The temple in Sankad village with two different fire pits for the Scheduled Castes (left) and the upper castes.

Dhanera, Gujarat: A temple with two entrances opens up to a broad hallway that leads up to two fire pits in front of two doors marking separate entries to different temples. One temple remains open while the other is closed—members of the local Scheduled Caste (SC) Gohil community identify the closed one as theirs.

As this reporter goes towards the closed side of the temple, the priest enters from the other side. “It’s an age-old custom. The temple is 100 years old; some things cannot be changed,” he answers when questioned about caste discrimination.

Untraceable custom

The 68-year-old priest continues to support the discriminatory custom. “We do not do any injustice but temples should be different,” he says adding that “there were differences, as taught to them, that is part of the culture”.

The temple is located in Dhanera Taluka’s Sankad village, in the Banaskantha district of Gujarat. Newlywed couples come to seek blessings at the temple, which is shared by 30 villages.

“Is God different? Are our offerings different? Is the cause of the visit (marriage) different? Then why can’t we share the same space?” questions Sankad native Dinesh (35).

Temples in the villages of Saral, Thawar and others in Banaskantha also have similar tales of discrimination to narrate.

A teenager from an SC community peeks into the temple in Sankad.

When women from the Gohil and Solanki communities went to attend a Navratri function in Saral, they were asked to leave. “We were not allowed to dance, sing or participate in the puja and asked to leave,” says Meeta, who firmly believes in the principles of BR Ambedkar.

Women of Saral village believe only in the principles of BR Ambedkar.

At the Shiva temple in the same village, women from these two communities who fast for 16 Mondays during the holy month of Shravan are barred. “We are asked to stay away and maintain the difference,” says Meeta.

Even dead bodies of members of SC communities are discriminated against because of their castes. In all the 94 villages of Dhanera Vidhan Sabha, there are different crematoriums for different castes.

The discrimination does not end here. There are pending court cases over ownership of crematorium land in Vasan and Malotra villages. The SC community of Vasan alleges that the land, allocated by the collector to it for 40 years, was hijacked by the sarpanch and other upper-castes. A similar incident allegedly happened in Malotra, where the land is demarcated by a fence.

Ostracisation from public spaces to settlements

An unmetalled road along an open crematorium leads to a settlement in the woods in Sankad. The settlement, which bears all the marks of ostracisation due to its far-off location, has mud houses with hay boundary walls. They belong to the Valmikis, the last in the caste system, who are oppressed even by the SCs of the village.

Caste discrimination in these villages does not start with the Brahmins. The Other Backward Classes oppress the SCs (Gohils and Solanki), who, in turn, discriminate against the Valmikis.

Geeta, making millet chapatis for lunch at one of the houses, is the youngest and the most educated among the three sisters-in-law in the family. She had studied up till the 8th grade. “We are not allowed to raise our voices. If we do, we are abused,” says the 19-year-old, who could study only till class eight.

In 2017 and before, the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) Assembly election manifestos consistently promised to eradicate caste discrimination in Gujarat. However, these villages tell a different tale.

“During the last campaign, candidates promised to construct metalled roads and permanent houses. But you can see the condition of the road you took to reach our house,” Geeta says sarcastically when asked about the election campaigns of political parties adding that “they visit us once in five years only to ask for votes”.

From weddings to other public events, the Valmikis use their utensils and sometimes even carry their own food to marriages. For the comparatively less underprivileged SC communities of Solankis and Galchars, the situation is slightly better due to their vote bank. “They have separate utensils for us in their houses,” says Dinesh, a member of the Gohil community in Sankad.

The temple used by the Valmiki community.

“The difference is evident. Our newlywed couples cannot enter temples and are supposed to worship from outside. We carry our utensils and sometimes food too to their weddings. They mostly don’t attend our weddings—and even if they do, they give cash and leave,” Shilpa, another member of the Valmiki community says describing the deep-rooted discrimination.

