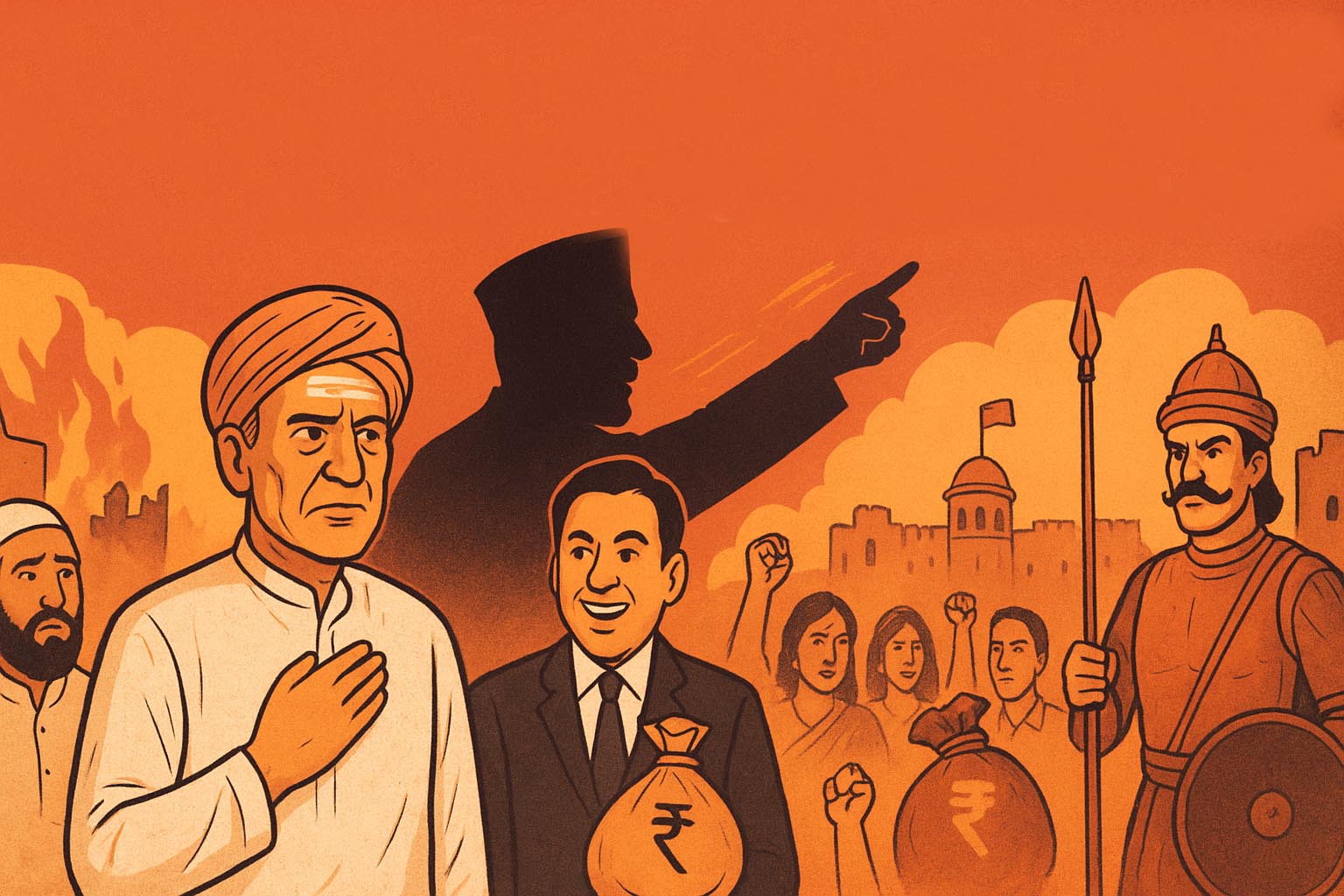

Much of the discourse on Hindutva politics in Rajasthan remains confined to historical debates—particularly Rajput–Muslim history. However, this obsessive engagement with the past often serves as a smokescreen for the real workings of Hindutva on the ground: exclusion and dominance within the administrative system, the scapegoating of select communities as narrative decoys, and crony capitalism that privileges traditional business elites.

