The late scholar and historian, Dr. Bishambhar Nath Pande’s research efforts exploded myths on Aurangzeb’s rule. They also offer an excellent example of what history has to teach us if only we study it dispassionately

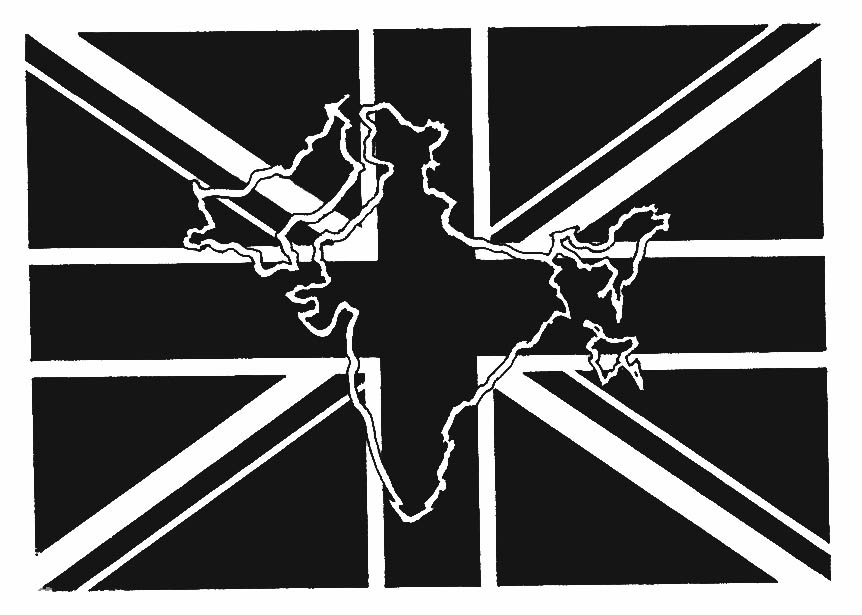

The Muslim rule in India lasted for almost 1,000 years. How come then, asked the British historian Sir Henry Elliot, that Hindus “had not left any account which could enable us to gauge the traumatic impact the Muslim conquest and rule had on them?” Since there was none, Elliot went on to produce his own eight–volume History of India from with contributions from British historians (1867). His history claimed Hindus were slain for disputing with ‘Muhammedans’, generally prohibited from worshipping and taking out religious processions, their idols were mutilated, their temples destroyed, they were forced into conversions and marriages, and were killed and massacred by drunk Muslim tyrants. Thus Sir Henry, and scores of other Empire scholars, went on to produce a synthetic Hindu versus Muslim history of India, and their lies became history.

However, the noted Indian scholar and historian, Dr Bishambhar Nath Pande, who passed away in New Delhi on June 1, 1998, ranked among the very few Indians and fewer still Hindu historians who tried to be a little careful when dealing with such history. He knew that this history was ‘originally compiled by European writers’ whose main objective was to produce a history that would serve their policy of divide and rule.

Lord Curzon (Governor General of India 1895–99 and Viceroy 1899–1904 (d.1925) was told by the Secretary of State for India, George Francis Hamilton, that they should “so plan the educational text books that the differences between community and community are further strengthened”.

Another Viceroy, Lord Dufferin (1884–88), was advised by the Secretary of State in London that the “division of religious feelings is greatly to our advantage”, and that he expected “some good as a result of your committee of inquiry on Indian education and on teaching material”.

“We have maintained our power in India by playing–off one part against the other”, the Secretary of State for India reminded yet another Viceroy, Lord Elgin (1862–63), “and we must continue to do so. Do all you can, therefore, to prevent all having a common feeling.”

In his famous Khuda Bakhsh Annual Lecture (1985) Dr Pande said: “Thus under a definite policy the Indian history text–books were so falsified and distorted as to give an impression that the medieval (i.e., Muslim) period of Indian history was full of atrocities committed by Muslim rulers on their Hindu subjects and the Hindus had to suffer terrible indignities under Muslim rule. And there were no common factors (between Hindus and Muslims) in social, political and economic life.”

Therefore, Dr. Pande was extra careful. Whenever he came across a ‘fact’ that looked odd to him, he would try to check and verify rather than adopt it uncritically.

He came across a history textbook taught in the Anglo–Bengali College, Allahabad, which claimed that “three thousand Brahmins had committed suicide as Tipu wanted to convert them forcibly into the fold of Islam”. The author was a very famous scholar, Dr Har Prashad Shastri, head of the department of Sanskrit at Calcutta University. (Tipu Sultan (1750–99), who ruled over the South Indian state of Mysore (1782–99), is one of the most heroic figures in Indian history. He died on the battlefield, fighting the British.)

