Baloda Bazar, Kabirdham (Kawardha), Rajnandgaon, Mahasamund, Kanker (Chhattisgarh): “I’ll ask them to give me a job first and then think about giving my vote,” said 28-year-old Kekti Verma, holding back her tears. “I have three girls, the eldest one is 10 and youngest four. I haven’t got any help till date from the government.” Kekti is the widow of Dhal Singh Verma, a two-acre paddy farmer in Sararidih in Baloda Bazar constituency, 50 km northeast of Chhattisgarh’s capital, Raipur.

Kekti Verma with two of her three daughters. She is yet to receive any help from the government since her husband Dhal Singh Verma, a farmer, committed suicide in 2017 in Sararidih, Chhattisgarh. He had a loan of Rs 600,000.

Unable to repay a Rs 600,000 loan, Dhal Singh hung himself from a mango tree in a nearby farm on October 6, 2017. He was 30 years old.

As many as 1,344 farmers–519 a year or, more than one per day–committed suicide in Chhattisgarh during the last two-and-a-half years till October 30, 2017, The Hindu BusinessLine reported on December 21, 2017. Baloda Bazar reported 210 farmer suicides, second highest in the state. IndiaSpend could not independently verify these data.

This number is similar to the number of farmers/cultivators who committed suicide in 2016–as IndiaSpend reported on March 21, 2018, based on a government response in parliament that month. The state contributed 9% of the 6,351 farmer suicides in India that year, fifth most in the country.

As Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) longest serving chief minister, Raman Singh, 66, tries to win a fourth consecutive term in a state with nearly 4.3 million farmers–the state is 77% rural and 17% of the state gross domestic product comes from agriculture–our reporting shows he will face issues such as farmer suicides, discontent due to inadequate government purchase price for foodgrains, delays in the payment of Rs 300 per quintal (100 kilograms make a quintal) of paddy bonus promised before the last election, and inefficient crop insurance under the Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana or PMFBY (Prime Minister’s Farm Insurance Scheme).

Despite despair and unrest roiling the state’s farms, a Lokniti-CSDS-ABP News pre-election survey, conducted in October 2018, indicated 42% of the farmers planned to vote for the BJP, while 36% would vote for the Congress party. An average of four opinion polls indicated a close contest between the two parties with 45 seats going to the BJP, compared to 38 seats for the Congress in the 90-seat legislative assembly, BloombergQuint reported on November 8, 2018.

Why farming is important

IndiaSpend travelled to five districts–Balodabazar, Kabirdham, Rajnandgaon, Mahasamund, Kanker–in the Chhattisgarh plains to understand the concerns of farmers as the state goes to polls in two phases: November 12 and November 20. These are five of 15 districts in the plains that constitute nearly 69% of the 4.8 million hectares–equivalent to the size of Haryana–of net sown area in the state.

Chhattisgarh, also known as the rice bowl of the country, has set a target to produce 8.2 million tonnes of paddy in kharif (monsoon crop) 2017, and was among the top three rice-contributing states in 2016, the Business Standard reported on June 26, 2017.

As we said, nearly 70% of 25.5 million people in the state are engaged in agriculture, according to the website of the directorate of agriculture. Of these, 46% are small and marginal land holdings (below 0.5 hectares to less than 2 hectares), according to the 2015-16 agriculture census.

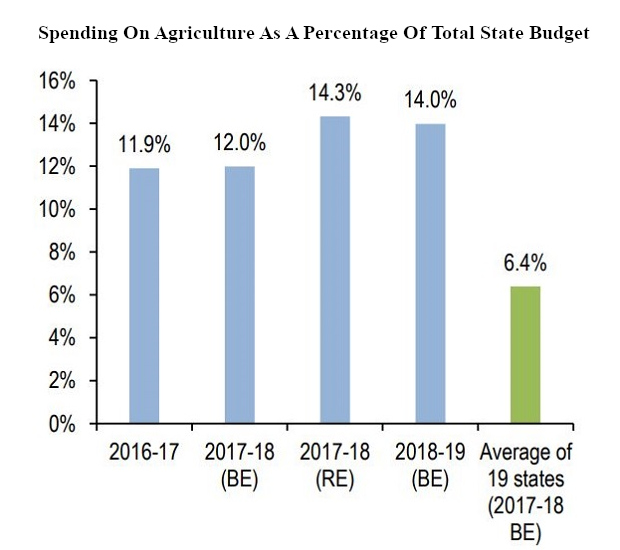

In an election year budget to woo farmers, the BJP government allocated 14% of its total budget (Rs 83,179 crore) towards agriculture and allied activities, higher than the budgets of 18 other states (average of 6.4%), as per analysis from PRS Legislative Research, a research organisation. This budget was also slightly higher than the 12% allocated by Chhattisgarh in 2017-18.

