Gillette’s ‘The best a man can be’ advertisement has dared to be different in how it speaks to its male audience. Gillette

Viewed more than 23 million times on YouTube, the advert has so far attracted more than 330,000 comments, about 650,000 likes and 1.1 million dislikes. No advertising campaign challenging stereotypes about girls and women has ever been this controversial.

Gillette’s ‘We Believe: the best a man can be’ advertisement.

Perhaps that is because those adverts have tended to celebrate an “empowered” view of girls and women. There is even a term to describe this type of advertising with pro-female messages – femvertising – that has its own dedicated awards.

Challenging gender stereotypes of men, on the other hand, is proving less straightforward.

Other campaigns that have explored modern versions of masculinity have taken a similar approach to femvertising. But Gillette’s new advertisement is different. It uncompromisingly confronts problems such as sexism, bullying and harassment associated with toxic masculinity. As a result some perceive it as negative – a denunciation as opposed to a celebration of boys and men.

It exemplifies a significant creative challenge for advertisers at a watershed moment in the movement for gender equality. How do you celebrate masculinity without acknowledging toxic masculinity in this time of #metoo?

Gender stereotypes in advertising

My research examines sexist advertising practice and how this more broadly contributes to gendered inequalities. For example, how advertisements that glorify the violent exploitation of women work to normalise violence against women.

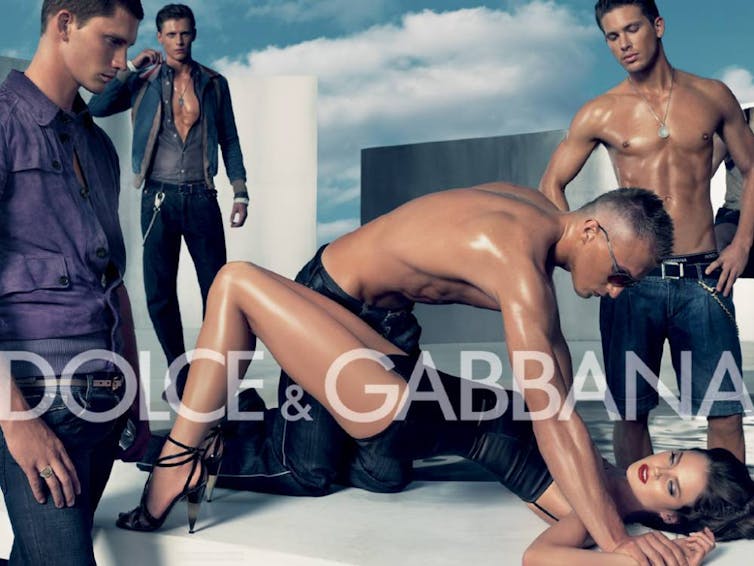

Fashion house Dolce & Gabbana’s 2007 spring/summer advertising campaign was criticised for simulating a gang rape scene. Supplied

Gender stereotypes are another form of sexist advertising practice.

Because advertisements must simply and persuasively communicate a message that can be understood by a relatively broad audience, the industry has long been susceptible to perpetuating stereotypes – oversimplified ideas of the way people should be.

Recall how television program Masterchef promoted its 2013 series as a “battle of the sexes”. The women wore pink and men blue. They trash-talked one another with a litany of stereotypes: “men are more experimental!”, “women can multitask!”.

Critically, most creative work in agencies has historically been led and shaped by men using hypermasculinity as a model for creativity. One study has likened agency cultures to locker rooms – intensely competitive, structured by male bonding and rife with sexual harassment and gender-based discrimination. As a result few women have been able to break into and succeed as creatives in advertising.

But this has begun to change, and the industry has started to face up to the problematic way in which advertising has reinforced gender stereotypes. There is increasing resistance to portrayals suggesting a single way to be a man or woman.