Was it true? Dr Pande wrote immediately to the author and asked him for the source on which he had based this episode in his text–book. After several reminders, Dr Shastri replied that he had taken this information from the Mysore Gazetteer. So Dr. Pande requested the Mysore University vice–chancellor, Sir Brijendra Nath Seal, to verify for him Dr Shastri’s statement from the Gazetteer. Sir Brijendra referred his letter to Prof. Srikantia who was then working on a new edition of the Gazetteer.

Srikantia wrote to say that the Gazetteer mentioned no such incident and, as a historian himself, he was certain that nothing like this had taken place. Prof Srikantia added that both the prime minister and the commander–in–chief of Tipu Sultan were themselves Brahmins. He also enclosed a list of 136 Hindu temples which used to receive annual grants from the Sultan’s treasury.

‘When Aurangzeb came to know of this, he was very much enraged. He sent his senior officers to search for the Rani. Ultimately they found that statue of Ganesh (the elephant–headed god which was fixed in the wall was a moveable one. When the statue was moved, they saw a flight of stairs that led to the basement. To their horror they found the missing Rani dishonoured and crying deprived of all her ornaments. The basement was just beneath Lord Vishwanath’s seat.’

It transpired that Shastri had lifted this story from Colonel Miles’ History of Mysore which Miles claimed he had taken from a Persian manuscript in the personal library of Queen Victoria. When Dr. Pande checked further, he found that no such manuscript existed in Queen Victoria’s library. Yet Dr. Shastri’s book was being used as a high school history text–book in seven Indian states, Assam, Bengal, Bihar, Orissa, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh. So he sent his entire correspondence about the book to the vice–chancellor of Calcutta University, Sir Ashutosh Chaudhary. Sir Ashutosh promptly ordered Shashtri’s book out of the course. Yet years later, in 1972, Dr. Pande was surprised to discover the same suicide story was still being taught as ‘history’ in junior high schools in Uttar Pradesh. The lie had found currency as a fact of history.

The Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb (born 1618, reigned 1658–1707) is the most reviled of all Muslim rulers in India. He was supposed to be a great destroyer of temples and oppressor of Hindus, and a ‘fundamentalist’ too! As chairman of the Allahabad Municipality (1948–’53), Dr. Pande had to deal with a land dispute between two temple priests. One of them had filed in evidence some firmans (royal orders) to prove that Aurangzeb had, besides cash, gifted the land in question for the maintenance of his temple. Might they not be fake, Dr. Pande thought, in view of Aurangzeb’s fanatically anti–Hindu image? He showed them to his friend, Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru, a distinguished lawyer as well a great scholar of Arabic and Persian. He was also a Brahmin. Sapru examined the documents and declared they were genuine firmans issued by Aurangzeb.

For Dr. Pande this was a ‘new image of Aurangzeb’; so he wrote to the chief priests of the various important temples, all over the country, requesting photocopies of any firman issued by Aurangzeb that they may have in their possession. The response was overwhelming; he got firmans from several principal Hindu and Jain temples, even from Sikh Gurudwaras in northern India. These firmans, issued between 1659 and 1685, related to grant of jagir (large parcel of agricultural lands) to support regular maintenance of these places of worship.

Dr Pande’s research showed that Aurangzeb was as solicitous of the rights and welfare of his non–Muslim subjects as he was of his Muslim subjects. Hindu plaintiffs received full justice against their Muslims respondents and, if guilty, Muslims were given punishment as necessary.

One of the greatest charges against Aurangzeb is of the demolition of Vishwanath temple in Banaras (Varanasi). That was a fact, but Dr. Pande unravelled the reason for it. “While Aurangzeb was passing near Varanasi on his way to Bengal, the Hindu Rajas in his retinue requested that if the halt was made for a day, their Ranis may go to Varanasi, have a dip in the Ganges and pay their homage to Lord Vishwanath. Aurangzeb readily agreed.

“Army pickets were posted on the five mile route to Varanasi. The Ranis made journey on the palkis (palanquins). They took their dip in the Ganges and went to the Vishwanath temple to pay their homage. After offering puja (worship) all the Ranis returned except one, the Maharani of Kutch. A thorough search was made of the temple precincts but the Rani was to be found nowhere.

“When Aurangzeb came to know of this, he was very much enraged. He sent his senior officers to search for the Rani. Ultimately they found that statue of Ganesh (the elephant–headed god which was fixed in the wall was a moveable one. When the statue was moved, they saw a flight of stairs that led to the basement. To their horror they found the missing Rani dishonoured and crying deprived of all her ornaments. The basement was just beneath Lord Vishwanath’s seat.”

The Rajas demanded salutary action, and “Aurangzeb ordered that as the sacred precincts have been despoiled, Lord Vishwanath may be moved to some other place, the temple be razed to the ground and the Mahant (head priest) be arrested and punished”. (B. N. Pande, Islam and Indian Culture, Khuda Bakhsh Oriental Public Library, Patna, 1987).