Source: PRS Legislative Research

Note: 2017-18 (BE), 2017-18 (RE), and 2018-19 (BE) figures are for Chhattisgarh

In elections since 2003, the BJP’s seat share was roughly 55%, while the Congress’ was 13 percentage points lower, at 42%, on average, in a 90-seat assembly representing 27 districts.

Inadequate government support price, delayed bonus, and protests

Swades Tikam, 50, is a member of the zila kisan sangh (district farmers union), and is in the thick of the farmer agitation against the government.

Swadesh Tikam, a farmer leader in CM Raman Singh’s constituency of Rajnandgaon in Chhattisgarh, said farmers are unhappy with the government’s policies and there have been nearly 100 farmer protests since the last election.

On September 18, 2017, he and few others were arrested from their homes in the wee hours of the morning and jailed in the neighbouring district of Durg. They, along with other farmer groups across the state, were planning a state-wide protest march the next day demanding a farm loan waiver, and the paddy bonus promised by the BJP in its 2013 assembly election manifesto.

“I have been arrested during protests before, but being arrested from my home was a first for me,” he said tightening a cloth tied like a turban around his head. “We must have had 100 protests since 2013, I think. This government does not want to negotiate terms with farmers and we want it replaced. We’ll support any other party that can show the work it has done for farmers.”

Tikam has a 9-acre paddy farm that his friends help cultivate since he is, often, busy mobilising farmers. “Income from farming has been inadequate. I moved from paddy to vegetables hoping to earn a better income. But soon realised that at the mandi (farm produce market) the commission agents were exploitative and the prices low. So I moved back to growing paddy.”

An acre provides him around 13 quintals of rice. If the rains are good and irrigation sufficient, there is an extra seven to 10 quintals. Each acre incurs an input cost of Rs 20,000, he said, which includes seed, fertilisers, labour etc. But with the vagaries of the weather and the low purchase price, even recovering the investment becomes a challenge, he said.

The median monthly per capita expenditure–monthly expense–for Indian farm households was Rs 1,375, indicating that 50% of the households spent less than that per person per month, IndiaSpend reported on September 24, 2018.

“Each day there are hundreds of people riding into Rajnandgaon town on their cycles with their lunch boxes. Almost all of them are farmers looking for work because farming alone will not help run a household,” said Tikam.

Around 100 km away in Kanker district of Bastar division, two paddy farmers, Manish Sinha (40) and Domendra Sahu (32), concur with Tikam. Despite having eight and three acres of land, respectively, Sinha runs a small restaurant and Sahu does electrical work and other odd jobs to make ends meet.

Sinha, in addition to the 8 acres in his village in Nandanmara, has leased five more to grow paddy. The lease arrangement requires him to part with a share of the produce with the farm owner. “I get around 20 quintals of paddy for an acre. I am able to make around Rs 4,000 off it after paying out all costs,” said Sinha. “Hiring a tractor costs Rs 1,000 an hour, labour is around 180 to 200 for the day per person, and I have a Rs 40,000 loan in the cooperative this kharif (monsoon) crop season. I will be lucky if I recover input costs.”

In addition, a new borewell would cost Rs 100,000 or Sinha would have to buy water from other farmers. Though elections are around the corner, we do not think much is going to change even if the party in power changes, both Sinha and Sahu said.

Sinha received a paddy bonus of Rs 18,000 for 60 quintals for 2016 and 2017, but is yet to receive any for 2013 and 2014. The Chhattisgarh legislative assembly passed the supplementary budget to spend Rs 2,400 crore for paying bonus to farmers in 2018 against paddy procurement and benefit nearly 1.3 million farmers registered with primary cooperatives of the state-run Chhattisgarh Marketing Federation, Business Standard reported on September 12, 2018. The bonus provides additional income above the procurement price.