Given that most anti-Hindutva critiques in the media emerge from the more privileged Brahmin–Bania perspectives, they inadvertently reinforce this diversion—keeping the focus on “Rajput history” and “Muslim history” while avoiding deeper discussions about present-day skewed representation, social engineering, and economic power in the state.

The real project is social engineering to secure Brahmin dominance in politics, bureaucracy, and culture. Crucially, this dispensation operates in tandem with Bania corporates, who reap massive economic benefits while Brahmins provide ideological legitimacy.

Cabinet and Leadership: It is numbers that matter

In early 2024, the BJP’s elevation of Bhajan Lal Sharma as Rajasthan’s Chief Minister, C.P. Joshi as state party chief and Babulal Sharma as Jaipur prantpracharak, signaled a clear shift towards Brahmin-Raj: three top Brahmin leaders at the helm, despite Brahmins being a small fraction of the state’s population. Although, after some uproar, C.P. Joshi was replaced by Madan Rathore (from OBC Teli) as the State president.

RSS Supremacy and Institutional Capture

The RSS, dominated by Maharashtrian Brahmin leadership, directs this design. Mohan Bhagwat, personally presided over major coordination meetings in Jodhpur held between September 5 and 7 this year, underlining Rajasthan’s importance in the evolution of a national Hindutva strategy. These gatherings link the BJP’s governance in the state directly to Sangh priorities: temple projects, Sanskritisation drives, and rewriting cultural narratives to affirm Brahmin custodianship of tradition. Rajputs, OBCs and SCs are recast as auxiliary players in a story authored by Brahmin ideologues.[1]

The increased focus on Maratha figures from the Peshwa period, despite their irrelevance or controversial relation with the state’s history. The state-level celebration of Ahilyabai Holkar, despite her irrelevance to the state’s history, illustrates this strategy. This can be contrasted with the state government’s ambivalence towards the NCERT’s recent Hindutva led revisions, although disfavouring the State’s own history which only exemplifies this attitude.

Bureaucracy: The Quiet Arm of Hegemony

It is within the bureaucracy is where the real engineering occurs. National studies confirm that Brahmins are heavily over-represented in senior IAS/IPS ranks despite being a demographic minority. Rajasthan has seen repeated controversies around promotions and selections, with Brahmin-Bania candidates favored over Rajput, SC, ST, and OBC aspirants. For instance, the chief secretary of Rajasthan, Sundhansh Pant and the Finance Secretary Vaibhav Galariya are both Brahmins. Further, nine of the 24 Officers deputed at the Chief Minister’s Office (CMO) are Brahmins — that is more than one-third. This pattern also reflects in appointments of Vice Chancellors & Judiciary. At Rajasthan University, 5 out of 8 Deans are Brahmins. Out of 32 government-run universities in Rajasthan, Brahmins were appointed as Vice-Chancellors in 11 — a striking overrepresentation for such a small demographic group.

Similarly, while several Brahmin and Bania officers currently serve as District Superintendents of Police, there is only one Rajput—and not a single Muslim—holding that position.

These administrative patterns influence which textbooks are printed, which religious boards receive funds, and which police cases are prioritised. The dominance of Brahmin officers ensures Hindutva’s agenda is implemented with sympathetic pro-Brahmin filters. For instance, both Sharma and Joshi (although no longer BJP State president but still highly influential) frequently attend events promoting Parshuram as a cultural icon — recently Sharma inaugurated a Parshuram Gyanpeeth.

