Rajahmundry (East Godavari district), Andhra Pradesh: The most significant difference between Ushasri’s two sons–born seven years apart–was their weight.

Ushasri with her three-month-old son and anganwadi worker T Vijaya. Ushashri’s first son was 2.5 kg at birth, while her younger son was 3 kg, apparently heavier because she was better fed.

The first was 2.5 kg, just above the low birth-weight category, which is linked to long-term health risks, as a fifth of Indian babies are, as are 17.6% in Andhra Pradesh (AP). Ushashri’s second son, born here three months ago, 150 km north of Vijayawada, was a healthy 3 kg.

What changed during her two pregnancies was the universalisation of an AP government programme that began in 2013 in 102 so-called “high risk” blocks to all 676 blocks in 2017 to provide a hot, cooked meal of rice, sambar, milk and eggs to nearly 600,000 pregnant and lactating mothers at local anganwadis or government day-care centres.

Before the programme, YSR Amrutha Hastham–earlier known as Anna Amrutha Hastham and Indiramma Amrutha Hastham–the state provided pregnant and lactating mothers with raw rice, dal, vegetable oil and four eggs at home.

“Now, I eat (cooked food) at the anganwadi,” said Ushasri, dressed in a pink kurta and salwar, her wet hair wrapped in a towel, as she spoke to a visiting anganwadi worker and four visitors at her home in Aryapuram, a Rajahmundry suburb.

“Both ways [of giving food] are fine–but this is better,” said Ushasri, who is a graduate and takes tuition classes at home. Her husband works in a private company and their monthly income is Rs 6,000, above erstwhile undivided AP’s urban poverty line of Rs 1,009. Her only complaint: eating an egg is difficult because she is a vegetarian. At the anganwadi, health workers have told her the egg is good for her.

“I have the rice and milk, but the egg is a little difficult,” said Ushasri.

There have not been many independent assessments of YSR Amrutha Hastham, and the benefit of such feeding programmes is contested–as we explain later–but a limited 2019 evaluation by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) found that it satisfied mothers, boosted their dietary diversity to 57-59%, egg and milk consumption to 74-96% and calcium intake through tablets to 87%.

Our check of the AP programme confirmed some benefits and found logistical shortcomings related to unpaid anganwadi rents and staff salaries and staff shortages. But the data from the UNICEF evaluation have implications for AP’s and India’s future.

Undernourished children: India’s lost opportunity

With over 48 million children malnourished and two of every five Indian children stunted, or short for age, India has the highest number of undernourished children in the world.

For most children, the problem starts before they are born.

Children who received extra nutrition through government-run programmes from the time they were in their mothers’ wombs until age three were 11% more likely to acquire a graduate degree than those who received them between ages three and six, according to a January 2018 study published in the Journal of Nutrition.

Children eat hot meals at the Kothalanka anganwadi centre in Andhra Pradesh’s East Godavari district.

The study offered conclusive evidence that adequate nourishment to unborn babies and infants creates benefits that enhance their education and employment prospects in later life.

With the education benefit of early-life nutrition extending to college, the researchers estimated that such daily exposure could potentially increase India’s college graduates from 7.5% of the country’s 73.8 million Indians aged 20 to 24 to 11.8%. An increase in the college graduation rate, in turn, would deliver economic gains from higher wages.

This would be a significant economic achievement for a country with one in three of the world’s 156 million stunted children under five. In 2016, it was estimated that undernourishment among India’s children under five years would cost $37.9 billion–Rs 27,240 crore or about as much as India’s 2019-20 budget for the National Rural Health Mission–in future, through lost schooling and economic productivity.

YSR Amrutha Hastham is one of five state programmes that aim to reverse current nutrition trends. Healthy children are a prerequisite to take advantage of India’s demographic dividend, the economic benefits of having the world’s second largest working population, which is now in danger, as IndiaSpend reported in August 2019.