“Farmers know that the 2018 paddy bonus will be made because of the elections and the BJP needs votes. Let’s see if the 2014 and 2015 bonuses are provided,” said Tikam.

The government declared it will buy 15 quintals of rice per acre, compared with 25 quintals in the previous year, the Financial Express reported on January 17, 2015. Farmers sell any produce above the 15 quintals to private traders who are likely to pay a price lower than the government’s.

In July 2018, the government purchase price for common paddy was increased by 13% to Rs 1,750, and for Grade A rice by 11% to Rs 1,770, but farmers said it was inadequate to sustain the trade.

“In 2013, the BJP manifesto stated that they would request the union government to increase the government purchase price to Rs 2,100 per quintal for paddy and provide a paddy bonus, effectively providing Rs 2,400 a quintal for farmers,” said Tikam. “Even this has not happened, while farmers on an average want it to be at least Rs 2,500 a quintal of paddy.”

Meaningless crop insurance

Ghanshyam Diwan has been trying to get his 20-acre paddy farm assessed by the patwari (village accountant) to claim insurance under PMFBY–the government’s crop insurance program–in Mokha, Mahasamund district, about 100 km east of Raipur. Part of his crop was affected by Maho, a pest commonly found on paddy farms. “This is happening for the first time to me, and it is spreading across the farm,” he said. He may have to spend close to Rs 4,000 an acre to fight the pest or simply lose all the produce.

Ghanshyam Diwan’s 20-acre paddy farm has been affected by Maho, a pest. He is trying to get a survey done to assess the loss to claim insurance under PMFBY.

Another farmer, Daniram Dhruv, who has a 2-acre paddy farm, received Rs 40 from an insurance claim from the PMFBY in 2017. Even his son, Prem Dhruv, who is a chairperson of the cooperative, did not know how the local survey for insurance came up with the Rs 40 figure. Prem was unable to share data on the insurance claims because of ongoing technical updates to his system, he told IndiaSpend.

A number of farmers from across the country have also made allegations that money is being deducted from their accounts and they are being enrolled for PMFBY without prior information, The Wire reported on March 31, 2017. This is because farmers in the notified area who possess a crop loan account/kisan credit card account (called as loanee farmers) to whom credit limit is sanctioned/renewed for the notified crop during the crop season would need compulsory coverage, the PMFBY guideline says.

One of the objectives of the PMFBY is to “provide insurance coverage and financial support to the farmers in the event of failure of any of the notified crop as a result of natural calamities, pests & diseases”, according to this PMFBY guideline.

For the kharif or monsoon crop in 2016, about 1.4 million farmers were insured under PMFBY and the Restructured Weather Based Crop Insurance Scheme (RWBCIS)–insurance against weather-based calamities like rainfall, drought, humidity etc. Nearly 6% of these farmers benefited, as per government data. In the 2017 kharif season, the number of farmers who benefited increased 36 percentage points to 43%, although the total farmers insured fell by 7% to 1.3 million.

| PMFBY And RWBCIS For Kharif 2016 & 2017 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | State | Farmers Insured (In Million) | Area Insured (In million ha) | Sum Insured (In Rs Crore) | Farmers Premium | State | GOI | Gross Premium | Claim Paid | Farmers Benefitted (In Million) |

| 2016 | Chhattisgarh | 1.4 | 2.2 | 6681 | 127 | 72 | 72 | 271 | 133 | 0.09 |

| All India | 40 | 37 | 131117 | 2918 | 6764 | 6592 | 16275 | 10424 | 25 | |

| 2017 | Chhattisgarh | 1.3 | 1.9 | 6546 | 128 | 89 | 89 | 306 | 1303 | 0.56 |

| All India | 40 | 37 | 131117 | 2918 | 6764 | 6592 | 16275 | 10424 | 12 | |

Source: Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (data till October 2018)

The Chhattisgarh government declared 96 tehsils (an administrative area) from 21 districts drought-hit, after receiving assessment reports from district collectors, The Indian Express reported on September 12, 2017. “The government has disbursed Rs 5.46 billion [Rs 546 crore] to the districts for immediate relief and Rs 3.30 billion [Rs 330 crore] had been distributed so far,” said Prem Prakash Pandey, state revenue minister, Business Standard reported on September 15, 2017.