Dr. Pande believed in the innate goodness of human nature. Despite all that senseless hate and periodical outbreak of anti–Muslim violence after independence, he remained an optimist. When one of the worst riots took place in 1969 in Ahmedabad, in which more than 2,000 Muslims were killed and 6,000 houses burnt, Dr. Pande travelled there to see whether there was “any humanity still alive”.

Yes, it was in one locality, Mewabhai Chaal, where he found that all the houses had been burnt down. Did they all belong to Muslims? No. Only 35 belonged to Muslims; some 125 belonged to Hindus, he was told. So, it meant, the arsonists came in two different waves; one destroying the Muslim houses and the other the Hindu houses? No, it was only one wave, said Kalyan Singh. That one, there, he pointed out to smoke billowing from what used to be his house and his tyre-shop. He was a Hindu and he had lost property and business worth 200,000 rupees.

The miscreants had asked him to point out the Muslim houses so they could spare the Hindu houses. Kalyan Singh refused, and watched as the mob set fire to all the houses – including his own. How could I betray my Muslim neighbours? he asked Dr. Pande rhetorically.

Dr. Pande also went to the Muslim students’ hostel. One–third of its residents were Hindus. “Come out all you Hindu students,” yelled a murderous mob gathered outside the hostel. No, we won’t, shouted back the Hindu students and locked the gate from inside. In the event, the entire hostel was evacuated by the army and then left to the mob to loot and burn. The Hindu students were told they could take with them their books and research papers. Dr. Pande met a young DSc scholar, named Desai, who had left behind his more than three years’ labour, a ready–for–typing dissertation, to be burnt by the arsonists. Desai said he couldn’t think of saving his thesis while some of his Muslim friends were in similar position with their theses. A noble soul! Dr. Pande who had been looking for humanity found it there as well.

The inhumanity did not lie in the Indian nature, but the nature had fallen victim to the evil heritage of colonial history. Few realised how 1,000 years of their history had been stolen from them. Many tended to buy the fake and doctored version handed down to them as part of their colonial heritage. Some even saw a little political advantage in this trade. Dr. Pande heard a leading Hindu Mahasabha politician and religious leader, Mahant Digvijaynath, telling an election meeting that it is written in the Qur’an that killing a Hindu was an act of goodness (thawab). Dr. Pande called upon the Mahant (High Priest) and told him that he had read the Qur’an a few ti mes but didn’t find such a statement in it, and he had, therefore, brought with him several English, Urdu and Hindi translations of the Qur’an; so would he kindly point to him where exactly did the statement occur in the Qur’an?

Isn’t it written there? said the Mahant. I haven’t found it; if you have, please tell me, replied Dr. Pande. Then what does it say? It speaks about love and brotherhood, about the oneness of mankind.

What’s jihad then? What is jizyah? How then India got partitioned? The Mahant went on asking, and Dr. Pande kept on explaining, hoping the Mahant would correct himself.

However, the Mahant’s ideas were fixed, in prejudice and in ignorance. Dr. Pande himself had been a senior member of the ruling Congress party which he had joined at a very young age. He was a disciple of Gandhi, a friend of Nehru; he had taken part in each and every non–cooperation movement against the British and gone to jail eight times. The Congress was supposed to be an all–Indian nationalist platform and yet Dr. Pande’s party was hardly free from the bias and ignorance of a cleverly deconstructed history. The rise of militant Hindutva tendency is only recent, but before it all became overt, the Congress itself was doing the same, albeit a little covertly. All the horrific anti–Muslim carnage took place during more than four decades of Congress rule. The doors of the Babri Mosque were opened for Hindu worship during the tenure of Nehru’s grandson, Rajiv Gandhi. The Mosque itself was pulled down during the regime of another Congress Prime Minister, P. V. Narasimha Rao.

Dr. Pande was, however, just one individual. That made his work all the more important, not just from the Muslim but from the point of view of the entire country. India’s deconstructed history is like a time bomb; unless it is defused, India cannot survive in one piece. Not for very long.

(Bishambhar Nath Pande born on 23 December 1906 in Madhya Pradesh of Umreth; member UP Legislative Assembly (1952–53); member UP Legislative Council (1972–74); twice member of the Rajya Sabha (1976 and 1982); governor of Orissa state (1983–88); recipient of Padma Shri (1976); author of several books, including The Spirit of India and The Concise History of Congress; died in New Delhi on June 1, 1998).

(Courtesy: Impact International, London, Vol 28, July 1998).

Archived from Communalism Combat, October 1999, Anniversary Issue (6th) Year 7 No. 52, Cover Story 8