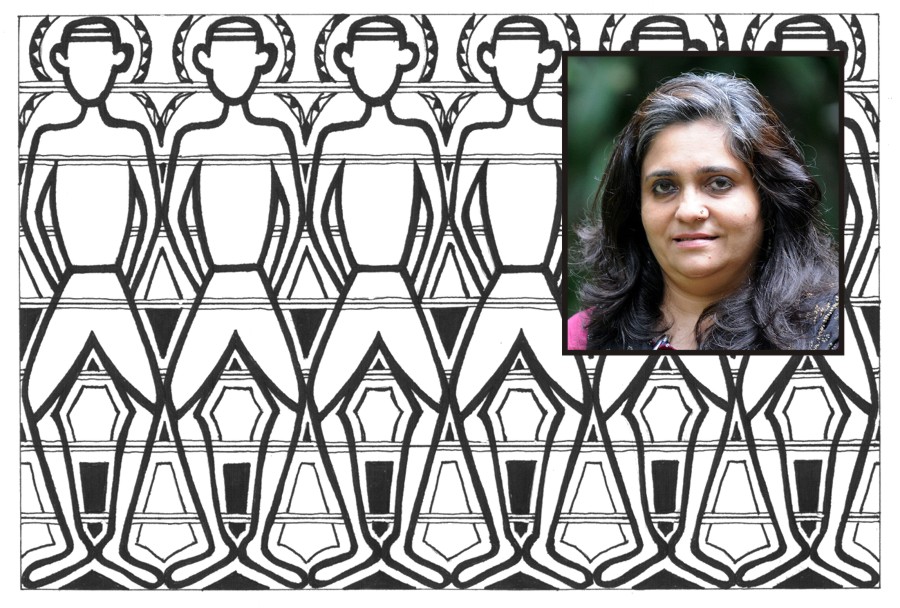

As journalist and human rights defender Teesta Setalvad spends another night in Gujarat’s Sabarmati jail, Sabrang India looks back at some of her most powerful work (and words) over the last thirty years – work and words deemed dangerous enough to be imprisoned. This is the struggle of our memory against forgetting, against the white-washing and clean-chitting of violence.

A half-baked secularism

Despite the brutal loss of half a million lives when this country was partitioned on religious lines in 1047, the national leadership, after close and passionate debate decided that India would remain secular and a democracy. It was a principled decision, large enough to swell our pride, but along with that it was an intensely pragmatic one. If India emerged poor but powerful, handicapped yet large in its vision, it was thanks to this decision, pragmatic and principles. For no other way could such a vast and diverse people, diverse in language, ritual, tradition, culture and religion stay together but for this vision of oneness, a oneness moreover assured by equality. This vision of a oneness could not have been possible without the contribution of Untouchables to the pre-Partition debate, a contribution that drew from their own denials and segregation, a contribution that could see clearly that, from their understanding of Indian society, if genuine democracy, and secularism had to be attained, equality in citizenship and before the law was as vital as freedom of expression and freedom of faith which has implicit within it the freedom from faith, too. This depth of understanding is absent today.

This oneness envisaged and assured in the Indian Constitution authored by Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar, is today deeply threatened. Despite being involved intensely in the struggle against the manipulation of religion in the pursuit of power, I cannot be sure that we will win. Eminent columnist, Khushwant Singh’s passionate book, The End of India, sees dark days ahead, India splintering into a thousand pieces thanks to bitter pogroms against the minorities led by the leaders of Hindu majoritarianism.

Historically, from the medieval ages right down to the modern, religion when it influences the state, and politics, have proved destructive and poisonous. For Christianity in the medieval ages, the inquisitions remain actions yet to be faced and lived down. Hundreds of thousands of women burnt at the stake as witches during the dark ages, alerts us to the fact that when the potent mix of religion and state takes place, the patriarchy of both turns first on women and their sexuality. The irreligious Jinnah tolerating poisonous speeches in the name of faith at Aligarh and other parts of UP that finally led to the bloody vivisection of the subcontinent may or may not be something that many wish to remember. But his cynicism and the League’s politics had a hand in altering, drastically, the politics of this subcontinent and also lived perceptions in the minds of ordinary Indians. Today the brand of political Islam prevalent in a majority of Islamic countries battling modernity and failed to divorce faith from the state is manifest as a pathetic absence of democracy. The figure of Bhindranwale, was propped up, through the violence and hatred that he generated by former Indian leaders themselves and we had to pay for it. For Indians committed to Indian pluralism and diversity, the plight of Buddhism, a religion born here but not allowed to survive has been a matter of deep perplexity, even shame. But hop across to Sri Lanka and you can see Buddhism influenced with all the negatives when religion and state intermingle. There is a blatant privileging of the majority faith and language too –Sinhala Buddhists. And, not to be left behind, the brutal growth of forces that are manipulating the Hindu faith to gain state power in India and then transform Indian democracy to a fascist state, have used brutal genocide and violence to achieve their space and place. It was Advani’s bloody rath yatra that brought the BJP to power in the centre and Modi-like genocides that may keep it there if Indian resistance does not match this onslaught. Religion in the public sphere retains little of original faith – be it Christianity, Islam Sikhism Buddhism, Islam or Hinduism.