But in Baturakacchar village of Kawardha, a drought-affected village, 32-year-old Jeevan Yadav, a sugarcane and paddy farmer and block president of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS)-affiliated Bharatiya Kisan Sangh (BKS), did not receive any relief in 2017. He has 12 acres of sugarcane and four of paddy out of which around 10 acres dried because of the drought, he said.

“Of the 16 villages under the cooperative society which my village falls in, only one got any drought relief from the government,” said Yadav.

The assessment for farm insurance is based on an average estimate made by the agriculture department, explained Doman Chandravanshi, district secretary of BKS, who has a 60-acre farm, where he grows sugarcane and paddy, in Patharra panchayat in Kawardha. The claim is considered if the crop production falls below the estimate. Further, in order to be eligible for insurance, farmers in a panchayat must have at least 15 hectares of land of the notified crop.

In Kawardha, the average is seven quintals an acre for paddy. With the quality of seeds and fertilizers, even scanty rainfall provides more than that quantity which means that, in most cases, a claim for crop loss cannot be made. “This means that despite incurring a loss, insurance is meaningless,” said Chandravanshi.

The assessment is based on a seven-year average yield or threshold yield for a notified area, said D.K. Mishra, joint director, agriculture in Chhattisgarh. “The actual yield is based on four crop cuttings in a season taken at the panchayat level. If there is a calamity, the actual yield is subtracted from the threshold yield average,” he said.

Further “farmers would have taken loan for only certain amount of land for which insurance would have been provided”, said Vishal Kharbade, regional manager of the Agriculture Crop Insurance Company, a public sector crop insurance company, in Raipur. “If they grow multiple crops, a calamity need not necessarily affect all crops. Sometimes farmer may not know about these details.”

Jeevan Yadav (extreme right) and Doman Chandravanshi (centre) are members of the RSS-affiliated Bharatiya Kisan Sangh in Kawardha. Party affiliations do not matter when it comes to farm distress, they say. There have been over 20 protests since the last elections.

Farmers are also impacted by market forces. When sugarcane produced is in excess of the sugar factories’ demand, farmers are forced to sell to to jaggery-making units at throwaway prices. Last year, some farmers sold at a price as low as Rs 80 a quintal, Yadav said. Sugarcane is not procured by the government.

Yadav spent around Rs 35,000 to Rs 40,000 an acre on sugarcane for seed, water, fertilizer, labour and transportation. He had an income of Rs 91,000 in 2017.

Their affiliation to the RSS has not stopped Yadav’s farmers union from agitating against the BJP government. We’ve had more than 20 protests since 2013, he said.

“In 2015, nearly 10,000 farmers here protested for the Rs 50 bonus and transportation cost for sugarcane, which had been stopped,” said Chandravanshi, district secretary of BKS. “We do not look at party affiliations on matters of farm distress.”

For Chandravanshi and Yadav, farm distress is a major election issue but they were non-committal on which party they would vote for.

Cycle of debt and suicide

According to the state’s agriculture and cooperative department officials, 71% of the Rs 4,474.15 crore disbursed to the farmers was repaid between July 1, 2016, and May 31, 2017, the Business Standard reported on June 26, 2017.

But this does not take into account the money that farmers borrow from informal moneylenders at high interest rates.

Gajendra Singh Koshle, 28, a bachelor of science graduate, and farmer in Arang village in Raipur district, has taken a loan of about Rs 26 lakh, partly for his father’s treatment, in 2013. These include loans taken by his father from the agricultural cooperative, a tractor loan from a bank, informal loans for the farm, his and his siblings’ weddings and demonetisation, he said. Koshle, who owns 10 acres of land and has leased another 15, is part of the farmers’ movement against the government’s agriculture policy.

Gajendra Singh Koshle in Arang in Raipur district has a Rs 26 lakh loan for his paddy farm. His loans include those taken for weddings, buying a tractor, and repaying existing loans.

