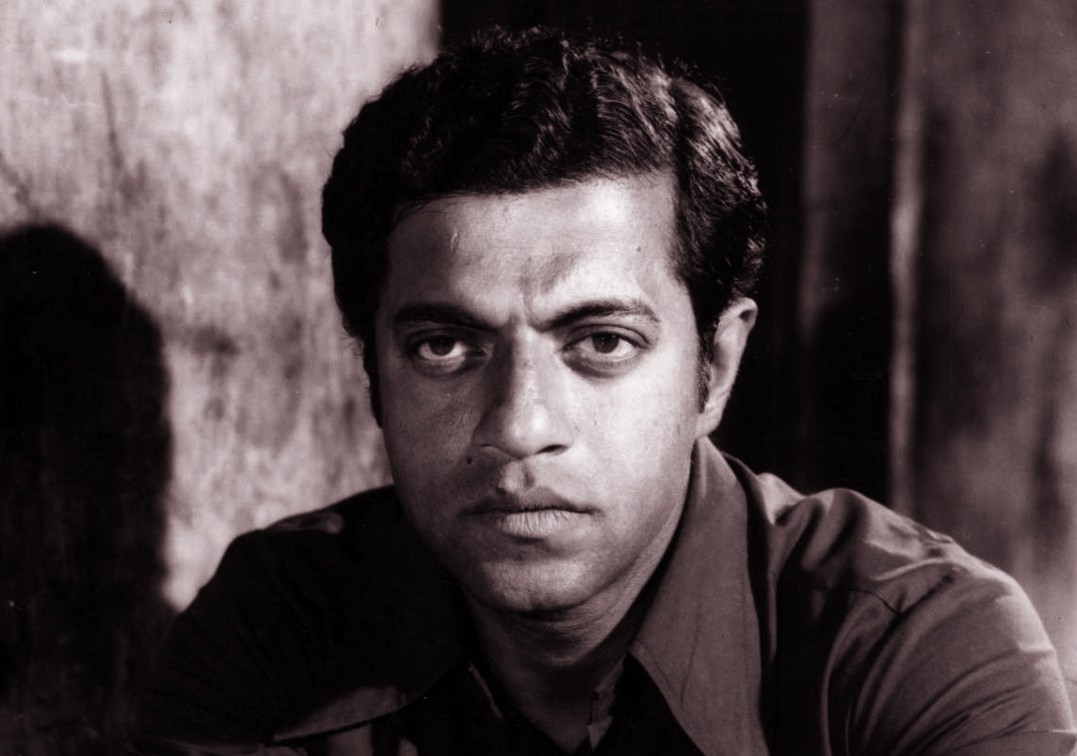

Girish Karnad acted in several plays and movies that have received critical acclamation. Karnad, a recipient of Jnanpith Award, was also conferred the Padma Shri in 1974 and the Padma Bhushan in 1992.

Bengaluru: “Eternal vigilance is the price of freedom. I would say that people like me who have been honoured by the state should use it for a purpose. This is the way I return my debt to the country” – Girish Karnad in Indian Express.

Was there ever someone not offended by what Girish Karnad had to say? His brand of theatre offended a certain section of society, his activism others.

In September, Girish Karnad sat with carried a placard that read ‘Me Too Urban Naxal at an event organised to mark the first death anniversary of journalist-activist Gauri Lankesh in Bengaluru. There were tubes under his nose and he was battling ill health but turned up nonetheless.

Speaking to the gathering on the first death anniversary of Gauri Lankesh, Girish Karnad had spoken up against the house arrests of activists across the country.

Girish Karnad was later charged for wearing the placard around his neck at the event.

“A year ago, he had turned up at Town Hall in Bengaluru to take part in a protest following Lankesh’s assassination. In 2015, Lankesh had been with him at the same spot — in a protest against the murder of scholar MM Kalburgi. As it now turns out, an invisible net had been tightening around these three public figures from Karnataka. Investigations by an SIT of the Karnataka police has uncovered a far-right, militant Hindutva conspiracy to kill Lankesh and Kalburgi — and a hitlist of targets. The first name on the list was Girish Karnad,” Indian Express reported.

A fearless social and political activist, Girish Karnad, was also one of the 200 writers who issued an appeal to Indians in April to vote out hate politics in the Lok Sabha elections and vote for a “diverse and equal India.”