Even election candidates visiting the Valmiki settlement “do not enter the houses or touch the community members. They give verbal assurances and leave”, adds Shilpa. Some of the candidates enter the houses of other less underprivileged communities and have tea during campaigns.

Shilpa’s husband Bhangi Pagwan Bhai Virchand tried several times to apply for the position of Safai Kamgaar. Finally, he gave up and expected their son Shivam, who has a master’s degree, to improve the family’s financial condition. But he too failed to land a job and now assists his father and uncles in farming.

Shilpa’s husband Bhangi Pagwan Bhai Virchand shows the forms which he filled to get a house under the PM Awaas Yojana.

Caste discrimination stretches to government schemes as well. Shilpa’s family applied for a house under the PM Awas Yojana thrice but their forms either failed to reach the concerned officials or were ignored. “Once an officer from Palanpur even visited our house for inquiry. He said that since we already have a roof, we do not need a house,” says Shilpa, who stays with the six family members in a one-room house with no washroom or a permanent roof.

Oppression: From land to representation

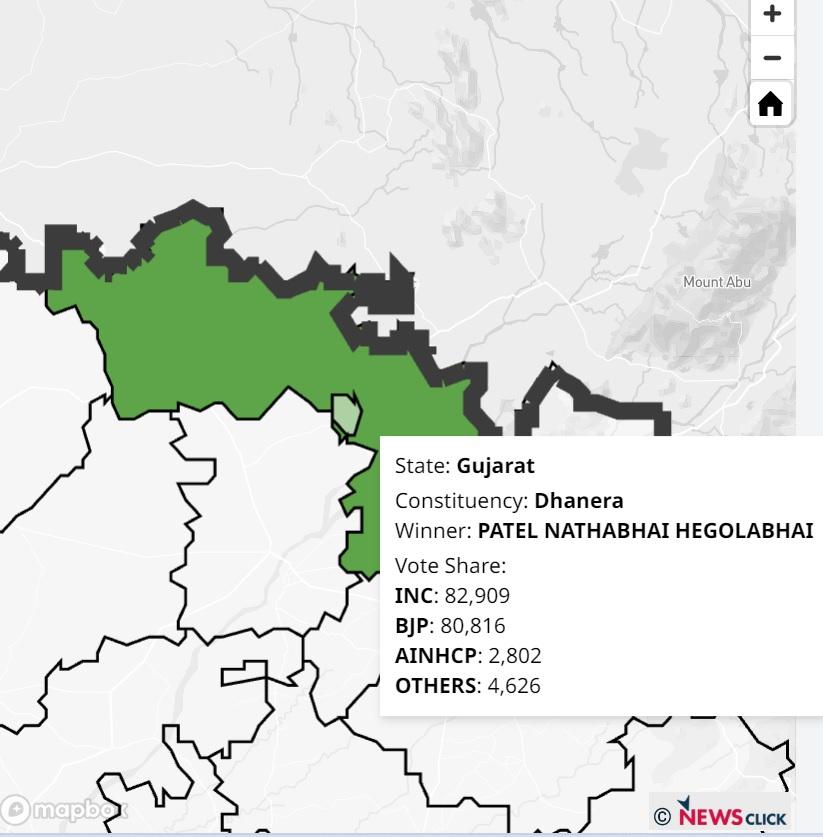

Dhanera is one of the biggest constituencies containing SCs, who total 28,000. Besides, it has a tribal population of approximately 9%. But neither SCs or Scheduled Tribes (STs) have any representatives.

“No one from the SC or ST community can contest even in Panchayat elections without a reserved seat. An analysis of the unreserved seats in Panchayat election shows a clear picture of the situation here,” says Pankaj, a local reporter and son of a former sarpanch.

Gujarat was among the top five BJP-ruled states with the highest number of crimes against Dalits in 2018, according to the National Crime Records Bureau.

As per the rules, the underprivileged have been granted some government land for farming. Masra Hamira Galchar (62), a native of Malotra, lost his land in 2019 and son in the first wave of the pandemic. He now works as a daily wager in the lands of other farmers for Rs 200 a day.