Hence, institutional capture through selections ensures policy-shaping and policy enforcement in favour of the concerned castes — increased State funding towards the Vipra Boards, Vipra foundations, Brahmin-controlled Gyanpeeths, promotion of vegetarianism and selective application of cow protection laws highlight this policy-shift.

The Brahmin–Bania Axis

Recently, Shikhar Agrawal, the Additional Chief Secretary was given additional charge as chairman of RIICO. Rajasthan, particularly the Marwar region and Jaipur-Shekhawati belt, has been the traditional home of major capitalist Bania houses like the Birlas, Bajajs, Mittals, Godrejs, Jhunjhunwalas, Agrawals and Khatris. The Hindutva order in Rajasthan rests not only on Brahmin dominance in ideology and bureaucracy but also on the economic muscle of Bania corporates. Brahmins provide ideological legitimacy and administrative control; Banias provide capital, campaign financing, and media ownership.

Deregulation in mining, real estate, and energy overwhelmingly benefits Bania-controlled enterprises. Contracts in solar parks, cement, and infrastructure disproportionately go to groups like Adani, Birla, and Mittal. GST centralisation, championed by Bania networks has weakened smaller competitors while favouring large corporates.

The Adani Group’s explosive expansion into Rajasthan’s mines, solar projects, and logistics under BJP, the interests of the Birlas & Mittals in Cement, telecom, and education sectors safeguarded by policy, and Local Khatri & Mahajan networks thrive under SME-friendly reforms while enjoying bureaucratic protection, exemplify this. On the other hand, Rajasthani Muslims, historically strong in art, culture, handicrafts and local trade, are vilified to marginalise them economically. Similarly, ownership of farms and orans (grasslands) by small Rajput farmers and traditional heritage by Rajput elites is often attacked under the rhetoric of samantwad. Thus, while the state actively promotes the economic hegemonies of Brahmins, Banias, and Jats — and popular civil society discourse normalises these — the same socio-political channels stigmatise Muslim businesses and undermine Rajput property ownership.

In short, Brahmin–Bania synergy ensures that while Muslims are scapegoated and Rajputs are historically and politically side-lined, the real beneficiaries are the Brahmin-Bania elites who monopolise both state power and wealth.

Mechanisms of Social Engineering

This institutional capture and policy favouritism, is guarded by many strategies of social engineering like controlling information, culture, and using media and cinema to mislead public discourse.

The control of information and culture has played a pivotal role in social engineering.

Curricula and festivals are increasingly tilted towards Sanskritic, Brahminised traditions, side-lining Rajasthan’s syncretic and regional heritage. Similarly, Rajput-Muslim syncretic culture, exemplified by Sufi-Nathjogi traditions like that of Gogapir, are disfavoured for a more Brahmin-centric orthodox traditions like that of Parshuram. Similarly, Rajput-Dalit heterodox traditions of Ramdevji Tanwar and Rani Bhatiyani remain under constant attacks of Brahminisation by the State. This helps clear more space for Brahmin social influence over other communities — normalizing both institutional capture and policy favouritism.

However, what is more discomforting is the means and strategies employed to protect this hegemony, especially the social ramifications on the communities projected as social-punchbags for narrative decoys.

Muslims and Rajputs as the Mobilising “Other”

Unlike the Persian-origin Ashraf elites of Lucknow and Hyderabad — Rajasthani Muslims are either SC and ST convert or Rajput converts. While Kayamkhanis of Marwar & Bikaner, Sindhisipahis of Jaisalmer, and Khanzadas of Mewat are Muslim Rajputs, others like the Mirasis, Rangrezs, Langhas, Meos have been part of the traditional culture of the Hindu Rajputs.

Anti-Muslim mobilisation remained difficult in most pre-accession princely states due to the Muslim proximity to the Rajputs. However, that has dramatically changed in the last few years with various social engineering strategies, particularly Sanskritisation and Kshatriyaiaation. Hence, despite being local ethnic groups and despite being well-integrated contributors to the pre-accession Rajput States, including the modern armies — the Muslims are projected as the Turkic or Mughal “other.”