Getting to know what’s best for baby

“I breastfed my son within an hour of his birth,” said Ushasri. “At the anganwadi, they explained to me that I have to breastfeed up to six months. So, I am not giving him anything else–like water or other milk.”

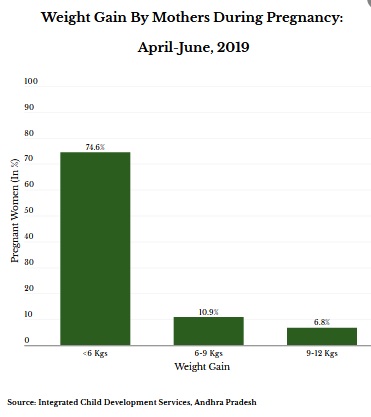

The result of the fresh, nutritious meals was that Ushasri gained 12 kg during her second pregnancy, and her second son is healthy.

Most Indian mothers enter pregnancy with poor nutrition: 23% of reproductive-age women are too thin for their height and 58% of pregnant women are anaemic, increasing the risk of death for them and their babies. Additionally, 8% of pregnant women–approximately 4.5 million–are adolescents, according to the National Family Health Survey (2015-16).

This is why improving the nutritional status of mothers is important.

Only 46% of pregnant women and 51% of lactating mothers nationwide received supplementary nutrition services from anganwadi centres under India’s flagship 44-year-old scheme for maternal and child health, the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS), the world’s largest such effort.

The average birth-weight of children whose mothers are enrolled in the YSR Amrutha Hastham was 2.9 kg in 2019–babies above 2.5 kg are termed normal weight babies. There were about 300,000 each pregnant and lactating mothers enrolled in financial year 2019-20.

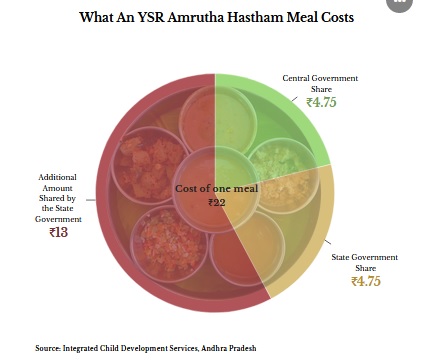

The programme in AP runs under the ICDS and the supplementary nutrition programme, with a budget of Rs 2,219 crore, with the state government putting in Rs 17.75 to the central government’s share of Rs 4.75 for each meal.

Five states–Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Chhattisgarh and Maharashtra–in India offer mothers some form of hot cooked meals in their anganwadi centres. Two states, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, have discontinued the programme, and Odisha is about to begin the programme.

Since the hot-cooked-meals-for-mothers programme replaced take-home rations (THR)–fortified supplementary nutrition for children under six and lactating and pregnant mothers for home use–traditionally distributed by the AP government, experts said it is important to assess the performance of the hot-cooked-meals programme against THR.

In early August 2019, we travelled to urban, rural and tribal areas of AP’s East Godavari district and found widespread acceptance of the hot-cooked-meals programme and satisfaction among beneficiaries. We also found that anganwadi workers who implemented the scheme needed more support from the government and better infrastructure.

More dietary diversity, limited weight gain

While the supplementary nutrition programme already supplied raw rations to mothers, the rationale behind a hot meal at the anganwadi is to ensure the mother consumes the meal (and not someone else at home), receives antenatal services and other nutrition support, such as iron and folic supplements, calcium tablets, deworming tablets and health information.

A hot, cooked meal is served to pregnant and lactating mothers at the Kothlanka anganwadi centre in East Godavari district of Andhra Pradesh.

In AP’s YSR Amrutha Hastham, the hot, cooked meal is served six days a week between 11 am and 2 pm to pregnant and lactating mothers, prepared by anganwadi workers who also prepare it for children who come there in the morning. In addition to what the supplementary nutrition programme provided at home, the state has added on an egg and 200 ml of milk every day.