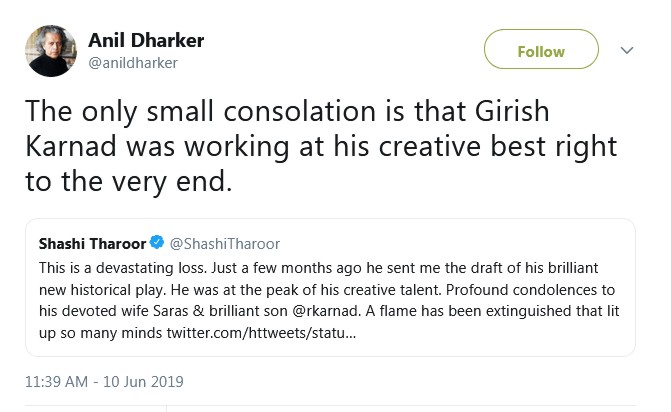

Till his last breath on June 10, he was active both in his activism and playwriting. He was ready to debut his newest historical play.

Karnad succumbed to a prolonged illness at his residence in Vittal Mallya Road, Bengaluru, on Monday.

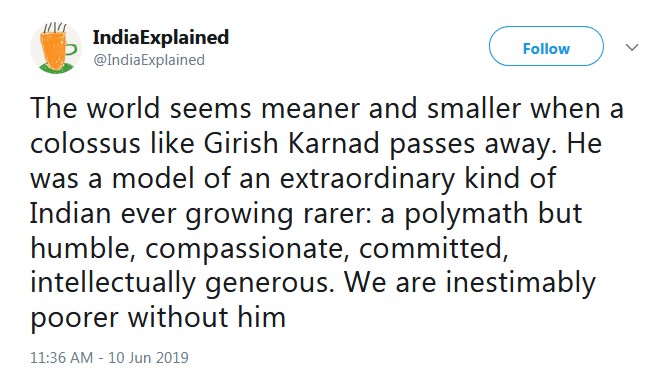

He is often credited alongside other theatre stalwarts of his time with shaping the modern Indian theatre we see today.

Girish Karnad acted in several plays and movies that have received critical acclamation. Karnad, a recipient of Jnanpith Award, was also conferred the Padma Shri in 1974 and the Padma Bhushan in 1992.

He was also a Rhodes Scholar from Oxford University, in the 1960s that earned him his Master of Arts degree in philosophy, political science and economics.

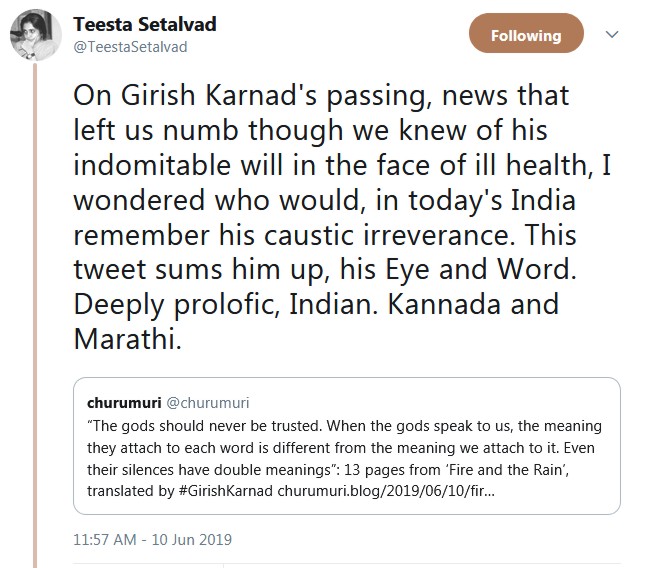

His plays, written in Kannada, have been translated into English and several Indian languages. Karnad was one of the most prominent artistic voices of his generation.

He was an eminent playwright with works such as “Nagmandala”, “Yayati” and “Tughlaq”, which was one of the most successfully performed plays, to his credit.

He also worked in Hindi cinema’s parallel film movement in movies such as “Swami”, and “Nishant”. His TV credits include “Malgudi Days” in which he played Swami’s father and a hosting stint in the science magazine “Turning Point” on Doordarshan in the early 1990s.