Are we witnessing in our life times, the end of India? Our first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, astutely identified Hindu communalism as the greatest threat to Indian democracy. “If fascism were ever to come to India it would come in the garb of Hindu rashtra,” he both said and wrote. But as we battle on to assert secular principles in an India threatening to go under, the limitations of even this analysis or vision imbibed by the entire secular and left constituency stares us in the face.

Secularism is the separation of religion from state and equal respect for all religions within society. Granted. To this narrow and limited extent, the battle for secularism is clearly articulated. Where we have singularly failed is understanding what faith in India and for the Hindu faith means. But this is, at best a half-baked notion of secularism in the Indian content. Put pithily, can you battle against the separation of religion from state in the Indian context without battling caste?

Here the deep-seated caste bias among left intellectuals and secularists hits us sharply in the face. We have responded ably with this half-baked secularism when assaults on religious minorities have taken place but remained paralysed and shamefully silent when caste violence erupts, Dalit women are paraded naked and violence in the name of caste is unleashed.

This paralysis and silence reveals a shallow understanding of religion within the Indian context. In India, we simply cannot speak of organised Hindu religion without dealing with, or battling caste. The individualistic and spiritual side of Hinduism, Islam, Christianity, Sikhism, Jainism or Buddhism may mean one kind of salvation from believer to believer, but each and every religion or faith has a political side, an organised side since men and women are both individual and spiritual and also political. This side of Hinduism is unassailably caste. In fact all faiths on the subcontinent have been influenced, or sullied by caste.

To speak, therefore of the separation of religion from state but not to link this separation with a concerted battle against the indiginities of caste and caste itself is not simply narrow and limiting it is constricting. In the sixth decade after Independence, the fact that such a narrow vision colours the battle for secularism also means that the vision is restricted by a deep bias.

Before Independence and after freedom was attained, deep schisms had emerged within the pioneers of the movement. Schisms that were consigned to dark recesses of historical evasion when a post-Independence Nehruvian vision blocked out the contribution of tribals and Dalits to this vision of a free India. The reason behind this relegation is abundantly clear. It s evident in what caused the schisms in the first place.

Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar as leader of the downtrodden, across the length and breath of the country, made his and his people’s presence felt in this battle for freedom. He struggled shoulder to shoulder and even, in some crucial areas went ahead. Be it him or Periyar, who split from the Indian National Congress because of Gandhiji’s withdrawal of the temple entry movement (the moment Brahmin clergy and their supporters among Indian bouguioise industry expressed deep discomfort of this move to radicalise from within), theirs was a deep questioning about who and what would be the beneficiaries of the freedom, hard fought and hard won.

Babasaheb said that 30 per cent of India at least, bedevilled by three thousand years of brutal denial was not simply interested in political freedoms if social and economic freedoms were not woven, intrinsically, into this concept. Though history has proved him tragically right, our post-Independence visionaries had no problems not simply relegating him to the shadows of history but even –shamefully—dubbing him a traitor.

Consolation must be had from the fact that if Gandhiji had lived he may not have allowed this sickening labelling. But his followers, Gandhians, as much as progressives and leftists, heirs of the Nehruvian vision and legacy did not hesitate in once more segregating a politics and thought that had emerged from within a historically oppressed section, to the dustbins of history.

The wonderful thing about genuine historical thought is that it emerges to haunt us, again and again. This is what is happening now. So far, the battles for a democratised history have been confined to the narrow confines of Hindu and Muslim rule. They have not entered into the realm of Dalit history, tribal history or even, really working class history or symbols. Feminist history too in this country has not been genuinely radicalised since it has so far been restricted to the stories of upper caste, middle class urban Indian women. That this is beginning to change is largely due to the assertions of quality minds and quality struggles from within the deprived, segregated sections.

This exclusion continued while on the other hand Hindutva or Hindu right wing began from the mid-eighties through the construction of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad and the Bajrang Dal, of a falsely-driven ‘all Hindu identity. Maliciously driven as the motivation was –because Dalits and Tribals are used for violence while caste discrimination is not eradicated and caste violence is condoned—it was born out of a recognition that Hindutva cannot succeed without manipulating and mobilising all castes, especially deprived sections. The appropriation of Ambedkar is part of this attempt. Mayawati’s open alliance with the BJP in UP is another. When she campaigned in Gujarat, there were 36 BSP MLAs contesting. Throughout her whirlwind tour she appealed for votes (from Dalits) for Modi. Not once did she ask that BSP candidates should emerge victorious.

It would be easy to dub this as cynical powermongering by a hungry and deprived lot. Which is exactly what a great number of secularists and progressives are doing. This lot finds it easier to sup with Mulayam Singh –no less ‘casteist’—than dine with Dalits. Why?

The heart is this historically practised exclusion by the elite of this country, especially the progressive, secular elite. They believe that secularism in India is limited to celebrating the Urdu ghazal or the composite culture epitomised in Akbar. The historical deprivations and denials, especially the hidden apartheid of caste as symbolised in untouchability, do not challenge their notions of democracy or secularism. The fact that caste is sanctioned and defined by Hindu religion and is therefore a part of organised Hindu religion itself is also conveniently avoided.

The battle for secularism in India simply cannot be won without addressing the issue of caste. It is about time that the battle for secularism in the Indian context breathes this in and imbibes it. Can therefore the battle to separate religion from politics in India be de-linked from the struggle to anhilate caste itself?