Anganwadi workers are expected to keep a record, through a mobile application, of women enrolled in the programme, the services they received, weight gained during pregnancy and birth-weight of the babies.

The 2019 UNICEF evaluation we referred to was carried out in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, based on interviews with 360 pregnant and lactating mothers and a review of data from the state government’s management information system. It also found:

- While on-the-spot consumption of iron folic acid tablets was “poor” (22.6%) because most respondents took the tablets at home (77%), 87% of mothers took calcium and 56% deworming tablets.

- Most beneficiaries consumed the meal on 21 out of 25 days in a month.

- The estimated mean weight gain between the second and the ninth month of pregnancy ranged from 8.3 to 9.7 kg

Malnutrition among women was greater in tribal areas as compared to rural areas, according to the evaluation: 19% were wasted compared to 12% in rural areas, and 79% of tribal women using the programme had the minimum nutritional diversity compared to 89% in other rural areas.

While most respondents found the food tasty and the quantity sufficient in the evaluation, most enrolled mothers gained less than 6 kg, while only 6.8% gained more than 9 kg, according to the latest data provided by the state government.

This is within India’s average maternal weight gain–5.1 kg to 8.3 kg but below the global average–8.3 kg to 15.3 kg.

The average weight of the baby born to the women enrolled (between January and July 2019) was 2.9 kg, according to government data, which is within the average birth-weight (2.8 to 3 kg) in India.

In deprived tribal areas, most enthusiasm

Surrounded by verdant hills and paddy fields, Devarapalle is a small tribal village in Maredumilli mandal of East Godavari district. The Devarapalle anganwadi was destroyed in a flood and classes are held in a community centre. There is no toilet or kitchen.

The position of a helper has not been filled for many years and anganwadi worker Ganga Bhawari, 29, does the cooking as well. “There is no anganwadi building, no compound, no power and no water supply,” she said. A teaching assistant, recruited by a nonprofit, who works with children, helps Bhawari.

Loeshwari, 21, is a mother of two–a three-year-old and seven-month-old. The meal she ate at the anganwadi was invaluable, says Loeshwari, who got an egg, milk, sambar and rice. “We can’t afford to eat an egg every day,” she said.

At the Devarapalle anganwadi, we met Loeshwari, 21, a mother of two–a three-year-old and seven-month-old–who looked much younger because she was thin and small. She weighs about 42 kg, and came to the anganwadi every day during pregnancy and till her second child was six months old.

The meal she ate at the anganwadi was invaluable, said Loeshwari. “We can’t afford to eat egg every day,” she said. Tribal communities do not milk their cows, so mothers had limited access to protein.

Life is tough for women here, they have three to five children, work through pregnancy, and they do not go to their maternal homes for delivery–as many in India do–so mothers are back to household chores immediately after birth.

There are two additional programmes for women and children in tribal areas: while anganwadi centres statewide feed children aged three to six, those in tribal areas feed children six months onwards. Lactating mothers receive additional packet of dates, jaggery and peanut chikki–a kind of candy–and ragi malt to improve nutrition.

“Two of my children come to the centre, eat and like the meals,” said Kadavala Sugunavati, 26. “My children fall sick less often since they started the meals.”

There are five pregnant women, three lactating mothers and 33 children, aged seven months to seven years, registered at the Devarapalle anganwadi. Almost all come by for their daily meal.

“Some women come early in the morning, when they leave for work, for eggs and milk, the rest come in the afternoon for rice and sambar,” said Ganga Bhawari, the anganwadi worker.

This enthusiasm was evident in other rural centres we visited, but it was not in urban anganwadis.

More gripes in urban areas

At the Lishbarpeta municipality primary school in Aryapuram, two anganwadi centres have been merged. More than 30 children below six were studying in the classroom, and two anganwadi workers and two helpers were cooking the meals. However, out of the six pregnant and four lactating mothers registered here, only two or three come to the centre every day.