“With drama as his chosen literary form and Kannada as his principal language of original composition, Karnad certainly exemplifies the transformative practices of his generation, but he has also carved out a distinctive niche for himself with respect to subject matter, dramatic style, and authorial identity. The majority of his plays employ the narratives of myth, history, and folklore to evoke an ancient or premodern world that resonates in contemporary contexts because of his uncanny ability to remake the past in the image of the present. Karnad’s engagement with myth (especially certain episodes in the Mahabharata) begins with Yayati in 1961, continues in Hittina Hunja (The Dough Rooster, 1980; rewritten in English as Bali: The Sacrifice, 2002), and culminates in Agni Mattu Malé (The Fire and the Rain) in 1994. The line of history plays moves from Tughlaq (1964) to Talé-Danda (Death by Decapitation, 1990) and The Dreams of Tipu Sultan (1997). Folktales from different periods and sources provide the basis of Hayavadana (Horse-Head, 1971), N”aga-Mandala (Play with a Cobra, 1988), and Flowers: A Monologue (2004). Anjumallige (literally, ‘Frightened Jasmine,’ 1977) is the only early play by Karnad with a contemporary setting — Britain during the early 1960s — and his most recent work, Broken Images (2004) is the only one to be set in present-day India. During the 1961-77 period, therefore, each successive play by Karnad marks a departure in a major new direction and the invention of a new form appropriate to his content — ancient myth in Yayati, 14th-century north Indian history in Tughlaq, a 12th-century folktale interlineated with Thomas Mann’s retelling of it in Hayavadana, and early-postcolonial Britain in Anjumallige. In the later plays, this quadrangulated pattern repeats itself in a different order, creating a cycle of myth-folklore-history in Hittina Hunja, N”aga-Mandala, and Talé-Danda (1980–90), and a second cycle of myth-history-myth- contemporary lifefolklore in Agni Mattu Malé, Tipu Sultan, Bali, Broken Images, and Flowers (1994–2004),” wrote Aparna Bhargava Dharwadker, a professor of English and Interdisciplinary Theatre Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison in Firstpost.

To say that Girish Karnad was ahead of his times is an understatement. He had a hold on theatre, literature, cinema and science.

Nagamandala dealt with intimate relationships between a man and a woman, and an Indian woman’s desperation to win the affections of her husband in spite of the husband’s open infidelity. It also touches on the imposition to prove fidelity on married women while their husbands are not questioned about their extramarital affairs, and the village judicial system.

The play Hayavadana is based on the idea that humans are imperfect and thus have a number of limitations. The play also deals with woman emancipation. Padmini gives preference to her sexual desires and gets an opportunity to remain with both the persons she loves though fails to fulfil her desire (mind of her husband and body of her lover).

“Krishnabai Karnad remained a big influence on her third son’s life, allowing him to conceive of women’s desires in plays like Hayavadana (1971) and Nagamandala (1988). The house in Dharwad was also full of girls his age — two sisters and four cousins. “You know what a first cousin means in south India? She could be a sister or a wife. You are with her at a time when you have become sexually aware, and you know the ambiguity of the relationship. In most communities in north Karnataka, after the age of eight or nine, girls and boys hardly communicate. In our community, there is much more openness. We used to sit together and talk, about who we felt attracted to, or how Raj Kapoor was very handsome,” he recalled in the IE report.

Girish Karnad starred in the Telugu film Ananda Bhairavi (1983) where he played a dance teacher who protests when girls are barred from performing Kuchipudi.

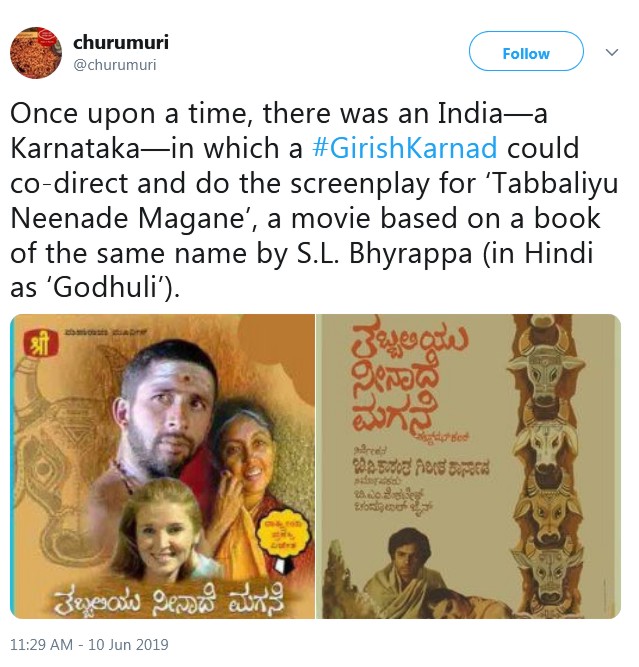

Karnad had made his acting as well as screenwriting debut with a 1970 Kannada movie Samskara. The film, based on a novel by UR Ananthamurthy and directed by Pattabhirama Reddy, won the first President’s Golden Lotus Award for Kannada cinema.