Furthermore, Muslim-othering has been followed by self-contradictory anti-Rajput rhetoric — the samantwad rhetoric by Brahmin and Jat politicians on one hand, and the violent conflicts over identity of medieval-era Rajput kings and other feudal lords on the other. The militant claims by Jats and Gujjars over Mihirbhoj Pratihar, Anangpal Tomar, Prithviraj Chauhan are not spontaneous social phenomena but politically-planned social engineering, termed “Rajputisation”. In this, different historical Rajput warriors and saints are assigned to different OBC communities to create social clashes between Rajputs and various OBC castes.

Hindutva’s obsessive appropriation of Maharana Pratap serves three key objectives. First, it eclipses the broader social, economic, and cultural contributions of Rajput dynasties, from the Pratiharas of Mandore onward. Second, it casts the rest of the Rajputs as collaborators with the Muslim ‘other.’ Third, it diverts attention from Hindutva’s ongoing project of Rajputisation.

Hence, BJP-RSS’s social engineering protects its policy of allotting more political space to Brahmins and economic space to Bania corporates. However, such social engineering is further compounded by narrative decoys (eg. Haldighati inscription debates) planted in media and films.

Discourse Deflection: Karauli Riots and the Afwaah Irony

During the run-up to the 2022 State elections, the State witnessed communal tensions and riots in Udaipur, Jodhpur and Karauli.

In Udaipur, the gruesome murder of Kanhaiyalal Sahoo was milked by BJP for anti-Muslim social-tension, while Karauli witnessed communal clashes triggered by rumours during a procession. Amid the fear, Madhulika Singh Jadaun, and her relative Sanjay Singh sheltered Muslims in her home and saved lives. Being the real heroes against Hindutva polarisation, they are reported to have said “This is Hindustan and we are Rajputs, we are known to protect people and we will always do it. Irrespective of faith,”

This irony deepens when we turn to the cultural sphere. Set in a Rajasthan town, Sudhir Mishra’s film Afwaah (2023), portrayed how rumours and political manipulation escalate into violence. However, both Madhulika, a garments seller, and Sanjay, a technician, are forgotten a year later. Instead, the film starring Bhumi Pednekar and Sumit Vyas, cleverly placed Rajputs at the centre of anti-Muslim violence.

Furthermore, the obsessive discourse around the change of the Rakt-talai inscription accompanied by a complete silence over Rajput protests against NCERT’s recent revisions fuels a misleading narrative that positions Rajput history as a beneficiary of Hindutva revisionism—a claim flatly contradicted by the recurrent protests Rajputs themselves have mounted against Hindutva’s distortions of their history in recent years — which can be read here, here, here & here.

The BJP-RSS machinery in Rajasthan has pursued Brahmin dominance with remarkable consistency, yet this reality remains conspicuously absent from most critiques of Hindutva in the state — deflecting discourse towards Rajput-Muslim history and the false binary instead.

Conclusion:

The real dangers of Hindutva lies not merely in the hate it spreads, but in the social order it entrenches: a system where Brahmins and Banias, wield an outsized supremacy over Rajasthan’s politics, economy, and culture — while constantly scapegoating the Muslims and the Rajputs through popular literature and cinema.

(The author is a mechanical engineer and an independent commentator on history and politics, with a particular focus on Rajasthan. His work explores the syncretic exchanges of India’s borderlands as well as contemporary debates on memory, identity and historiography; he can be contacted on adityakrishnadeora@gmail.com)

- https://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2025/Sep/03/rss-all-india-coordination-meet-in-jodhpur-from-sept-5-to-7

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/jaipur/ahilyabai-holkar-statue-unveiled-on-jmc-h-initiative/articleshow/121541829.cms

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are the author’s personal views, and do not necessarily represent the views of Sabrangindia.

Related:

PUCL slams recently passed Rajasthan anti-conversion bill as “draconian and unconstitutional”