Last year the World Federation of Advertisers launched guidelines for progressive gender portrayals in advertising, namely unstereotyping ads, that highlights the importance of diverse teams and gender aware cultures. The Australian Association of National Advertisers (AANA) updated its Code of Ethics to state that gender-stereotypical roles and characteristics, such as a man doing DIY, must not suggest these are always associated with or carried out by that gender.

Gillette’s parent company Procter & Gamble, along with other multinationals heavily invested in gender-based marketing, has joined the Unstereotype Alliance, a United Nations-backed initiative to eradicate harmful gender-based stereotypes in advertising. Alliance members commit to creating content that depicts people as empowered actors, refraining from objectifying people and portraying progressive and multi-dimensional personalities.

Challenging toxic masculinity

Toxic masculinity refers to norms and ideals of manhood that are both constraining and harmful. It fosters rigid expectations that boys and men should be dominant, aggressive, stoic and devoid of emotion. It is instilled by telling boys to “toughen up” because “boys don’t cry”. It is contemptuous of men “acting like girls”. It is harmful to both men and women.

The director of Gillette’s new advertisement, Australian-born Kim Gehrig, is no stranger to this territory. Her short film You Think You’re a Man explores the cultural expectations of what it means to “be a man” in Australia.

But the backlash against her work for Procter & Gamble highlights the challenge of addressing masculine stereotypes. A core criticism is that it lacks the positivity of femvertising, such as the 2014 #LikeAGirl campaign for Procter & Gamble’s brand Always, which turned a phrase used to insult boys into an empowering message.

The LikeAGirl campaign.

Other brands marketed to male customers have managed to avoid criticism while dumping the toxic stereotypes they have previously peddled.

Unilever’s brand Lynx (also known as Axe) is a good example. It had a history of using sexual objectification in its advertising for men’s personal grooming products. In 2011 the British Advertising Standards Authority banned six of its adverts for being demeaning and offensive.

In 2016 it reformed its image with the #FindYourMagic campaign, which challenged narrow notions of masculinity.

Real men can love kittens: Lynx’s #FindYourMagic campaign challenged masculine stereotypes. Supplied

It followed up in 2017 with its #IsItokforGuys campaign that aired the private struggles men experience with the pressure to “be a man”.

The Australian soft-drink brand Solo, owned by Schweppes, is another example of marketers dropping their reliance on aggressively hyper-masculine stereotypes without backlash. In its recent A Thirsty Worthy Effort campaign, a man is no longer engaging in extreme sports to get an extreme thirst; he’s making a costume for his daughter’s school play.

Uncomfortable dialogue

Lynx celebrated men being themselves and unpacked unhealthy and narrow expressions of masculinity. Solo used humour to celebrate men taking an active role in domestic life. Where Gillette has dared to be different is in how the advertisement speaks to its male audience.

It directly and unflinchingly tells men how they should behave: do not bully, patronise, speak over, humiliate or sexually harass women. It tells men how they should treat one another. It challenges men to hold one another to account and set better role models for the “men of tomorrow”, cautioning that “the actions of the few can taint the reputation of the many”.

It shows the huge creative challenge the #metoo revolution poses to advertisers. How can you celebrate masculinity without addressing the toxic behaviours exposed by #metoo revelations?

Gillette’s commercial appropriation of #metoo may sit uncomfortably with some, but advertising is often at its most powerful when it captures the zeitgeist.

Encouraging men to call out how others behave around, speak about and treat women is critical in affecting change and advancing gender equality. Gillette’s statement reinforces this: “If we get people to pause, reflect and to challenge themselves and others to ensure that their actions reflect who they really are, then this campaign will be a success”.

Its approach to challenging male stereotypes and expectations has raised an uncomfortable and provoking dialogue. Representing men as vulnerable, kind, empathetic and modest in advertising is imperative if we are to move beyond the limited cultural portrayals that we often see of men. It is a step forward for an industry with a very chequered past.

Lauren Gurrieri, Senior Lecturer in Marketing, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.