Archana Nathan had written in Sabrang India that ‘Girish Karnad in ‘Samskara’ Takes on theBrutality of Caste.’ As much as he loved Samskara in 1970, Karnad shared an uneasy relationship with Ananthamurthy’s other novels, even going to the extent of openly dismissing the late writer’s legacy. On the same occasion, Karnad even called Samskara “baseless” and “shallow”.

“Karnad wrote Tughlaq (1964) when he was 26 years old, creating a metaphor for authoritarianism that becomes relevant with each new bend in modern Indian history. When it was first published, the play’s depiction of Muhammad bin Tughlaq’s idealism, his efforts at creating a more secular state, his far-sighted ideas about the economy and his eventual disintegration into a mad tyrant seemed to provide a striking parallel to the disenchantment with Nehruvian ideals that had swiftly set in after Independence. During the Emergency, Tughlaq’s ruthlessness became a way to understand the way democracy could be gamed by a popular leader. “History is interesting because it gives me the essence of today’s living,” the playwright told the Indian Express.

“Karnad isn’t looking history in the eye alone. After six decades of life as a playwright, cinema actor, television actor, filmmaker and often irascible public intellectual, he continues to pitch himself into the battles of the present. On September 5, at an event to mark the first anniversary of journalist Gauri Lankesh’s assassination and a couple of days after the arrests of lawyers and activists by Pune police, the actor-playwright turned up with a placard hung around his neck: #MeTooUrban Naxal. “[The fantastic allegations] shows that the police… are implicitly saying that we can say what we like, which means we can do what we like,” he said to a packed audience,” the report said.

“He is disheartened by the religious hatred that seems to course through India in 2018. “It has been transformed into this utterly futile and dangerous game in this dream of becoming a Hindu rashtra. We already had Pakistan and this way we are creating another one. It is dangerous because Hindutvawadis never tell you how this Hindu rashtra will accommodate untouchables, tribals, women,” the report added.

He never shied away from taking on the high and mighty. At a press conference in New Delhi in August 1994, noted playwright Girish Karnad issued a statement after the Babri Masjid demolition and the Hubli ‘Hungama’. As the sangh parivar’s propaganda machinery relies heavily on public memory being short, Sabrang India reproduced the statement in its entirety in 2004 to put the campaign of the Sangh parivar on the Hubli controversy in its proper perspective.

“For decades now, Karnad has been an unequivocal voice against majoritarianism and excesses of the state. It is a voice that carries far — and as the backlash against his defence of “urban Naxals” show, including a police complaint against him — these days it has consequences. Ramanathan remembers that when activists of the Ambedkarite-Marxist cultural group, Kabir Kala Manch, were arrested in 2012 under the UAPA, few intellectuals in Maharashtra were ready to stand up and speak for them. “Karnad flew in from Guwahati. He was extremely well prepared and had studied the legal documents. He spoke lucidly about civil liberty and what was at stake,” playwright Ramu Ramanathan said in the Indian Express report.

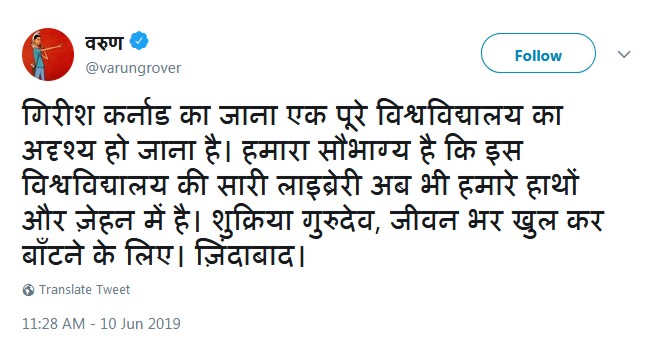

The cultural world is inevitably poorer without its foremost warrior.