In 2002, Galchar was granted six bighas. When the water crisis hit the village, he could not afford to spend lakhs on a borewell. With no option left, he approached the village Patel, who arranged for irrigation on the condition that he would have a “75% share in the produce”.

“I was left with only one-fourth share despite slogging on my land,” adds Galchar. In 2018, he finally asked the Patel for another share. When he refused, Galchar stopped working for him.

Galchar collected his crops in one place to sell some of them and use the rest for as cattle feed. The same night, the “Patel and a few other men burnt his crops”. When Galchar and his family rushed to extinguish the fire, they were “beaten up”.

When he registered an FIR at the Dhanera Police Station, the Patel claimed that the land belonged to him and Galchar had instead burnt “his” crops. The police believe his version and the case has been pending in a Palanpur court for the last four years. Since the matter is sub judice, Galchar can’t use the land.

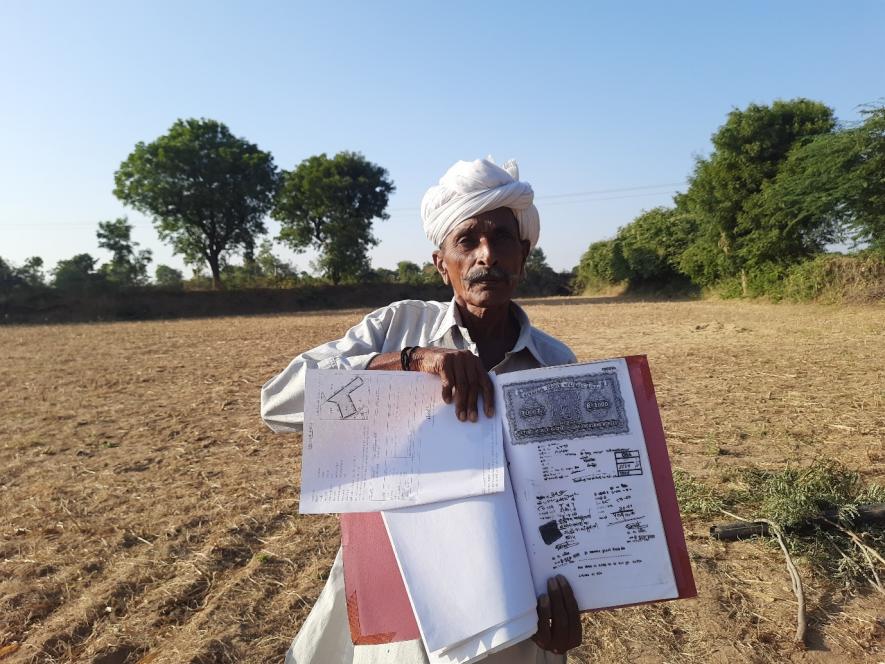

Masra Hamira Galchar, of Malotra village, shows his land papers.

“Being of the same caste matters more than being fair,” Galchar says with fading hope and a hunger for justice in his eyes while showing documents and a copy of the FIR in support of his claim to the land.

Galchar, who has a debt running in lakhs, has already spent, at least, Rs 3 lakh on the court case. When asked about how will he pay the loans or whether he is sure about getting his land back, he replied with only a pitiful smile.

Meanwhile, the Patel has his own house and lands, and continues his ‘one-fourth share’ business with other farmers of the village.

Caste-based atrocities against Dalits and tribals in Gujarat spiked by, at least 70%, between 2003 and 2018. Despite the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh’s (RSS) pledge to eliminate caste discrimination, the situation hasn’t changed.

“It is this way to keep honour intact,” asks Shilpa pointing out

the separate entries to the Sankad temple.

Saral is also known as Ambedkar Nagar. However, fasting Dalit women are not allowed inside temples. Caste discrimination in villages of north Gujarat is part of the culture and the social fabric.

The writer is a Delhi-based freelance journalist reporting on issues of unemployment, education and human rights.

Courtesy: Newsclick