Results for the recently held Uttarakhand assembly elections will be released tomorrow, yet no matter which political party comes to power, it has its hands full.

Women farmers in Jukanoli village, in the hill district of Almora, Uttarakhand. The state’s hill districts are still struggling with low per capita income, bad access, poor healthcare facilities, unemployment, decline in agricultural output and neglect.

Uttarakhand, the Himalayan state which borders along China, is the sixth richest state in India in terms of per capita income but those living in its hill districts benefit less from this development than those in the plains.

Consider this: The per capita income of Haridwar, a district in the plains that is 53 km from state capital Dehradun, is Rs 122,172. But Uttarkashi, the northern-most Himalayan district, reports half that per capita income at Rs 59,791, according to the 2014-15 Statistical Diary, Uttarakhand. This is close to the per capita income of Jharkhand which ranks among the 17th in the country.

The irony is that Uttarakhand was carved out of Uttar Pradesh (UP) in 2000 precisely so that exclusive attention could be given to the development of its remote hill districts. These had been left neglected by successive governments based in UP’s capital Lucknow, around 600 km from Dehradun.

Sixteen years since, the mountain districts of Uttarakhand are still short of basic facilities, especially healthcare. There are no jobs to be had in these districts and this is leading to large-scale migration to the plains, leaving entire mountain villages uninhabited. And farming, which used to be the principal occupation in the hills, is crippled by small land holdings and a lack of government agri initiatives that neighbouring Himachal Pradesh sees in plenty.

“Uttarakhand was not founded for the development of Haridwar and Haldwani (cities in the plains) but for the development of the 16,000 plus villages in the hills of the state. But nothing is being done for them,” said Anil Joshi, environmental activist and convenor of the Gaon Bachao Andolan (save the village movement), a campaign to tackle the state’s migration issue.

At Rs 122,804 Dehradun’s own per capita income is closer to that of Haridwar. Though it is a hill district, it benefitted from being the state capital.

Rich state, poor health: Only 68% health centres function well

Uttarakhand’s health infrastructure is facing a crisis, as IndiaSpend reported in February 2017–only 68% of its primary health centres that form the frontline of the public healthcare system work 24×7, as they are supposed to. The second-rung community health centres are short-staffed–they are 83% short of emergency specialists and have half the number of nurses needed.

Uttarakhand also suffers poor infant mortality rates (IMR), ranking 18th among 29 states, according to an Observer Research Foundation analysis. But the hill districts of Rudraprayag, Pithoragarh and Almora record fewer infant deaths despite their inaccessible terrain. It is the well-developed pilgrim district of Haridwar that reports the worst figure of 70 deaths per 1,000 infants (2012-13), the same as conflict-ridden Congo. Haridwar also represents a high rate of stunting–low weight for height–52% in children under five, compared to Pithorgarh’s 22%.

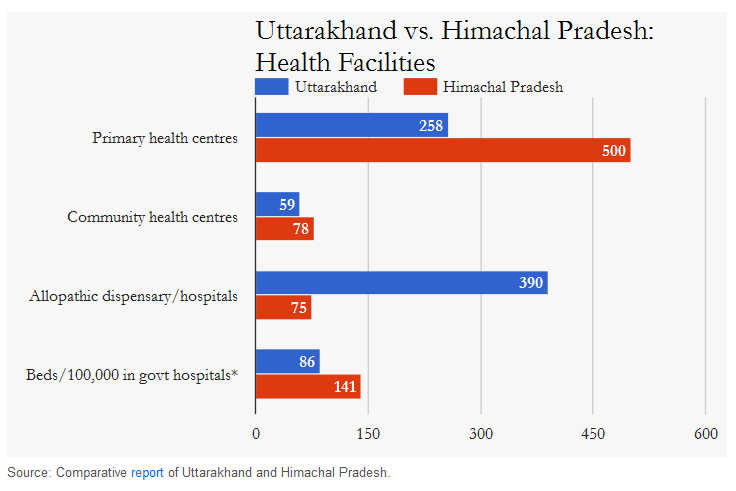

Himachal Pradesh too has a problem accessing hilly districts but it is doing much better than Uttarakhand on the healthcare front as this comparative report of the two states for 2014-15 shows. Himachal Pradesh has 141 beds per 100,000 people compared to 86 beds in Uttarakhand–which has 47% more population (10 million) than the former (6.8 million). Himachal Pradesh has nearly double the primary health centres (500) Uttarakhand does (258). And its community health centres (78) outnumber those in Uttarakhand (59).