Pregnant and lactating mothers being counselled by child development project officer C H V Narsamma at Lishbarpeta Municipal School, Rajahmundry in Andhra Pradesh’s East Godavari district.

“They say that it is too far off to travel, and there are flights of stairs to climb up and down, which they find difficult,” said anganwadi worker Vijaya. Many mothers prefer their meals to be packed and brought to them by their family members which they eat at home.

“It takes me a whole hour to come here to have the meal and I have a young baby at home and another child,” said a mother who had visited the centre to have the meal that day on the request of the anganwadi worker.

“Beneficiaries feel that it is free food, why to go and eat at the [anganwadi] centre,” said D Sukhajeevan Babu, project director for the ICDS in East Godavari district. He said at least 10-20% of women do not show up for the meals.

“There should be a flexibility (offered) for mothers between getting take-home ration and hot meals,” said Babu.

Does the evidence support hot, cooked meals?

Not everyone is convinced of the benefits of “spot-feeding programmes”, such as YSR Amrutha Hastham.

While maternal malnutrition–a mother’s height, body mass index and anaemia–is a risk factor for poor child outcomes, the impact of one hot-cooked daily meal on child health or other supplementary foods on maternal diets is not evident, said Purnima Menon, senior research fellow, International Food Policy Research Institute.

“That said, I understand that these programmes also include additional inputs at the time of the meals–provision of iron tablets and behaviour change communications,” said Menon. “This is good, but it also makes it challenging to disentangle the effects of the meals per se from the other components offered alongside.”

Menon had two other reservations:

- While programmes such as the YSR Amrutha Hastham may benefit mothers who attend, evidence has shown centre-based feeding programmes exclude those who cannot attend every day.

- Feeding programmes for pregnant mothers who are already calorie-sufficient may lead to excess weight gain and retention after pregnancy, which is a concern for southern states.

Other experts have said there is enough evidence to support spot-feeding programmes.

The risk of stillborn babies was significantly reduced for women given balanced energy and protein supplementation, according to a 2015 review of several studies. Other reviews and studies (here, here and here) found a significant increase in the mean birth-weight of new-born infants whose mothers were provided nutritional supplements during pregnancy, wrote Prasanta Tripathy, public health researcher and activist and co-founder of Ekjut, a non-profit working in Keonjhar, Odisha in an email response.

Governments should invest in addressing the intergenerational cycle of undernutrition in the first 1,000 days of birth, said Tripathy. States should map “food-insecure regions” and target them with not just supplementary nutrition but also to other determinants of undernutrition, such as drinking water, he said.

Venkat Laxmi, 28, with her seven-month-old son, who was a healthy 3 kg at birth. She is a beneficiary of the Andhra Pradesh government’s hot, cooked meal programme, which offers this meal for 25 days a month.

Without adequate human resources and infrastructure, even the best schemes cannot reach their potential, said experts. While the AP government has been committed to run the YSR Amrutha Hastham, there are some obvious gaps relating to unpaid salaries, rent and staff shortages.

Every anganwadi worker we spoke to admitted to getting her salary after a delay of two to four months. Since many of the anganwadi centres are not in government buildings, rent for some centres had not paid for the last six months. Many anganwadi workers paid for the cost of running the centre from their own pockets. Vacancies at every level affect the efficiency of the programme: the anganwadi in Devarapalle did not have an anganwadi helper; there is 8% vacancy in anganwadi helpers, 23% vacancies in supervisors in the district, government records show.

The vacancy in supervisors affects the effective monitoring of the services. Many centres we went to had weighing scales that were not working.

On the larger front, there are concerns that the most vulnerable mothers may have been left out of the scheme as the percentage of food-insecure beneficiaires in the scheme was much lower than expected, said the UNICEFevaluation.

This report has been supported by ROSHNI-Centre of Women Collectives Led Social Action.

This story was first published here on Healthcheck.

(Yadavar is a special correspondent with IndiaSpend.)

Courtesy: India Spend