level.

Now let’s take maize for instance; maize is grown in 300 districts in India. We need to run these climate models for 300 districts and see where the decline (in production) will be more or less. That kind of assessment doesn’t exist right now.

In a country like India, where agriculture is the livelihood of a majority of the people, we still do not have a detailed assessment of the impact of climate change on rice, wheat, maize, jowar, finger millet, pulses etc. We have broad studies available on the decline (in overall production).

Take the state of Meghalaya. No study will tell you what is the impact of climate change on rice production, maize, or plantation crops. There are models, but we need some data. Data [are] a problem. Climate change is all about future-based projections that are at least a decade ahead.

You never say climate-change projections for 2020. The trends are for 2020 to 2050 or 2050 to 2080. We need to run the models for different crops with soil data, water data, climate data, crop data for that particular district. That is the kind of analysis that is required, and we do not have it.

To study the changes, one would need historical data. In Sundarbans, for instance, researchers cited the lack of historical data on rainfall and wind speeds, among other variables, on the Indian side. How would you address this problem?

In case of agriculture we have some data. For forests too, there is some data. What we need is district specific data. For eg the practice of growing rice is different in Mangaluru versus Mandya in Karnataka. The way water is managed, soil is prepared – all that data needs to be fed into the models. While we have the required models, we need to get resources.

I would say right now to assess the impact of climate change at the district, block or panchayat level is still a far cry.

What kind of resources would you need to assess the impact of climate change at the panchayat level?

Right now, under the programme called national communication project, we have to assess climate change projections, impacts and adaptations, at a national level. That report has to be completed in the next six months to be submitted to the UN. There we are doing a broad national level trend. For impact of climate change on forests we are taking a national map and mapping how the forests in Kerala, Meghalaya etc have changed. We are looking broadly at districts and grids that are likely to undergo major change.

The data [are] enough to submit a report and for the government to get a broad picture of how climate change impacts the rice production or forests etc. But for actual planning, adaptation projects, development or for helping communities to cope with climate change, you need micro level data at the panchayat or at the block level.

There is no plan to prepare for that.

What does India need to do to ensure scientists have this data?

We have to conduct studies in different districts to see how rice, wheat and pulses, among others, are grown. For each crop data has to be collected from every district.

Would that require a large workforce?

Yes. Climate science is also continuously advancing and climate projections keep changing. For a country like India it is possible to have projections at the district level. There are many institutions and universities that focus on areas like agriculture and forests. The government has to identify institutions and give long-term programmes to make such studies possible.

That hasn’t happened yet.

From my reporting, I gathered that many coastal communities and farmers can already feel the impact of climate change. Do you see a sense of urgency in the government and the policy circles to do something about this?

People know that to tackle this problem (climate change), there is a need to build a network of research institutions throughout India–some in Delhi, some in Assam, some in Gujarat and so on. This networking should be done under a national programme and there is a need to focus on this issue like a mission.

We still do not have that kind of a mission approach.

What are the roadblocks?

The government needs to have a plan. Once that is done they can assess how much money is required. Then they can identify the institutions that will be a part of this network.

Do you think if the pressure comes from the people, the plan might come from the government?

Definitely, if parliament asks the government to do this, they will do it. The districts have to take decisions themselves.

There is some work happening in this area in institutions. In agriculture there is the Central Research Institute for Dryland Agriculture (CRIDA). They are doing some work but it is not at the level where it will help planning, adaptation plans and to develop coping mechanisms. The science is not good enough right now to help with the planning required for the block and district level.

In Meghalaya, the study that the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) undertook in collaboration with the state government found that the average temperature rose 0.031 degree Celsius annually for 32 years until 2012. That is a significant change. Why is it that India has not had many studies focused on the local impact of climate change by Indian researchers?

This cannot be done by all institutions. To study the impact of climate change requires modelling. The modelling capacity is not something every institution has. Very few institutions in India can do this. CRIDA in Hyderabad, Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI) in Delhi, IISc in Bengaluru and some individuals have the capacity to do this.

In the northeast there is no institution that can run these climate models. They take the help of people like us. However, it is possible to build capacity. We are trying to organize workshops on vulnerability assessment. There is a method and guidelines to do so. Based on that training from us many states in the north-east like Meghalaya, Manipur and Nagaland recently prepared vulnerability reports themselves and presented it in Delhi. Capacity building requires some effort but it is possible. The project we did was funded by the Swiss government.

While assessing the impact of climate change in a particular area it can get tricky to differentiate between human-made and natural causes. While climate change too is driven by human-made reasons, at the local level is it challenging to shift through the different stressors?

There are limitations. For example, while studying the impact of climate change on the forests, the models do not take into consideration what is the ground reality. Let’s take the Western Ghats for instance. Our model will assume that it is evergreen or deciduous throughout. The impact of climate change is different in a degraded forest or a fragmented forest versus a well maintained, healthy forest. The models are not good enough to make that distinction. The real impact on forest is based on climate and other socio-economic pressures on the forest. The same is true for the crops. We need additional work on these models.

Climate change will soon become very critical. We are not talking about the next 100 years but the next 15 to 20-year timescale. In Europe and the US there are long-term studies on how crop is changing, how pollination is changing. We don’t have such historical evidence in India for agriculture and for forests.

You mentioned your upcoming report will provide broad trends on climate change in India. How can the research go beyond that?

We need to provide access to climate projections available at a micro level to everybody at the district level in the agriculture ministry. I can (in the report) give broadly what is the trend in Karnataka but I can’t give details for Udupi, Kundapura, etc. We need to give access to all the researchers and even farmers. They should know if the rainfall has changed in the past 10-30 years so they can use it in their planning. They will keep this data in mind while building water storage structures. We need to create access to climate data. Information about different crops can be uploaded on the website. Some research institute in Mangalore or Coimbatore wants to use the data, they should have access to it. Not everyone needs to run a model. They can be given access to this data directly.

Within the scientific community, is there a push for interdisciplinary research to study climate change and public health links, for instance?

The kind of networking, team work and long-term planning needed to tackle climate change doesn’t exist.

The National Innovations in Climate Resilient Agriculture (NICRA) is one of the good projects. They have some good work but they too will have to intensify their work. There is nothing in terms of research on the impact of climate change on health, forests and infrastructure. Climate change will impact the railways, dams, coasts, ports and all the structures. Everything will be affected.

In the next five years, how should the government respond to climate change?

The government should have a plan for each sector like agriculture, forests, health and infrastructure. For each of these sectors we have to identify institutions, have a network and give a long-term mandate.

There is a need to identify the key sectors and then to identify key institutions who will oversee the project. The network built should be provided enough resources to continue the work.

(Shetty is a reporting fellow at IndiaSpend.)

Courtesy: India Spend