Ghost villages in the hills: 1,048 emptied out completely

People living in the mountains have always migrated to cities in the plains in search of white-collar jobs. But they would leave their families, or a part of it, behind. Now migrations to the plains involve entire families moving from the hills to the plains, either within Uttarakhand or to other parts of the country, said locals.

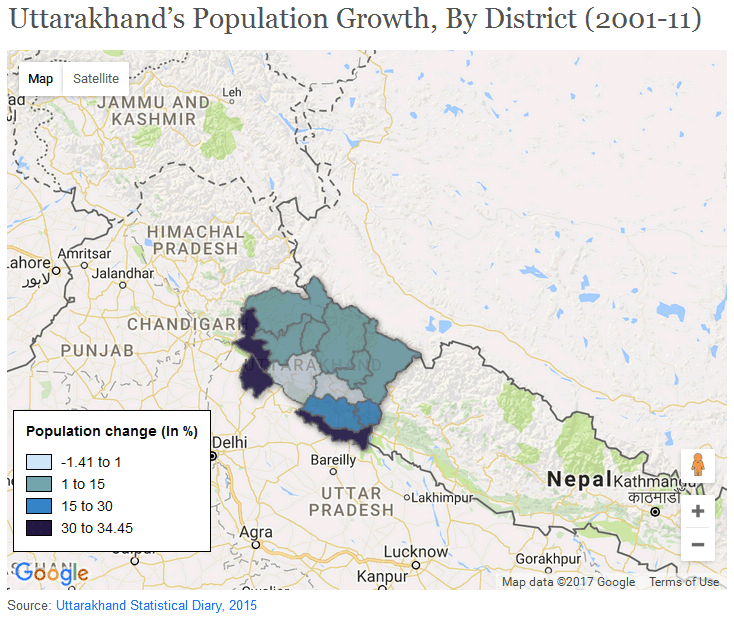

While hill districts saw a decadal population growth of 12.75%, the plains recorded almost 32%. This is a sure sign of large scale migration of entire families from the hills.

There are 1,048 villages in the state that are uninhabited—“ghost villages”, according to Census 2011. Here migration has emptied out entire villages.

There has been a negative decadal growth observed in the districts of Almora (-1.28%) and Pauri Garhwal (-1.41%). The population in both districts together fell by 17,868 persons between 2001 and 2011.

In 2015, the National Institute for Rural Development and Panchayat Raj conducted a survey of 217 households in Almora and Pauri Garhwal to understand the dynamics of migration and its impact on the village economy. They found the following: 88% of households reported having at least one person migrating for a job; 86% of those who had migrated were men, 51% of them were between 30-49 years. Also, 73% of them reported migrating for durations between six and 12 months.

The top reason for migration was employment–47% of migrants cited the lack of job opportunities in their home districts. And 18% said they migrated anticipating better jobs in cities while 17% said they had landed jobs or were being transferred out by their existing employers.

“The attraction to cities arising due to hardships of village life in hills such as poor transport connectivity, lack of water, inadequate medical facilities, poor educational facilities and inaccessible markets have (sic) further accelerated the process of migration of youth,” said the paper.

Uttarakhand’s literacy rate at 78.8% is higher than the national average of 73%. The teacher to student ratio in primary section is 1:23 compared to the national figure of 1:41.

“With the kind of education that we are offering our children, there are no jobs for them here in Uttarakhand,” said Shekhar Pathak, former professor at the Kumaun University and founder of the People’s Association for Himalaya Area Research (PAHAR). “We are unable to offer youngsters dignified jobs in the state and hence entire families have been migrating.”