In 2015, a variety of paddy that he had hoped would provide income failed due to the drought. His winter crop was affected by Maho for which he did not get insurance relief. Further, he wasn’t paid the paddy bonus for the paddy procured for the kharif season, and the inadequate procurement price for paddy made things worse.

“I decided to sell my land to repay some of the debt. But by the time I negotiated the terms with the buyer, demonetisation hit and they backed out,” he said. “My loan from the moneylender was at an interest rate of 5% per month. The stress on repayment is high.”

In Mokha village in Mahasamund, 60-year-old Manthir Singh Dhruv’s Rs 600,000 loan burden forced him commit suicide by hanging himself to a tree in August 2017. “He had loan from banks and the cooperative, but the drought and delays in bonus made it difficult,” said Mohan, Manthir’s 29-year-old son. He had also dug a borewell for nearly Rs 70,000 for his seven-acre paddy farm.

The government has not provided any compensation since his father, Manthir Singh Dhruv committed suicide, says Mohan Dhruv of Mogha in Mahasamund. He received Rs 50,000 from the Congress, he added.

“We’ve received around Rs 50,000 from the Congress party but nothing from the state, even though I have a government order requesting me to submit documentation for compensation,” said Mohan, showing the order in his possession. He will not vote for the government.

In Kawardha, the family of farmer Santosh Sahu, who committed suicide by consuming sleeping pills in July 2017, is upset. “My father’s suicide and the government’s indifference will be a factor for my vote,” Vikas Sahu (21) told IndiaSpend at his home in Dehri village. Santosh had a loan of around Rs 15 lakh, including that for a new jaggery-making unit he had set up.

Vikas Sahu, 21, was promised a job in the police department by the politicians when his farmer father, Santosh Sahu, committed suicide in Dehri village of Kawardha. But the promise was not fulfilled, he said.

“We still have bank officials asking for repayment. The member of the legislative assembly visited us, and the government promised to employ me in the police force, but nothing has happened since,” said Vikas, who shares the home with 18 other members, including his mother, brother, and uncles. About 2 acres of Santosh’s land is with moneylenders.

‘Farming isn’t being considered an economic activity’

“The issue is that agriculture is not being seen as an economic activity,” Devinder Sharma, an agriculture expert, told IndiaSpend. “If you make agriculture unproductive and non-remunerative, people will move out of farming. Successive governments have been following this policy.”

Farmers want an assured income and so they are not moving from paddy as governments procure it, he said.

Both the central government and the state government have a role to play in improving agricultural policies. As farmers reel under the impact of low income and bad loans, experts believe that just announcing government procurement prices isn’t enough, but any procurement policy also needs to be implemented well.

“The minimum support price (MSP or government purchase price) regime must not just be a declaration of prices, but should also be backed by effective procurement,” said Sukhpal Singh, professor at the Centre for Management in Agriculture at the Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad (IIM-A). “There is no meaning in talking about MSP if it isn’t implemented in terms of procurement, which is now restricted to a few crops and a few states.” Chhattisgarh is doing well in terms of procurement and using it for public distribution system, he noted.

He is also concerned about the PMFBY. There are issues of awareness, delays in payment, and the assessment for insurance is done only at the block or village/panchayat level which does not help individual farmers affected. Although the premium paid by the government is high, the programme has been of limited use to farmers, as proper information is not shared with farmers about how the claim is assessed, and the process to claim benefit, said Singh.

IndiaSpend sent an email and a reminder for comment to Radha Mohan Singh, minister of agriculture and farmer welfare, and the secretary to the ministry. This story will be updated as and when they respond.

Further, experts are concerned about the unstainable model of farming in the state. “Chhattisgarh must not follow the Punjab farming model” which is water intensive, with high use of pesticides, and farm indebtedness. “It has an opportunity to create an ecologically sustainable model for agriculture which includes forestry,” said Sharma.

Given the present circumstances, doubling of farm income by 2022 can happen only on paper, he noted.

In Baloda Bazar, a district dotted with seven cement factories that have also acquired farmland for mining, Kekti, whose husband committed suicide because of the loan burden, makes around Rs 100 a day from farm labour. “I have enrolled to finish my 12th standard and want to work for my girls,” she said.

(Paliath is an analyst with IndiaSpend.)

Courtesy: India Spend