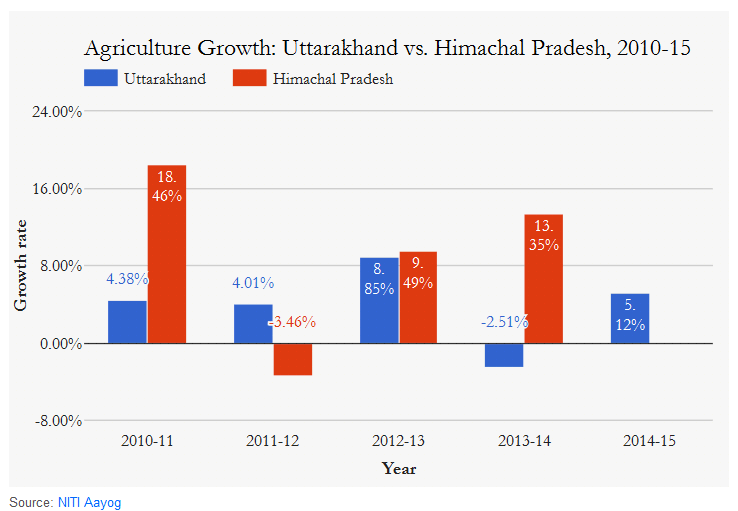

Falling yield: Agriculture growth slows to 4%

There has been slowing down of growth in agriculture and allied activities in Uttarakhand. Its annual, average growth stood at 4% between 2010 and 2015 compared to Himachal Pradesh’s 9% in the same period.

“Himachal Pradesh earns more than Rs 15,000 crore every year from horticulture and agriculture because of its government policies. The Uttarakhand government never focussed on developing agriculture and that is why there is this deep decline,” said Joshi.

Also, smaller land holdings give smaller returns on investment and 73% of all farmers in the state are marginal, with less than 1 hectare of land according to the state statistical diary.

With migrants abandoning their land to the elements, vacated farmlands are attracting wild animals from surrounding forests and this is leading to animal-human conflicts. Even though a notification passed in February 2016 allows the culling of wild boars, the implementation of the notification has been poor.

“Villagers say that even if they work in the fields, their crops will be destroyed by monkeys and boars, so what’s the point?,” said a senior officer working in the horticulture department requesting anonymity. He also pointed out that climate change has pushed fruit cultivation to even higher altitudes, causing a drop in the production.

“An upwards altitudinal shift in cropping has been reported in cash crops like apple, rajma, potato and carrot. Some projections speculate on an increase of night time temperature (Dimri and Dash, 2011) which may not only lead to decrease in production of some crops such as rice, but also reduce the winter killing of pests, hereby decreasing crop yields,” said 2015: Climate Change in Uttarakhand, a report by the Centre for Ecology, Development and Research.

There has also a drop in annual rainfall in the region that has impacted the state’s dominantly rain-dependent farming. “Most of the old water sources are drying up, agriculture is becoming very challenging,” said the official.

An analysis of temperature and rainfall data over 100 years shows a decline in rainfall that grew steeper after 1970s. “Although the average reduction rate in annual total rainfall has been insignificant, yet it may put great stress on the water resources of the region. The rainfall declining trend (sic) is not the same all over the state,” noted Changing Climate of Uttarakhand, a paper published in 2014 in the journal Geology and Geosciences.

Haridwar received more rainfall than normal while all other districts witnessed less precipitation. “This rainfall shortage is more acute in Pithoragarh, Bageshwar, Almora, Champawat and Nainital Districts,” the report further noted.

Older residents said that tougher conditions for agriculture mean that it is harder for the youth to resist the pull of migration.

“Youngsters here prefer to work as security guards in Delhi earning a measly Rs 3,000 a month than working here. They see no future here,” said the senior officer in the horticulture department.

(Yadavar is principal correspondent with IndiaSpend.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.

This article was first published on IndiaSpend